Hedy Lamarr: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== '''Hedy Lamarr'''<br> | == '''Hedy Lamarr'''<br> == | ||

Born: November 9, 1913 | Born: November 9, 1913 | ||

Revision as of 20:10, 6 October 2009

Hedy Lamarr

Born: November 9, 1913

Died: January 19, 2000

Hedy Lamarr, famous as a Hollywood film star in the 1930s, was not only one of the most acclaimed actors of her time but also the co-inventor of an important communications technology. She was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in Vienna, Austria, in 1913. As a teen, she took an interest in acting and attended a famous acting school in Berlin, landing a role in the film Ecstasy, a project that became controversial because of the nudity it contained-- the film featured perhaps the first nude scene in cinematic history. She was eventually hired by the American studio MGM and began making films in Hollywood. Lamarr had a long acting career, starring in several successful films, including the popular Samson and Delilah. Louis D. Mayer of MGM called her “the most beautiful girl in the world.”

Lamarr's first husband (of six), Fritz Mandl, was a munitions manufacturer in Berlin, and in the 1930s he became interested in control systems for aircraft. Mandl and Lamarr attended hundreds of dinners and meetings with arms developers, builders, and buyers until the marriage broke up in 1937. That year, Lamarr, an anti-Nazi of Jewish descent, escaped to London.

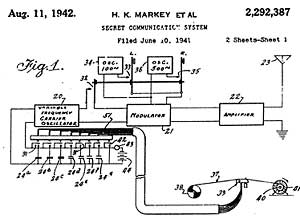

Clearly Lamarr learned something from the numerous meetings she attended with her former husband. She introduced the concept of "frequency hopping" as a strategy to combat Adolf Hitler's war machine. She met her collaborator, an avant-garde musician named George Antheil, at a 1940 party where Lamarr proposed the idea of "frequency hopping" during discussion of radio remote control of torpedoes. The pair applied for a patent on a device that would reduce the danger of detection or jamming for radio-controlled torpedoes. Although the idea of radio control for torpedoes was not new, the concept of "frequency hopping" was. Broadcasting over a seemingly random series of radio frequencies, switching from frequency to frequency at split-second intervals, prevented radio signals from being jammed. The receiver would be synchronized to the transmitter to allow the two to jump frequencies together. If both the sender and the receiver were hopping in sync, the message would transmit clearly. Anyone trying to eavesdrop would hear only random noise, similar to a radio dial being spun. Lamarr developed the idea of radio control; Antheil's contribution was to suggest the device by which synchronization could be achieved. After consultation with a California Institute of Technology Professor, Lamarr and Antheil obtained their patent on a "Secret Communication System" on August 11, 1942.

Lamarr and Antheil sent their ideas to the National Inventors Council, a body that searched for inventions that could be used in the war, but the Council did not seem interested. By 1957 the concept was taken up by engineers at the Sylvania Electronic Systems Corporation. In 1962, three years after the patent expired, the pair's idea was used in military communication systems installed on U.S. ships sent to blockade Cuba. Subsequent patents in frequency changing have referred to the Lamarr-Antheil patent as the basis of the field, and the concept lies behind the principal anti-jamming devices used today, for example, in the U.S. government's Milstar defense communications satellite system. Frequency hopping, in greatly modified form, is used to send secure wireless transmissions in many different communications systems.

By the late 1940s, Lamarr’s film career was in decline, but she made television appearances on programs such as The Bob Hope Show in the 1960s. Neither Lamarr nor Antheil ever received royalty payments for the commercialization of their patent. Their invention, moreover, was only formally acknowledged by the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) in March 1997. Antheil had died in 1959. Lamarr's son, Anthony Loder, received the EFF award on behalf of his mother, then an 83-year-old Florida retiree.

Further Reading

Spread Spectrum: Hedy Lamarr and the Mobile Phone.

Rob Walters. Booksurge Publishing, 2006.