Samuel Morse: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

Despite his 1835 appointment as a professor of art at New York University, Morse spent much of his time tinkering with the telegraph. Morse raised enough money to apply for a patent in 1837 and to improve the telegraph. He got European patents for the telegraph. Eight years later he convinced Congress to appropriate money for an outdoor test line between Baltimore, Maryland and Washington, D.C. The first official telegraph message was, “What hath God wrought.” The telegraph quickly became more than a toy—the Baltimore test line was used in 1844 to send news of Henry Clay’s nomination for president from the National Whig Convention in Baltimore to Washington, D.C. | Despite his 1835 appointment as a professor of art at New York University, Morse spent much of his time tinkering with the telegraph. Morse raised enough money to apply for a patent in 1837 and to improve the telegraph. He got European patents for the telegraph. Eight years later he convinced Congress to appropriate money for an outdoor test line between Baltimore, Maryland and Washington, D.C. The first official telegraph message was, “What hath God wrought.” The telegraph quickly became more than a toy—the Baltimore test line was used in 1844 to send news of Henry Clay’s nomination for president from the National Whig Convention in Baltimore to Washington, D.C. | ||

Morse immediately organized the Magnetic Telegraph Company. At age 56 he had finally found fame and financial security. He remarried and moved into a new home equipped with a private wire hooked into a telegraph line. He was able to communicate instantly with friends all over the country and even all over the world after the first transatlantic cable lines were laid during the 1860s. Morse’s basic telegraph design was in use until after his death in 1872, and the Morse Code remained the standard well into the 20th century. | [[Image:Morse_telegraph_register_0442.jpg|thumb|left|Morse Telegraph register]]Morse immediately organized the Magnetic Telegraph Company. At age 56 he had finally found fame and financial security. He remarried and moved into a new home equipped with a private wire hooked into a telegraph line. He was able to communicate instantly with friends all over the country and even all over the world after the first transatlantic cable lines were laid during the 1860s. Morse’s basic telegraph design was in use until after his death in 1872, and the Morse Code remained the standard well into the 20th century. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

[[Category:People_and_organizations]] [[Category:Inventors]] [[Category:Communications]] [[Category:Telegraphy]] [[Category:Electrical_telegraphy]] | [[Category:People_and_organizations]] [[Category:Inventors]] [[Category:Communications]] [[Category:Telegraphy]] [[Category:Electrical_telegraphy]] [[Category:Morse_telegraphs]] | ||

[[Category:Morse_telegraphs]] | |||

Revision as of 17:59, 17 November 2008

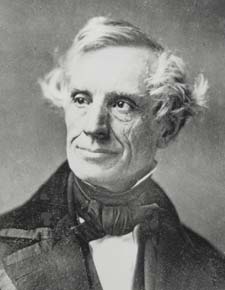

Samuel Morse: Biography

Born: 27 April 1791

Died: 02 April 1872

Samuel Finley Breese Morse, artist and inventor, was born to Jedediah and Elizabeth Morse in Massachusetts in 1791. Though he was an art major at Yale University, he also studied chemistry, natural philosophy, and electricity. Dreaming of becoming a great painter, he then studied art at the Royal Academy in London. The only problem was that Morse wished he could talk to his family across the sea.

After returning to the United States Morse had trouble making a living as an artist. He tried inventing, but didn’t make much money at that either. By the mid-1820s he was faring well as a portrait painter, but he was frustrated by the amount of time he had to be away from home while working on the portraits. Morse continued trying to invent things so he could make enough money to stay home with his wife and children. Although his machine for carving marble made some money, he still had to travel a great deal and was not at home when his wife died. He didn’t even find out about his wife’s death until the day after her funeral. After that, he was determined to find a way to speed up communications.

In 1829 Morse returned to Europe as an artist. On the ship back to the United States in 1832, he joined a group of passengers discussing the growing field of electricity. A fellow traveler pointed out that electricity could pass almost instantly through any length of wire. Morse was convinced of the possibility of transmitting words this way and became obsessed with the idea of the electrical telegraph. He also came up with a system for this communication, realizing that if a current of electricity passing along a wire was interrupted a spark would appear. Sparks, their absence, and the length of time between sparks could be combined into an alphabet of signs of dots, dashes, and spaces that could be used to record words transmitted over wire. This system later became known as Morse Code.

Despite his 1835 appointment as a professor of art at New York University, Morse spent much of his time tinkering with the telegraph. Morse raised enough money to apply for a patent in 1837 and to improve the telegraph. He got European patents for the telegraph. Eight years later he convinced Congress to appropriate money for an outdoor test line between Baltimore, Maryland and Washington, D.C. The first official telegraph message was, “What hath God wrought.” The telegraph quickly became more than a toy—the Baltimore test line was used in 1844 to send news of Henry Clay’s nomination for president from the National Whig Convention in Baltimore to Washington, D.C.

Morse immediately organized the Magnetic Telegraph Company. At age 56 he had finally found fame and financial security. He remarried and moved into a new home equipped with a private wire hooked into a telegraph line. He was able to communicate instantly with friends all over the country and even all over the world after the first transatlantic cable lines were laid during the 1860s. Morse’s basic telegraph design was in use until after his death in 1872, and the Morse Code remained the standard well into the 20th century.