Oral-History:Thomas Bartlett

About Thomas Bartlett

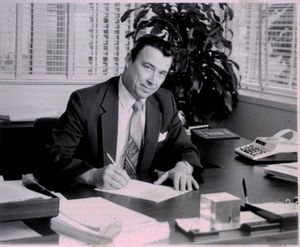

Thomas Bartlett was born August 30, 1928 in Brooklyn, New York. After taking low-level jobs at the AIEE, he studied accounting at night school and was elevated to an accounting position. From there, he rose to the head of accounting operations at AIEE and stayed on with the IEEE after the merger of the AIEE and IRE in 1963.

In the interview, Bartlett discusses his childhood, early career at AIEE, and short stint in the military during the Korean war. After returning to the AIEE and re-educating himself in night school, Bartlett gradually attained a management position. He discusses the technological and organizational changes in the AIEE/IEEE over the last several decades, focusing on computer technology. He also discusses the personalities and leadership of several IEEE officers. The interview concludes with his comments on the way revenue generation at IEEE has gotten more aggressive in recent years.

About the Interview

THOMAS BARTLETT: An Interview Conducted by William Aspray and Loren Butler, Center for the History of Electrical Engineers, June 3, 1993 and June 17, 1993

Interview # 161 for the IEEE History Center, The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.

Copyright Statement

This manuscript is being made available for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the IEEE History Center. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of IEEE History Center.

Request for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the IEEE History Center Oral History Program, 39 Union Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901-8538 USA. It should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

Thomas Bartlett, an oral history conducted in 1993 by William Aspray and Loren Butler, IEEE History Center, New Brunswick, NJ, USA.

Interview: Part One

INTERVIEW: Thomas Bartlett INTERVIEWED BY: William Aspray and Loren Butler PLACE: IEEE Offices, Piscataway, New Jersey DATE: June 3, 1993

Childhood and Education

Aspray:

Please begin by telling me when and where you were born and what your parents did?

Bartlett:

I was born on August 30, 1928 in Peck's Memorial Hospital in Brooklyn, New York. My father was born in Bareneed, Newfoundland and spent his earlier years as a fisherman on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, and also worked the iron mines, until he was almost 18. He had one experience that significantly affected him. He was leaning against the railing of a mine shaft, the railing cracked, and he fell down. The shaft was about 200 feet deep. Fortunately, he fell only about 15 feet and landed on top of a car that was coming up. So as a result, I'm here. [Laughter] He decided that he no longer wanted that kind of a life, so he came to the United States and entered the printing business. He worked for Scribner's and Sons, which is a publishing house, where he was a stone-hand. A stone-hand in those days was the individual who locks up and makes ready the plates before they go onto the presses. This was before the new technology.

Aspray:

What about your mother?

Bartlett:

Mother worked in the Brooklyn Navy Yard as a secretary. She stopped working when she was married. She was born in Brooklyn. She had three sisters and one brother. And my father had three sisters.

Aspray:

And were there brothers and sisters of yours?

Bartlett:

I have only one sister, Muriel, who was a registered nurse. During World War II she served on Tinian, and she was there when they had the atom bomb on Saipan, from where they took off to bomb Japan. She has a certificate documenting this, as did all the people on the Marianas. When she came back from the service, she married Donald Muller. They live in Iowa, and are now both retired. Her husband traveled to many schools in Iowa training people how to work with children who have Downs Syndrome and other learning disabilities.

Aspray:

Tell me about your childhood. Did you have hobbies? Were you an outdoors type? Did you read a lot? What sorts of things did you do?

Bartlett:

Very outdoors type. In fact, my mother would say I would eat, sleep, and get a clean shirt, and that's about the only time she would see me. I loved the outdoor life. I was very athletic in sports — in all kinds of sports. Every season I was into a different sport. I loved swimming, track, baseball and football. Never played any hockey, but I loved the sport. Stick ball was a big thing among kids in those days. It was a very exciting period of time for me.

Aspray:

Did you have hobbies such as ham radio or science projects?

Bartlett:

No. Probably my only hobby was music and stamp collecting. I had quite a stamp collection and still do. My wife, Elaine, and I were married December 10, 1949, and we have two sons. Our oldest boy, Scott, is an electrical engineer who works for Grumman Aerospace. Our younger son, Glenn, is an electronic technician currently. He is still going to college nights for his degree in computer science. It's kind of interesting that they went into the electronics field, though I'm not an engineer. I'm an accountant by profession. They just seemed to gravitate into that area. Perhaps I had something to do with it because I felt that engineering training was good. No matter where they went in life, I felt that the training that you receive in your education as an engineer you could apply almost to anything.

Aspray:

Tell me about your own formal education. How were you as a student?

Bartlett:

Very good in public school. In fact, I skipped, which is something they don't do anymore. I skipped class 3A, so I went from 2B to 3B. Because my grades were very good. I'm not sure if that was a good idea because that advanced me into a different physical group of people. I was always at a disadvantage. I was always very short. Maybe that's why I was aggressive in sports. I graduated from high school as the shortest kid in my class at a roaring 5'2", and one year later I was 5'10-3/4". [Laughter] My mother said she could just see me growing out of my pants every week. [Laughter]

Aspray:

What school did you go to?

Bartlett:

In high school I wanted to go into aviation. I loved aviation, and I always had. So I went to a vocational school. I took the test for Brooklyn Poly and passed it. But a grade advisor said, "Why don't you go to Woodrow Wilson because it's a brand new school, and they're going to have all of the special aviation courses." So I listened to that grade adviser and made the mistake of my life because Woodrow Wilson was not a good school for what I wanted, and I missed the opportunity of going to Brooklyn Tech, which was much better. I eventually went into the Navy Air Reserve and was stationed down at Floyd Bennett Naval Air Station, where we would do weekend duty. I did this because I wanted to get close to aviation, but it turned out that I have a punctured eardrum and could not get into flying. In fact when the squadron that I was in was activated during the Korean War, they told me, "You never should have gotten into the reserves with the ears that you have." I had chronic mastoids as a child, and I guess it created a problem. But they added, "You've been trained, so you're in." [Laughter]

Finding Employment at AIEE

Aspray:

You graduated from high school in what year?

Bartlett:

I graduated from high school in 1946 at the end of January, and I started at AIEE, on February 11, 1946. As the story goes — and it's a true story — I had two job interviews to go to that day. They were both near the subway at Fortieth Street and Sixth Avenue in Manhattan, one to the left and the other to the right. The red light was against me, so I said, "Well, I'm not going to wait for the red light, so I'll go to the other interview at Thirty-ninth Street," and I walked into the Engineering Society's Building. That's where it used to be, on Thirty-ninth Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues. The building is still there, by the way. It was the most gorgeous thing, at my age, that I had ever seen inside — all marble columns, a marble floor. I just said, "Boy, I would like to work here." And I was fortunate enough that I was hired. I started work almost immediately.

Aspray:

How did you find out about this as an opportunity in the first place?

Bartlett:

A newspaper ad in the local paper. Just before I graduated I started looking for jobs. I had no practical training at that time because, going to a vocational high school, the only kind of practical training was some kind of shop work. Such as a machine shop, woodworking or printing, which I did not want to do. Those are the trades I learned. I had gone to Woodrow Wilson to get into a pre-flight courses, trying to learn basics to get into aviation, and that was all wiped out. I didn't know what I wanted to do, so I said, "Well, I'll just get an office job as an office boy in a shipping department, and figure out what I'm going to do." So I started in the shipping department at AIEE. I was working with some great people. The person that did the original interview, Floyd A. Norris, was one of the most outstanding individuals I've ever had the pleasure of working for. He was very articulate; he was very immaculate in the work that he did. He was the office manager, and he also maintained all of the financial accounting records. The precision that he worked with, and the style that he worked with, set a pattern for my business career. I was also very fortunate that I worked directly with an individual by the name of Warren Braun. Warren was at that time the shipping manager, but he ultimately moved far up the ranks. At the time of the merger, he had a position something like associate office manager.

Aspray:

Before you go on, let me ask a couple more questions about your job search. In 1946 people were coming back from the war. It must have been hard to get jobs at the time, is that right?

Bartlett:

Not at the entry-level that I was seeking. I started at $26 a week, and there were not many fellows coming back out of the service, who were married or had plans of getting married, that wanted to start for that salary.

Aspray:

Do you remember anything at all about the advertisement? What attracted you to that particular one? Were you interested in working for a place that was an engineering group? Or did you really know what it was all about?

Bartlett:

I really didn't know what it was all about. It was just an open type of an ad. I don't recall the ad exactly. Something like "professional organization," I think that's what it said. It didn't say an engineering society or anything like that. Just "work for a professional organization, steady employment, no travel." [Laughter] And that caught my eye. I said, "well, you've got to start somewhere in this whole thing."

AIEE Organization and Culture in 1940s

Aspray:

How large was AIEE when you joined them?

Bartlett:

We had 25,000 members. I just looked up some of the statistics. I was curious to see. The total assets of the organization were just over a million dollars. The expenses were something like $600,000 a year. Today we're $121 million a year and 320,000 members. At that time there were 75 sections, and today we have almost 300 sections.

Aspray:

What was the staff size then?

Bartlett:

As well as I can recall, the staff size was about forty. Let me go back to another statistic. One of the items that I found to be extremely interesting was that in 1946 we published 1,486 pages. In 1992 we published 264,000 pages. And that, to me, is what the organization is all about, the dissemination of technical information. That shows how we've really grown. I was fortunate, I think, that I came to the Institute, fortunate that I've met some people that I would never have had the opportunity of meeting or getting to know. It's just been a real challenge and a wonderful experience.

Aspray:

I'll come back and ask some questions about personalities later. Let me first ask you about the AIEE staff and its organization at that time you came.

Bartlett:

When I started in the mail room, I was the only young man. Warren Braun was the other person. He was in charge of the mail room, and he and I worked together as a team. There was a room next to the mail room, which was the addressograph room. A fellow by the name of Edward Ege was in charge of the addressograph machine, which was how you maintained the addresses. They were on metal plates, and you could put little tabs in to indicate what publication a member was entitled to. Ege had Betty Peterson working for him. We worked together almost as a team, so I got to learn how to use the addressograph machine and worked with Warren on handling of orders. When I came to work for the first time, on February 11th, it was just about at the height of the Winter General Meeting, which was like the Power Engineering Society meeting of today. They had preprints, the same as they have today — individual pamphlets. For about six weeks, after our regular day we'd work from five o'clock until eleven o'clock at night. So the day started at eight in the morning, and we worked until eleven at night. For those extra hours there was no overtime paid, no straight time. We got a dollar and a half supper money. After the first week of doing this, Mr. Norris called me in and said that Warren was very pleased with my work, and that I was getting an increase from $26 to $28 a week. [Laughter] So I worked one week and got a two-dollar raise. I mean, that was unreal, kind of great.

About two weeks after that, something else happened that I will never forget: It was about three o'clock in the morning, and my mother heard me. I was in the hall upstairs in the bedroom area. She walked up to me and said, "Tom, what are you doing?" I was holding two of her best Irish linen towels in my hand. I was sound asleep and said, "I'm looking for an envelope. I've got to mail these out for Warren." [Laughter] So those are the little things that come back to you over the years, and they're really funny.

Aspray:

If you look at the organization then, what kinds of departments were there, and how did it compare with today?

Bartlett:

We had a membership department similar to what we have today. There were four people, as I recall, in the membership department. There were two people in the cash-processing department. Mr. Norris had his secretary: Peg Cashen, later Mrs. Coffey. There was the publications staff, and a technical activities department. There was only one publication, which was Electrical Engineering. That was our core publication. The editorial staff ultimately moved out of the engineering center, because we ran out of space, and moved to 500 Fifth Avenue, which was on the corner of Forty-second and Fifth Avenue. One of the chores which we had to do everyday was to take the mail from Thirty-ninth Street to Forty-second Street and also make our deposits in the First National Bank, which also was at Forty-second Street. Very similar to what the young fellows are doing today. I'm very sympathetic to those guys, because I know what they're going through.

Aspray:

Was there a standards operation at that time?

Bartlett:

Yes, there was a standards activity. When I joined AIEE, a Mr. Farrer was in charge of standards. Later, Mr. John Anderson, who worked in the department, was placed in charge of standards activities. John has retired and is living in Connecticut now. In technical activities, there was an Ed Day and a Reginald Gardner and Charles Rich, who was then the editor for Electrical Engineering.

Aspray:

One question that historians ask these days is about so-called "corporate culture." What was it like to work there? Was there a family orientation or a business orientation?

Bartlett:

It was a real family-type of an activity. Everybody was close, partly because it was a relatively small staff. The editorial department was removed from the rest of us. Historically, that always seems to be the way it is with the editorial part of the office. They seem to gravitate to their own area, their own type of people. They stay outside the regular operating staff. The membership department, the mail room, the cash-processing, they all worked very closely together, got to know each other very well, and got to be very friendly with each other. There was not a great deal of socializing as such outside the office. But within the office it was a very close, tight family.

Aspray:

Did the organization have parties, outings, things like that?

Bartlett:

No, nothing like that at all. They had no clubs. We always had the annual Christmas party, and that was the only activity that I would say was outside of the norm.

Aspray:

Most people lived in the city?

Bartlett:

Yes. By and large, almost everyone really came from either close in New Jersey, a few from Westchester, or from the five boroughs. I don't recall if anybody came from Nassau County. But most everybody lived pretty close to the city.

Aspray:

When you were there, did that building house some of the other professional engineering societies?

Bartlett:

Yes, it did. The civil engineers, the mechanical engineers, the mining engineers, and several other societies. We also had in the building in those early years, the Society of Automotive Engineers, but they ultimately moved out and went to Warrendale, Pennsylvania — near Pittsburgh. They have their own building there. But the five founder societies have stayed together all the years. The UEC was created by the founder societies. The founder societies put their individual libraries together under the consolidated Engineering Societies' Library. That was also located in the building. They had a beautiful auditorium in the United Engineering Center on Thirty-ninth Street, and it had a balcony. The acoustics in that particular theater were so good that it was used for recordings. Benny Goodman used to come and practice and record in the building. We'd sneak down, [Laughter] and sit in the balcony and listen to Benny Goodman record. With other fellows from the other societies who were in the shipping department, we were a kind of clique.

Korean War

Bartlett:

I was in the shipping department from 1946 until I got married in 1949. A year later, in 1950, the Korean War broke out. My squadron was activated, and I was called to active duty. I was fortunate in that I was transferred to Chincoteague, Virginia. There was an experimental squadron there, VX-2. What they were doing was developing the radar gun sight on that particular base. I was in ordnance, and my job was to clean the guns, maintain all of the ammunition and do related activities. Being in Virginia was fortunate because I could drive back and forth on weekends to see my wife. We would drive up from Virginia on Friday night at five o'clock and come barreling into New York at about eleven o'clock. You had no bridge between New Jersey and Delaware, you had no New Jersey Turnpike. You had to come across on a ferry to get there. Saturday night would be a normal sleep night for us, Sunday night we would meet at about twelve-thirty in Manhattan.

I would round the guys up at a local bar and pile them into the car. Because I was married and sober and they were all single I would pile them into the car and drive them back to the base. I would drive right through the night. It would get us to the base at about five-thirty, quarter to six, and we would change our clothes. I would always draw the Monday night watch from twelve to four from somebody else, so that I could get the next weekend off. Some of the guys didn't care. They hated the watches. They didn't mind staying on the base during the weekends because it was kind of easy duty on weekends. I would always grab the twelve to four so that I could go home on the weekends. Thus I didn't get any sleep from Saturday night to Tuesday night. It fit into my lifestyle in the sense that I'm fortunate that I can get by with just a very, very few hours of sleep at night. Living where I do today, out on Long Island, I leave my house at four in the morning, get to the office at six, and I usually get to bed at eleven-thirty, twelve o'clock at night. So I'm getting about three and a half hours sleep a night. I'm fortunate to survive that way with no problem.

Return to AIEE and Pace

Bartlett:

After 1952, when I came back, I spoke to Mr. Norris and explained that since I was married, I didn't want to go back into the mail room; that I wanted the opportunity of getting into accounting work. He encouraged me to do it. I went to Pace College at night. He allowed me to transfer into what was the bookkeeping department because we didn't have an accounting department per se in the organization. He did all that work. I went to Pace College for eight years at night to get my degree, worked during the daytime, and worked my way up. I was made chief accountant around 1961 or 1962, just prior to the merger. When the two societies merged in 1963, that was kind of a traumatic year for everybody. You had two organizations and everything was duplicated, and you knew that half of us were not going to survive in time. No matter how they promised that everybody would be protected, you knew that no organization could survive with two people in every job.

Aspray:

Right.

Bartlett:

There were personal conflicts between the departments. People were not willing to share information or ideas. They would work together as individual cliques. It was a tough time.

Aspray:

Let's go back and briefly cover that period where you were just the accountant at AIEE before we go on to the merger. How was it that you got interested in accounting rather than some other aspect of the business?

Bartlett:

I'd have to say that it was Floyd Norris, who made that much of an impression on me: his work ethic, his mannerisms. He just impressed me as an individual person. I wanted to emulate him. Since I couldn't get into aviation, and I knew I was going to have to be in business, I felt that, if you're going to be in business, accounting is a basis that you have to have. It's either going to be that or law or something along those lines — and accounting was what I chose. I had always been reasonably good at math. I enjoy working with numbers. So that's how I got there.

Aspray:

You went back to school at nights to Pace. Was it strictly required in order to hold that kind of job? Or did you feel that you just needed that background?

Bartlett:

You had to have a degree in accounting in order to do the work and to carry out the responsibilities. It would be like trying to be an engineer without an engineering degree. Some people can do it and get away with it. But you need to know some things about law. You certainly need to know the basis of accounting. You have to know what the rules and requirements of accounting are in order to maintain your financial records to meet the accounting standards. And as accountants, we are subject to review just like any other profession. When we produce a financial statement, that statement has to be maintained in accordance with the Financial Accounting Standards Board.

Aspray:

Would you say that the education you received was one that prepared you well for doing your job at IEEE?

Bartlett:

Oh, yes. I inquired and found that Pace was probably the best university or college in the New York area at that time to give you the training in accounting. It was really a business-type college. They didn't have the necessary number of degree programs to allow them to become a university at that time. They have since grown to be quite a university in the New York area. They have a campus in Westchester as well. And they're still recognized as one of the outstanding schools in the country in accounting and business training. So I was fortunate.

Office Technology in 1950s

Aspray:

How about practices at AIEE? Were things done in a professional manner? Was there something different about the way it was done then as compared to now?

Bartlett:

It was certainly done in a very professional manner, but everything was manual. We did not have any automated equipment. Typewriters in those days were the extent of office automation. Even adding machines were not anything like what you think of today. One of the major breakthroughs was when we purchased a Monroe calculator that worked manually. If you wanted to multiply numbers, you multiplied by individual rows. You had to turn a crank to move to the next row of numbers and multiply times that, and turn the crank again, and so on down the digits. We were really manual. It was a person's writing neatness that had a great deal to do with the ability to read the financial records.

When we sent out the dues bills in those early years, all of the dues bills were printed on the addressograph machine. Based upon the grade of a member, a certain tab would be in the addressograph to determine what his grade was. A bill was printed for that grade. Then the entire staff worked together, and we would sort all the bills into strict member number order. The member records were in strict numerical order, maintained in large ledgers with about forty names on a ledger. You took a date stamp and your pen, and you'd put a date next to the name as to the year of the dues, and you'd write in the amount of the dues that was being charged. Then the bills would all be sent out. When the second notice went out, you went through the same thing, except that you then had to match the bill against the ledger to see if this individual had paid, and if he had, you threw the bill away. [Laughter] We had to go through them all, sort them all and throw many of them away. The third notice was the same thing, and the fourth notice was the same thing. When the payments came back, you had to sort them into numerical order. The women in the office would type pages of the member number, name, and the dollar amount paid. The cash department had the responsibility of making certain that each page reconciled with the amount of cash received. We then had to take those pages, go through the ledgers, and enter the date when the member paid and the amount of money paid.

That was the extent of our accounting system for dues. All of the payments for publications and products were manually entered in columnar-type records. I guess the first change came when we began to get calculators that were electric. I remember the first ten-digit calculator that we bought. It was so fast, but cost about $400.. That was a lot of money at that time. All it did was add, subtract, multiply, and divide. There was no floating decimals or anything like that. It was just the basics.

Aspray:

The original ones had ten numbers for each digit.

Bartlett:

Absolutely. All rows, all columns. So you had to enter the numbers in their respective rows. Once the ten-digit machines came available, you could look at a column of figures, without looking at the different keys. It's just like a typist. You got the touch and the feel. That certainly speeded work up. I guess that was probably around 1950 or 1951. George Hermann, who replaced Mr. Norris as office manager when he retired, wanted to automate things. He intensified the search for automated-type equipment. We moved into a heat-transfer, punched-card system, whereby the individual's name was typed on a card that also had punches in it. Through a heat-transfer process, you could transfer a member's name and address to a mailing label and yet still use the card for sorting purposes.

Aspray:

I see.

Bartlett:

You were able to generate a lot more information this way compared with using the old tabs. It turned out that Eddie Ege also retired, so the time became right for these changes to be made. I really got in on the ground floor of all of this type of work. We then progressed into machine accounting, whereby we would do our own programming. Programming in those days was done by wires. You would take a wire from one location and plug it into a pinhole in another location of this board. That was the basis of how you would generate reports. One area would have a numerical field for the membership number, and there were other financial information sections. Once you got this wired — and there were literally hundreds of wires on every one of these boards — you'd put a cover over the whole thing and lock it. You didn't want anyone to start pulling those wires out.

Aspray:

Was the amount of information that had to be tracked, especially for, say, the government, or for auditing purposes, less than it is today?

Bartlett:

Much less. As with everything else, as you are able to do more, people want more. The result is you became able to track more information, government reports became more difficult, more voluminous, and more detailed. The same thing happened within the organization. The Board began to look for more detailed information. The financial reports that used to come out in the earlier years were very simplified accounting reports. Amounts were given in pennies. Financial reports later on dropped the pennies and just entered dollars. Now we report in thousands of dollars and merely show a decimal point. Things change because it's the order of magnitude of a number that becomes important to management. The old story is that no number should be more than three or four digits because it becomes difficult to interpret and to recognize a value if there are more than that. The situation with financial reports was typical.

Job Mobility

Aspray:

Did people remain at AIEE for long periods of time? Was it the sort of place that you'd begin your career and continue to work there?

Bartlett:

I almost have to feel that in those days all organizations were like that.

Aspray:

Really?

Bartlett:

In those days, once you got a job in a company, you became almost locked into that company. With the exception of a few areas, such as sales and advertising where you would gravitate to different companies. The people that I knew, when they joined a company, stayed with that company for twenty or thirty years. It was just the lifestyle. Today, there is much more mobility of people from company to company. It's a way of progressing through your professional career — by making these changes. I was fortunate to have that professional growth capability within the AIEE and the IEEE. Not all organizations have that. If you join a big company in the accounting department, you may get into the accounts receivable department A through C, and that's where you are locked into, and you stay there. You may progress to D to F or something. With a small organization you get to do everything, and you really did. It was great. You helped out in the membership department, you helped out in the addressograph, you helped out in the cash department, wherever they needed the help.

Growth and Management of AIEE

Aspray:

Was AIEE a fairly stable-sized organization, or was it still growing at this time?

Bartlett:

We were still growing. It was not a rapid or dynamic growth. In 1946 we had 25,000 members. And as I recall, by 1963 we had grown to about 60,000. So there was growth. It was a steady growth. But it was primarily in the power engineering field. As that particular field was growing, we grew. They later brought out three new publications besides Electrical Engineering: Communications & Electronics, Applications in Industry, and Power Apparatus & Systems. They seemed to offer to the members a diversity of something outside the magazine Electrical Engineering. So there were changes that were taking place, but nothing like what took place within the IRE, where they had the group structure. That was very broad-based, and it brought in many members. IRE was a much more dynamically growing organization. Many years prior, IRE had been a part of AIEE, and they splintered off and went their own way. So it's kind of interesting that they then came back again, later on.

Aspray:

I suppose that with AIEE growing, the staff also grew a little bit, so that there were more opportunities for progressing through the ranks, rather than if you stayed the same size.

Bartlett:

That's exactly right. Mr. Norris used to do all the accounting work in the earlier years, and then later on he transferred more and more of that to my responsibility as he took on more management-type responsibilities. But he was always there looking over my shoulder, guiding me. I can never say enough about this particular individual because his code of ethics was just so exacting. This is a man who would never steal a penny from anyone. If he found something, he would go out of his way to try to find out who the owner of it was. Very high morals. He set a tone for the entire staff. He was very, very well respected. I was also fortunate to have Warren Braun, who to me was like a second father. He took me under his wing and taught me all the basics of work in addition to the technical knowledge that I got from Mr. Norris. This was more of just a general business type of thing. How to do things with your hands in business.

Aspray:

Who held the position that's equivalent to the General Manager now?

Bartlett:

That would have been Henry Harrison Henline. The title at that time was Secretary. After he retired, Nelson Hibshman became the Executive Secretary. Then at the time of the merger; Nelson retired and Don Fink was elected to that position.

Aspray:

What can you tell me about these people — as people or as managers? Can you put some personality onto these people so we can know what they're like?

Bartlett:

Well, Warren to me was like a second father. He was always there for me whenever I needed any help or assistance in how to do something. He was extremely well respected by everyone else on the staff. But he was more than just respected; he was liked by everybody. I've never heard a single person say a word against him. He'd always be there for everybody, always willing to work long hours to get things done. You didn't think to ask if you were being paid for this. It was a job to be done, and you went about and did it. You didn't ask, "Is that in my job structure? Is that in my responsibility?" Everybody worked as a group together. Oh, there were a couple of people — I won't even mention their names, but you get them in any organization — who are the annoyances that you have to put up with in life, unfortunately. But there were very few of them.

Mrs. Landres, who was in charge of the membership department at that time, was a very gentle, personable woman. She was always proud of her family. I felt very bad because she had worked all of her life for the benefit of her children, and planned that she and her husband were going to travel around the world when they retired. Both she and her husband retired on the same day, he in a different company. And at his retirement party he had a heart attack and died. So they never went, never made the trip. It was a terrible, sad time in the office. The response was typical, though. When something happened, everyone got together, and everyone would help in any way that they could. They do it here, too. People attend funerals and the services, and try to extend themselves. But here it's a department usually. Whereas there it was the entire office. It was a very close-knit type of thing. Everyone had very high morals. You didn't have anything like things that happen today — fortunately, only outside this office. We have never seen it here. But you hear of stories that go on in other companies.

Aspray:

Did you get to know the Secretary?

Bartlett:

Not too well. The Secretary would relate mostly to the General Manager. I got to know Mr. Henline, but not to a great degree. It would be a courtesy "Good morning." He would say "Hello" and things like that. But when Mr. Hibshman was Secretary, he was much more open with the staff. He was much more of a friend to the staff. He worked together to help lead people, and he would interact between the Board and the staff whenever he felt it was necessary to act as a buffer. If something went wrong, he would be the one who would stand up and take the problems on as his responsibility, not somebody else on the staff. That created a great deal of affection for him, and respect, that he was willing to do that. He would pass accolades back to the staff when things went well, but he was the buffer when things did not go well.

Aspray:

You are intimately familiar with volunteer organizations and the advantages but also the disadvantages of staff working in such an organization. Were they similar then to the way they are now?

Bartlett:

It's hard for me to say because it's only in my more senior years that I have had the interface with the volunteers. Certainly in those earlier years I didn't have a great deal of interface. I would, however, meet the Treasurer on a periodic basis. In those days all checks that were over $5,000 had to be signed by the Treasurer of the organization.

Aspray:

Who was a volunteer?

Bartlett:

Yes, a volunteer. The individual that I originally had to meet with was Professor Schlichter, who was at Columbia University. One of my chores was to take all checks that were over $5,000 to Columbia University and get Professor Schlichter to sign them. Professor Schlichter had the most exacting signature of anyone I have ever seen. If I took in twenty checks, it was a two-hour ordeal, [Laughter] as he would sign these checks in an exacting way. You could have almost rubber-stamped every one on top of them. [Laughter] They were identical. Unbelievable! He would look at every item on the list and verify that all of the attachments and all of the supporting documentation tied in. As I say, it was only about twenty checks that I would bring up, and it was a two, two-and-a-half-hour ordeal every time. That was the extent of my getting to know the volunteers, until later on when I became an accountant and ultimately really as Controller. When I became Controller, I became much more accustomed to working with the volunteers. Then when I was promoted to the position of Assistant to the Treasurer, when Ray Sears was the Treasurer. I worked very closely with Ray Sears.

Aspray:

Fine man.

Bartlett:

I can never say enough about him. He helped shape my career. There was a time when I was thinking seriously of leaving the organization, and I did have an opportunity to go to another company. But Ray was always there, a steadying influence. He was just marvelous. He was a throwback to the kind of a person that I always knew in the old AIEE days.

Night School

Aspray:

Are there things we haven't talked about in the pre-merger era that come to mind to you that you'd like to mention? People or events or topics?

Bartlett:

I was so much thrown into daily work in those days, going to college nights for eight years and handling the accounting responsibilities. You put a great deal of pressure on yourself. You didn't have a lot of time for any outside activities. My wife would not get a television set in those years of college because she didn't want it to act as a distraction. She wanted me to study. Going to a vocational school and then to college was a traumatic experience. The college would not let me matriculate until after I maintained a straight A average for the first two years. So I was going to college un-matriculated, and I didn't know what was going to happen. I never had chemistry in high school, and I was required to take chemistry in college with all of those petroleum derivatives, etc. My wife and I would sit down weekends at the kitchen table, and she would drill me night after night in chemistry. I got an A in chemistry, which I felt she deserved more than I did. [Laughter] I think she could have gotten an A in that course. Really marvelous. She was so supportive.

Aspray:

I know you did not work with the organization during the war, but did you hear stories about how the war had affected the operations at AIEE?

Bartlett:

No.

AIEE/IRE Merger

Aspray:

Why don't we talk about the merger and all the problems that were encased in the differences between the organizations? Can you make the two organizations real for me, and the dimensions of the problem of bringing them together?

Bartlett:

Yes. The difficulty was that the two organizations communicated on the volunteer level, but never communicated on the staff level. There was jealousy, there was fear, there were power struggles on the staff level. You had two completely different methodologies of maintaining financial records, of maintaining membership records. The two organizations were just thrust together at almost a moment's notice without any real operational preparation. I don't want to in any way degrade anyone because these things can have an effect years from now. Some people were very, very dedicated to their particular society. They felt very strongly about their organization and wanted to do things a certain way. But by doing it that way and by not communicating, it created many difficulties — to say the least. When we brought the two membership rolls together, it was done in a way that there was no clear thought given to what this really means. We had about 15,000 to 20,000 individuals who were joint members, and it took us probably three to five years to out-sort those duplicate memberships. Because these members were getting two bills. What would happen is that the member would pay one, and their spouse would pay the other bill, and the member would have two different membership numbers. They didn't understand what was happening, and they didn't realize that they were only supposed to get one bill. There were errors that were made. The backlog of work was unbelievable. At the time of the merger, they moved the accounting department from the United Engineering Center to the Brokaw Mansion. IRE owned three buildings on Seventy-ninth Street, on the corner of Seventy-ninth Street and Fifth Avenue. Beautiful old French Renaissance buildings. We moved there. My office ended up to be what had been Clare Booth Luce's dressing-room. [Laughter] It was probably four times the size of my current office. It had an Italian marble fireplace in it. The safe that she kept her jewelry in became the petty cash safe. [Laughter] It had these French doors that opened up onto a veranda to overlook Central Park. If you can picture working in this kind of an environment, you know.... You'd take the bus or the subway and get off at Eighth Avenue early in the morning on purpose so you could walk across Central Park to come to work. It was an unbelievable feeling at that time. It was great except that once you were in the office, that feeling dissipated very quickly. [Laughter] There was not a great deal of camaraderie going on at that time.

But we struggled through it, and it turned out eventually that what happened is that one of the bookkeepers from the AIEE side and one of the girls of the cash department form the IRE side were married. That began the merger. [Laughter] It took us about two years to get to that level, and we felt finally the staff was beginning to come together at last. There were a lot of good people that unfortunately left. There was some hard feelings at the time, but we all came through it.

Aspray:

Were there still offices down on Thirty-ninth Street?

Bartlett:

No. We moved from Thirty-ninth Street to the new United Engineering Center in 1961. We sold the building on Thirty-ninth Street. For a while part of it became a garage, I understand, and may even be today. I don't know. The old United Engineering Center on Thirty-ninth Street had a connection to the Engineers' Club, which was on Fortieth Street. So that you could go from the United Engineering Center to stay — i.e. the engineers could — to stay at the Club. They had a terrific restaurant in there. They would have meetings and engineers could stay overnight. There was no air-conditioning in the club. A few times I had late meetings and I had to stay overnight, so I'd stay in the Club. You had these louvered doors almost like you were in India. And you had these big old fans going. When you closed and locked the door, it was a louvered door so that the air could pass through the room. That's how they would cool it. But the Engineers' Club eventually folded because they just couldn't maintain the level of services which other hotels could in the city.

Anyway, we moved into the New United Engineering Center in 1961. Two years later we merged, and then some of us went for a year to the Brokaw Mansion. We had the addressograph department there. They retained the IRE system, which was a combination of a Burroughs computer and the addressograph. The addressograph would send out all of the notices, but you needed the Burroughs system to do the financial record-keeping. It was not a good system. It gave us a lot of fits and troubles, and eventually was replaced with a GE 225 computer system. Then things began to evolve. We went from that to an IBM system. It took us several years and several difficult conversions. IRE had their print shop there and their membership department. In the No. 5 building, which I was in, the accounting department was located on the fourth and fifth floors. There were other offices on the third, second floors. The membership department and the addressograph were in the corner building, the No. 1 building. They had a boardroom there. Gorgeous. I guess it had been a formal dining-room of the Brokaw family. It had rosewood panels. All of the silverware was kept in drawers that would slide out from the wall. We sold the building. At the time, a group was trying to have the buildings declared as a historic landmark. When they sold the property, the builder came in on a Sunday afternoon and with a ball and knocked off the top of the buildings.

We got a heck of a write-up in the Sunday review of The New York Times as the "Rape of the Brokaw Mansion." I was very upset that this happened. They built the ugliest high-rise you could ever imagine in place of these gorgeous French Renaissance buildings. The building that I was in, which was No. 5, had a circular staircase that went up five stories. Hanging down through the center of this was a long chain, at the bottom was a chandelier, a light. All the time that I was there I kept eyeing that staircase and that bannister. I said, "I've got to try that." The day that we were leaving, I guess there were about 15 or 20 people that had stood down there, and I was going to come down the bannister. [Laughter] I came down the bannister. But after about the first floor, I felt like I was doing about 40 miles an hour; I thought I was going to kill myself because there was no way I could stop. I came off the bottom and ended up in a heap about 35 feet across the marble floor in the corner. Everybody was hysterically laughing at me. I must have been out of my mind to think that I could do anything like that, even to try it. It was a dumb, young thing to do.

Aspray:

Can you tell me about the experiences of some of the other staff members as the merger came about?

Bartlett:

Very similar to what I went through. A lot of frustrations. I was in a position at the time of having to almost separate myself from a lot of the detail work. It was my responsibility to bring together all of the financial records so that we could provide a financial statement to the Board, to let them know where we really were. Trying to delve into how the budgets were put together from the IRE and the AIEE and trying to bring all this together, trying to generate a new chart of accounts, so that I was a little bit removed from some of those daily in-fights that were going on. But I certainly was aware of them. I tried to smooth out things and tried to be as diplomatic as possible, to develop a team concept. And I kept saying — as management was saying — that, everybody was going to be taken care of.

Aspray:

What about in terms of the differences in the mission of the two organizations? How were they similar, and how were they dissimilar?

Bartlett:

Perhaps the biggest difference was the group structure that IRE had. The AIEE was structured towards geographical activities, to do things on a local level, at the section, and the region, and the branch activity. IRE, as I saw it, was designed to relate more on a technical level. You had all these technical societies, and you attempted to reach those people through publications. What eventually evolved was the Chapter program within the Sections, so that you could reach people on a technical level on a geographical basis. That was kind of an evolution that came out of the merger of having the Chapters. Even today, the Chapters do not work 100 percent effectively. It depends upon the local Section, how effective the Chapter is, how well it works within the Section's structure. To me, that is the right way of trying to reach an engineer technically — to do it on a local level.

Aspray:

Have there been any special interest technical groups within AIEE?

Bartlett:

There were some technical groups, but the only publications, were those three publications besides Electrical Engineering. There were some technical groups, but nothing at all like the formal structure that there was within the IRE.

Aspray:

I remember, I think correctly, that Ed Harder was telling me that he had the job of trying to merge the volunteer activities in relay issues, and that in AIEE it was an appointed group of representatives, whereas in IRE it was anyone who wanted to join. So you had two dissimilar kinds of organizations trying to merge.

Bartlett:

We were not aware of the kind of conflicts that the volunteers were running into. Apparently it was very similar to what we on the staff were experiencing: two different methodologies, trying to be brought together into a single effective organization. I guess they had their problems, too. Now I can look back and be sympathetic, but at the time we weren't. [Laughter]

Aspray:

How was top staff management chosen when these two were brought together? Did you see differences in mission and approach of people from the two organizations?

Bartlett:

How the selection process went through is difficult for me to say. I do know that as far as my position was concerned, they did get in touch with our auditors for their recommendation. They did have an outside organization come in and look at the staff and evaluate the staff and prepare a report. It was upon that report that I was promoted to the position that I had within the organization. So we felt that at least they were not doing it from a political point of view. They were trying to do it from a professional way in the business office. How they achieved merger within the editorial office, and how they did it within the technical activities, and the regional activities, I just don't know. I have no knowledge of that at all.

Aspray:

Did you see any difference in top-down management style? Or had the organization become so much larger at that time that the family notion of business had been lost a little bit?

Bartlett:

Yes. It had grown so that your immediate family became a smaller part of the total. How can I think of it? You've got lots of cousins, but you don't get intimately knowledgeable about what's happening in their lives. You stay with your brothers and sisters. That really what was happening, is that the departments were dispersed to different locations. The staff would get to know everybody. You'd say "hi" to each other and those kinds of things. But you didn't get tight with each other.

Move to Piscataway

Aspray:

Prior to the merger, how did the staff feel about moving from Thirty-ninth Street to the United Engineering Center?

Bartlett:

That was a good move. I think the staff didn't feel that they were being seriously displaced because it was still within Manhattan. There were some unsatisfactory comments. Particularly the women were concerned, because to have an office location that was between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, the shopping was just outstanding. You had Arnold Constable and all of the stores that were up and down Fifth Avenue there to do your shopping. In the U.N. area, there is zero shopping, and still today there is zero shopping. So they were unhappy with that. But at least they felt it was better than some of the other spoken-about moves. There was talk of moving to Pittsburgh. The Mellon Institute had proposed giving land to the United Engineering Center to move the entire operation to the Pittsburgh area. There was talk of Washington, D.C. So it was a lot better than what might have happened. Once they were within the building, they loved the building. They loved the new furniture; they loved the cleanness of the new building.

Aspray:

Was the work space better? Did it work out better?

Bartlett:

The work space was better, the lighting was much better. It was laid out in more professional, open areas. Instead of having lots of little cubbyholes, which is what we had at Thirty-ninth Street, you had a big open area. Then, of course, when we merged and moved up to Seventy-ninth Street, we were back into individual offices. It was very difficult to get things done there because you had to get down five floors and then walk through a tunnel to go to another building, to talk to somebody in another department. It was not good. So about a year later we moved back into the United Engineering Center. When the Center was originally completed, there were two floors left vacant on purpose for expansion. Well, we took those floors so that we were able to move everyone to one location. But even then, we were outgrowing it. So several years later we moved the administration and the business office to New Jersey. We initially rented some space. We were able to get the land that we're presently on here in Piscataway from AT&T. Ray Sears was very helpful in that. We bought the land from AT&T and the first building was put up.

That was a traumatic experience. Because then everyone was faced with the situation of you're either going to relocate or you're going to have a difficult commute. And so, unfortunately, we did lose quite a few with that initial move. But I would say that an even more difficult move was later on when we moved the rest of the operation here. We lost probably 70 percent of the staff when the rest of the office came out. Before we moved the accounting department and the computer center, the people were fully knowledgeable about what was going to happen, probably as much as two years in advance. So they began a trickle relocation by themselves. They began to buy homes and places in the New Jersey area and were commuting back to New York. Then when the move to New Jersey took place, they were already structured. We kept almost all of the accounting department. We didn't lose too many. We were fortunate. But it was a fight. I was opposed to the move, quite frankly. I didn't think it was good for the organization to again split itself into two locations. I thought that one location was more effective. I had seen what it was like when we had Seventy-ninth Street and Forty-second Street. It was difficult even then, at that close distance, to try to get things done effectively. And I felt here we're going to be forty miles away. How are we ever going to get anything done? Well, we've survived, grown....

Aspray:

Maybe this is a good place to stop for today.

Bartlett:

Okay.

Interview: Part Two

INTERVIEW: Thomas Bartlett INTERVIEWED BY: Loren Butler PLACE: IEEE Offices, Piscataway, New Jersey DATE: June 17, 1993

Accounting Department and Technology

Bartlett:

The Board or the General Manager, I'm really not sure, had an independent review by Price Waterhouse & Company to establish the recommended formal accounting department. At that time George Herman, who had been the business manager for the AIEE, was recommended to be the business and administration director for the IEEE. John Buckley, who had the similar role for the Institute of Radio Engineers, was appointed as his assistant. I was appointed as the accounting manager at that time, and both the accounting departments and cash-processing units all reported then directly to me. I, in turn, reported directly to George Herman.

After a number of years, a new responsibility came in the 1970's when Ray Sears, who had been the Treasurer at that time, asked that I be appointed as a special assistant to the Treasurer, and I would report directly to him. Most of my duties at the time had remained in New York, and the accounting department moved out to New Jersey. Earlier George Hermann had passed away rather suddenly, and Bill Keyes was selected to replace him. The offices moved to New Jersey, the accounting department, the computer operation, all moved to New Jersey at that time.

Butler:

From the time when you started to work as the accounting manager, could you talk a little bit about how the department was becoming automated, and what specifically your responsibilities were? What did you oversee?

Bartlett:

Initially, most of the financial record-keeping was on a manual basis. The general ledger was a manual general ledger. The accounts were in columnar forms. The individual financial support data such as cash-processing, disbursements, were all on manual ledgers. After they were entered that way, the totals would be manually transferred into the respective accounts. The books were probably 80 to 100 columns, each with subtotals. Everything was manual. The financial statements were drawn off manually. They'd be typed after they were done in pencil, so there was really no automation. One of the initial improvements was when the first ten-key adding machine came in. That really speeded up a lot of the process. The only thing that we had really automated up to that point in time was the ability of sending out the members' dues bills. That was on a combination computer and addressograph system. The posting to individual ledger cards was off the computer. We posted to the individual member's record for his dues, and the society affiliations came off the computer. But the generation of labels to send out the magazines to the individual was on the addressograph machine. And it was not until we brought in the IBM system that we began to really change the whole operation.

Butler:

And about when did that happen?

Bartlett:

Let's see.... About 1965, 1966.

Butler:

Was this something that most of the staff was excited about?

Bartlett:

This was a very exciting time? It was difficult for most of us; it was a learning process that we were all going through. But it was an exciting time. I think it's very similar to what's happening now with the whole major conversion that we're going through to the UNIX-type distributed network system. It's a very exciting time for the staff. Let me get back, though. The first thing that we automated, as I recall, was the accounts payable and then the cash receipts. Up to that point in time, as we would draw a check, it was a pegboard system. You would manually write the check, and simultaneously you would generate a ledger card and a journal all at the same time. The payroll was done exactly that way. We eventually transferred the payroll to an outside service bureau. The staff was getting larger at that time, and we found that it was better not to keep all that data within one or two individuals' hands, but rather to depend upon an outside service bureau for the generation of the payroll.

Butler:

And about how big was the staff at this point? We're talking about the mid-1960s, after the merger, and when things were really moving ahead as IEEE?

Bartlett:

I'm really guessing at this point in time, and I'd have to say probably about 150.

Butler:

That was the whole staff?

Bartlett:

Yes. And it was after the merger and after we settled down. It took about two or three years of settling down, eliminating duplicate positions. Some people retired, and some decided that they wanted to transfer locations. All of that took place over a period of about three years. About a year after the merger, the offices came back from Seventy-ninth Street. They sold the property at Seventy-ninth Street, and we were all located at the Forty-seventh Street address. And then shortly after that we located the accounting department and the computer operation into New Jersey on a temporary basis, until the building was constructed. Then we moved those departments into the new building. Membership also went over. Editorial stayed in New York. It was really the business office you might say that went to New Jersey. I would go to New Jersey really at that time only about one day a week because my responsibilities had been changed. I was then reporting independently to the Treasurer, so that he had a feeling that he had an independent audit function going on in the organization. That's really what my main responsibilities were.

When Bill Keyes left the organization, again there were some changes that took place. I was then brought back in and put in charge of the accounting, the computer operations, the order fulfillment, cash-processing, finance, the mail room, and warehousing. Four years ago, we created three associate general managers. One was responsible for business and finance; one was responsible for programs, and one was responsible for volunteer services. My initial responsibilities were really with the accounting and finance areas, and I had those functions reporting to me. It was only later on that I took on the additional responsibilities for the computer operation and other departments.

Butler:

So in a sense things were added to your responsibilities as new areas of activity opened up?

Bartlett:

Well, it was matter of as certain individuals left the staff they decided rather than to just replace those individuals, they continued to try to streamline the management style of the organization so as not to have too many individuals reporting to the general manager. And it was over a period of time, really, that those things took place. Throughout that entire period, though, there was rapid change of the technology. We were right in stride with what was happening in so many organizations. Computer operations changed several times. We upgraded several times. New systems were brought in. The whole reporting function, the entire record-keeping function was then totally on an automated basis. About the last thing that we automated were manual journal entries. Up until just very recently, journal entries were all still done on a manual basis, and then finally they were automated, and that's where we are now, where everything is on an automated basis.

Work Atmosphere in Mid-1960s

Butler:

Going back to that time in the mid-'sixties when the rapid changes started to occur, can you talk a little bit about what it was like to work here?

Bartlett:

The geographical separation between the accounting and the rest of the staff, I'd say, when we moved to New Jersey changed the ability that we had to interact as closely as we did with the rest of the staff. So in turn the business office almost became a separate company. We worked very closely and it was a very tight group of people. Some would party together. There was a certain group that would also try to do their social activities together outside the office. It worked very, very well. I'm trying to think of some specific references in the 'sixties. The hours were very long. A normal day would be eight a.m. to eight or nine o'clock at night, plus weekends. It was not unusual at all. Typical 70-, 75-hour weeks, you know. So the amount of socializing was nominal. [Chuckling] They did, after a while, try to get together, and they would at least have the annual picnic, they would have softball games and things like that. As more and more departments began to move to New Jersey with the additions to the building there, we began to get back into the type of a situation where it was like one big organization again. But the New York operation was still separate.

Butler:

Within the group of people you worked with over the period of the 1960s, was there a great deal of staff turnover?

Bartlett:

No, no. Not really. There was some turnover, but a lot of the key people had been with me a long time. Ed Rosenberg has been with me over 25 years, Mike Sosa 35 years. Mike also started out in the mail room and grew from there. Mike is in charge of investments and has an outstanding reputation with what he has done in the investment field. In fact, he taps out in probably the top 1 percent of the nation in investment of fixed instruments, which is kind of amazing. It really is.

Butler:

Certainly.

Bartlett:

The investment community continues to be completely nonplussed by his performance year after year. Ed Rosenberg is probably one of the hardest-working individuals that I've ever had the pleasure of working with — and is now the Controller of IEEE. His typical week, still today, is 70, 75 hours. And he has a number of long service people with him. Again, there has been some turnover, but there's been a lot of internal growth. Historically, that has always been the theme within the IEEE: the ability of individuals to move and prosper and grow in the organization. Typical case in point was Ed Rosenberg's previous secretary, Peg Pascale. She is now the supervisor of the accounts payable department. She moved into accounts payable, grew up with the system, and now is in charge of it. She has learned the new system, and is functioning in an outstanding manner. There is so much of that, so many departments have the same experience. John Powers has been very adamant that whenever there is an opportunity for an opening, first we go internally to try to give an opportunity to someone. Even if it's transferring from one department to another, the opportunity first is presented in-house, and we ask, does the individual have the skills necessary to do the job? And if the individual wants it, that individual is then given that opportunity. So it's great.

Butler:

Is this something that general managers from earlier times also encouraged?

Bartlett:

Not as much as John has. John has made it a policy. For others, it was a situation of allowing it to take place. But with John you don't fill a job from the outside. You first find someone — if there is someone internally — to fill that position. Then only after you are unsuccessful for several weeks — do we look outside. It's really a planned arrangement.

Butler:

Okay.

Bartlett:

Back in the 'sixties, I was really much closer related with Bill Keyes, when Bill was the chief financial officer on staff, and I reported to him as the accounting manager. But that was up until about 1970. And around that time, I was reporting directly to Ray Sears.

Butler:

Is the Treasurer a volunteer?

Bartlett:

The Treasurer's a volunteer, yes.

Relationship between Staff and Volunteers

Butler:

In general, did you find it to be difficult to work part of the time reporting to people on the staff and part of the time to volunteers?

Bartlett:

Yes. I felt very much the way an auditor feels. And it was difficult. I had to be certain that I would keep the openness amongst the staff and myself. I had a reporting responsibility, but it was never to be like "you're ratting on people." What you were really trying to do was to educate the Treasurer because the Treasurer comes into a situation that is not his regular nine-to-five job. He has a responsibility of reporting to the Board. If things were going wrong, and he wasn't aware of it, then he was the one who would be embarrassed before the Board. That you did not want to let happen. There are always situations in any organization where there are mistakes and errors, and there is a tendency to try to cover them up, hoping that in time they will go away. I had the responsibility to make sure that the Treasurer was aware of these situations and whether or not I felt that those situations were serious enough that action had to be taken somewhere in the organization. Or whether it was just a temporary problem, that would get itself resolved, and then I would advise him how they were approaching it. He made the decision whether or not to advise the Board.

Butler:

When was this particular relationship established between the staff and the volunteers?

Bartlett:

That was really with Ray Sears. When Ray became the Treasurer, he felt it important to have a person reporting directly to him, and I was selected to be that individual. I was able to keep a good rapport with the staff. At the same time I had had a long experience and knowledge of the entire accounting function, so it was relatively easy for me to dig into these matters and see where there were items that needed to be addressed. Then I would work out with Bill Keyes how those situations were going to be resolved. Bill and I had a good relationship and we were able to keep it that way. It continued until Bill left the staff. He went with a for-profit organization, a steel company, as I recall. He wanted to get back into the for-profit world. A lot of people don't like the not-for-profit world. It's a completely different type of function. When Bill left I was assigned almost all the responsibilities that Bill had in the past.

Growth of IEEE

Butler:

During this period IEEE membership was growing very fast. How did that affect your responsibilities?

Bartlett:

The numbers didn't really affect my responsibilities. You wrote a little bit bigger numbers on your financial reports, [Laughter] which was kind of nice. The number of members did not affect my areas of responsibility at all, other than the fact that you were processing more payments. We had automated at the time, so a lot of the work fell into the computer operations. It was no longer manual — thank God! We were constantly studying and evaluating new methods and ideas, to try to maintain a prompt response to the members' needs. That was really very critical to us. You still had the problem that the examination of records took time. It was really only now with the new system that we will have a much faster response time in accessing a member's record, finding out what the problems are, and being able to handle telephone calls. The concept of being able to handle telephone inquiries and give an immediate answer was totally impossible on the old systems. And as a result there was a great deal of letter writing. That's what we're trying to avoid now with the new system, where we can immediately respond to a telephone call and tell the member what the problem is with the record, and what his status is on the record. That's important.

Butler:

As IEEE was growing and diversifying, and new technical societies were forming and so forth, did that create new accounting issues as well?

Bartlett:

Oh, it did create additional difficulties of trying to keep all the volunteers happy. That's probably the biggest problem. With each new group of volunteers, they have new ideas, new methodologies, that they would like to impose upon you. Yet we still had the responsibility of trying to put together a consolidated financial statement so that at the end of the year we could report on a consolidated basis — as we have to. But the individual societies each had their own methodology for what they wanted to see. For us, at that time, to create individual financial statements that were different from each other was just totally impossible. Now with the new system, we will have that capability. We can rearrange accounts into whatever systematic method that the individual society would like to see, and then pull them all back together again and still put out a consolidated report. That's something that we could not do before. The amount of detail that we can provide to a society is much greater today than ever before.

Turnover of Volunteers

Butler:

Starting in the early 'seventies when you began to have direct contact with the Treasurer, was there a lot of turnover among particular volunteers you worked with in contrast with the continuity of the staff?

Bartlett:

Yes. We saw a turnover on the Board of close to 50 percent every year. To have the Treasurer for more than two years was a rarity. We had Ray Sears for three years. Now we will have Treasurer, Ted Hissey, for three years also. A number of treasurers have served for only one year. Occasionally you'll get a Treasurer who has absolutely no financial knowledge at all. That's always a difficult experience. It's a very rewarding one, in a sense. You take a lot of pride in — I can't say in shaping — but in helping a Treasurer to fulfill his responsibilities. You see how a Treasurer starts out his role with the Board, and you watch him over a period of three to four meetings, and he becomes skilled, he becomes knowledgeable, he becomes much more sure of himself. And it's interesting. There has to be a very, very close relationship between the Treasurer and the financial individual, whoever that person is. That has to be tight. Telephone calls almost daily. A lot of meetings.

Butler:

Did you attend the Board meetings?

Bartlett:

I always attended all Board meetings, Executive Committee meetings, finance meetings, budget meetings, and Investment Committee meetings. I would be on the road quite a lot.

Growth and Change

Butler:

How about the other members of the staff? Were you the only one who had to travel?

Bartlett:

Except for the corporate office, I would be the only one who did all the traveling. We were always trying to minimize the costs. On occasion I would have Ed Rosenberg — especially much more recently — attend a Board meeting because I thought it was good for him to get the experience and exposure. But when you go to a Board meeting, it was more than just a meeting. It was a Board week. You had the U.S. Activities Board meeting and their financial people; you would sit in on the Educational Activities, the Regional Activities, the Technical Activities, the Executive Committee, and the Board. There were many meetings going on simultaneously, and you were running back and forth between two rooms trying to handle all the different problems and questions that would come up. So you got a lot of exposure and a lot of knowledge. You had to know what was happening. You had to do a lot of reading of the minutes that would come out of meetings. Because if you were to attend, let's say, a Technical Activities Board meeting, maybe you were only there for an hour and a half, maybe two hours, and yet the whole meeting would be going on for seven or eight hours, so you'd miss a lot of things, and you'd have to rely upon following the action items of the minutes that come out from the meeting. TAB has grown tremendously. Now there are probably five major subcommittees of the Technical Activities Board and different individuals will now attend each of those meetings. Some have to do with the periodicals, some have to do with the publishing, some have to do with finance. And there's all different meetings in addition of the administration and the Technical Activities Board itself. So we're growing; there's no two ways about it. We're getting much more complex.

Butler:

Do you see this growth as having been sort of constant over time? Or did things really take off at one point?

Bartlett:

Seems to be step functions. A particular activity will be relatively steady, and then an individual will come in who might be the vice president. He will move that area up in a definite step function of change.

Butler:

Could you give an example of such a change?

Bartlett:

When Troy Nagle was vice president of Technical Activities, there were major changes. The whole Technical Activities Board was completely reorganized, and many, many different committees were established, trying to improve the flow of the information to the different societies. With the growth of societies, you have the tendency of a breakdown in communications in different areas. What he was trying to do was eliminate that breakdown in communication, and to speed up the flow-through of information. So instead of having one or two committees, you might have jumped to seven or eight committees. RAB is trying to emulate that. They are also creating a number of individual committees now. Whereas before almost everything was handled by a Regional Activities Board, now they are being broken down into many different committees. They had smaller committee structures before, but they didn't have the authority that the individual committees have now.

US Activities Board

Butler:

Do you remember any dramatic points of change in the earlier periods, in the 'sixties or 'seventies?

Bartlett:

USAB certainly was a significant change, when the U.S. Activities Board was created. It stared out with a modest investment of about $120,000 to try to establish U.S. Activities activity. It's grown now to be a major part of the IEEE.

Butler:

And where did the impetus for establishing the USAB come from? Do you remember?

Bartlett:

A former president also.

Butler:

So one of the former volunteer presidents came to the IEEE Board and said, "Could we have..."?

Bartlett: