First-Hand:Adventures at Wartime Los Alamos: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

'''Contributors:''' Lawrence Johnston, IEEE Life Fellow. Submitted on his behalf by the IEEE History Center Staff. | '''Contributors:''' Lawrence Johnston, IEEE Life Fellow. Submitted on his behalf by the IEEE History Center Staff. | ||

This article will discuss three major topics. First about how we experienced life in wartime Los Alamos. Second, the work we did on the Fat Man Implosion type of bomb, and third, the three wartime bomb events: the Trinity Test of the Fat Man bomb, and the job that took us to the Tinian Pacific base, and the delivery missions of the bombs to Japan - Hiroshima and Nagasaki. | This article will discuss three major topics. First about how we experienced life in wartime Los Alamos. Second, the work we did on the Fat Man Implosion type of bomb, and third, the three wartime bomb events: the Trinity Test of the Fat Man bomb, and the job that took us to the Tinian Pacific base, and the delivery missions of the bombs to Japan-- Hiroshima and Nagasaki. | ||

== Life at Wartime Los Alamos == | == Life at Wartime Los Alamos == | ||

| Line 239: | Line 239: | ||

This time Kistiakowsky was convinced, and soon South Mesa was buzzing with testing and manufacturing of Exploding Bridgewire Detonators. Indian women were brought in from nearby pueblos to do the assembling and loading, and SED soldiers were in charge. Those women got real good at soldering the bridgewires on the entrance plugs and loading the explosives. The “solder” we used was Wood’s metal, melting at 70 degrees C. This was to avoid overheating the wires in the plastic plug, especially since we found that the detonator worked best if the bridge wire was laid flat against the end of the plug. Wood’s metal: 50%Bi, 25%Pb, 12.5%Sn, 12.5% Cd. Probably by weight. Soon all the Implosion tests on the Hill were using our exploding bridgewire detonators. It is interesting that when the time came in 1944 to patent the EBW detonator, Alvarez said that the patent should be in my name only, since I had done all the work. He could have taken the view that I was only the technician who carried out his ideas. Patent 3,040,660 was granted in 1962. (SED "Special Engineering Detachment" soldiers were young men who had been drafted into the army, who had special skills, such as electronics or chemistry. Los Alamos requested their services. These soldiers seemed happy to be doing things at Los Alamos, rather than fighting on foreign soil.) | This time Kistiakowsky was convinced, and soon South Mesa was buzzing with testing and manufacturing of Exploding Bridgewire Detonators. Indian women were brought in from nearby pueblos to do the assembling and loading, and SED soldiers were in charge. Those women got real good at soldering the bridgewires on the entrance plugs and loading the explosives. The “solder” we used was Wood’s metal, melting at 70 degrees C. This was to avoid overheating the wires in the plastic plug, especially since we found that the detonator worked best if the bridge wire was laid flat against the end of the plug. Wood’s metal: 50%Bi, 25%Pb, 12.5%Sn, 12.5% Cd. Probably by weight. Soon all the Implosion tests on the Hill were using our exploding bridgewire detonators. It is interesting that when the time came in 1944 to patent the EBW detonator, Alvarez said that the patent should be in my name only, since I had done all the work. He could have taken the view that I was only the technician who carried out his ideas. Patent 3,040,660 was granted in 1962. (SED "Special Engineering Detachment" soldiers were young men who had been drafted into the army, who had special skills, such as electronics or chemistry. Los Alamos requested their services. These soldiers seemed happy to be doing things at Los Alamos, rather than fighting on foreign soil.) | ||

By that time the engineers were designing the configuration of the final military weapon, the bomb that could be loaded into an airplane and dropped, and they adapted our detonators to that design. We were now merely consultants. So I felt free to join Alvarez in a new venture he had taken on. | By that time the engineers were designing the configuration of the final military weapon, the bomb that could be loaded into an airplane and dropped, and they adapted our detonators to that design. We were now merely consultants. So I felt free to join Alvarez in a new venture he had taken on. | ||

== Three Wartime Bomb Events == | |||

Revision as of 16:33, 17 September 2008

Adventures at Wartime Los Alamos

Contributors: Lawrence Johnston, IEEE Life Fellow. Submitted on his behalf by the IEEE History Center Staff.

This article will discuss three major topics. First about how we experienced life in wartime Los Alamos. Second, the work we did on the Fat Man Implosion type of bomb, and third, the three wartime bomb events: the Trinity Test of the Fat Man bomb, and the job that took us to the Tinian Pacific base, and the delivery missions of the bombs to Japan-- Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Life at Wartime Los Alamos

When I say "we" I mean Luis Alvarez and me. Of course there were others involved. I was just out of Berkeley as a physics major when the War in Europe started (I was born in 1918), and I hitched the start of my career to this fascinating man, Alvarez.

It is interesting that Alvarez in turn considered himself to be a disciple of Ernest Lawrence, now regarded as the founder of the "Big Science" trend during and after the War. Lawrence had a big hand in establishing and staffing the MIT radar lab, the Metalurgical Lab in Chicago, and Los Alamos.

As the war and technology went forward, Lawrence followed the progress of each Lab, and which lab most critically needed the help of particular scientists. Thus in early 1944 Lawrence decided that the now critical work at Los Alamos on the Fat man bomb needed the insights and ideas of Luis Alvarez; and Alvarez brought me.

Now about wartime Los Alamos living: Was it burdensome living in such an isolated environment? It may have been for some people with a liking for urban civilization, but for us, a young couple with a one-year old, it was an adventure. To us, it was more like living in a wilderness resort. On a weekend, you could take scenic hikes where the beauty started right at your back door. And we could see the pine forest starting right outside our kitchen window. Here is the kind of 4-plex apartment building we lived in (below).

Here are a few of my outstanding memories:

▪ Steak night each week, at the cafeteria. A great chef. Meat was under wartime rationing, but no ration coupons were needed at the cafeteria.

▪ On a hike, seeing a tree blown to kindling wood by lightning. Lightning at Los Alamos? Tell me about it! This was poignant, because just the day before the talk we experienced the fiercest lightning storm any of us had ever seen. Drenching rain and frequent lightning and hail. They said later there was 1.9 inches of rain, in less than an hour.

▪ The Easter 1945 sunrise service outdoors. Jim Roberts, a Physics professor from Northwestern University brought the inspiring message of Jesus' resurrection.

Here is an interesting anecdote. When you were expecting a new member of the family, you went to the housing office and put up a card on the bulletin board. Accordingly when Geraldine Alvarez was expecting, they placed a card on the board applying for a larger apartment for the Alvarez family. At the next meeting of the town council, the wife of a well-known Austrian physicist came and complained that they were allowing those Spanish American workers named "Alvarez" to live in the prime housing of the site. Alvarez was a very good friend of this woman's husband, and they both got a big kick out of the incident. However, a subsequent conversation with Geraldine Alvarez herself in September 2006 indicates this story is not true. But she says there were complaints from the other occupants of the apartment building. Since we lived in the apartment just below the Alvarez’s, that leaves two families that may have complained.

Another incident-- I got a speeding ticket from one of the military police, and appeared before a court of 3 townspeople. I was fined $5 by the presiding judge, a very likeable Victor Weisskopf. He was one of the prime theorists there. More on that occasion.

Going back to my arrival at Los Alamos, I got off the train at Lamy, May 8, 1944. My wife and baby would arrive 2 weeks later. I was met by Alvarez and Kistiakowsky. We drove to The Hill in an army sedan, chaufeured by an army woman, a WAC. On the way they briefed me on the situation they faced. The Implosion bomb, the "Fat Man" had recently been given very high priority at the Lab, and Kistiakowsky had been brought in to head up a new Explosives Division. Alvarez had been there a few weeks, as his chief troubleshooter.

We stopped at the Santa Fe office to get me properly registered. Dorothy McKibbin gave me a white numbered badge to wear, and a pass card which indicated that I had a Q clearance, which meant I could be told anything in the Manhattan Project. It occurs to me that one reason for having both Alvarez and Kistiakowsky with me was to certify my identity with Dorothy, before she gave me the credentials for Los Alamos.

I found Kistiakowsky's office and he and Alvarez were soon telling me about the status of the Fat Man implosion bomb, and their problems with it.

Work on the Fatman Implosion Type Bomb

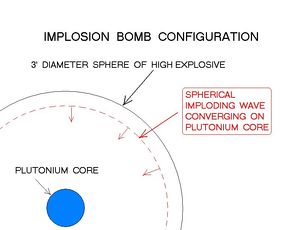

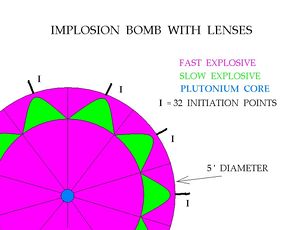

The idea of the Implosion bomb is to have an almost critical plutonium sphere and make it go supercritical by compressing the metal so all the Pu atoms get closer together. The compression is done by surrounding the metal with a large sphere of high explosive. To uniformly compress the metal, the explosive sphere is imploded, that is, a spherical wave of detonation starts at the outside of the sphere, and converges inward to compress the central plutonium ball.

This imploding wave is a very unnatural thing to accomplish, since most wavefronts go outward from the starting point, like the ripples when you throw a pebble in a pond. It takes a special optical system to make a converging wave out of a diverging one. A great deal of Los Alamos talent went into solving this problem.

The theoreticians and explosives people decided they would need to produce the converging wave in a piecemeal fashion, and then join up the partial waves further in to make a complete converging spherical wave. A very ambitious undertaking.

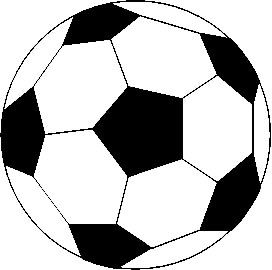

So they conceived of the surface of the explosive sphere as divided up into 32 areas, like the patches on a soccer ball, and they would make 32 separate optical systems to feed a converging explosive wavelet into each such area.

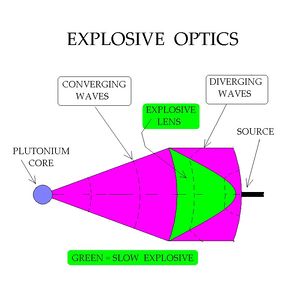

The usual way to do this with an ordinary light optical system would be to use a glass lens (right).

Light travels more slowly in glass than in air, so the central parts of the wavefront get delayed more than the edges. This transforms an outward-going diverging wave into a converging one.

So the explosives experts invented an explosive lens that would perform the same job, assuming that explosive waves obeyed the same optical laws of propagation. They made their explosive lenses out of a slow-propagating explosive.

Here is the same optical system, in the explosives regime (below).

So when 32 of these explosive lens sectors were assembled around the inner sphere, they could produce wavelets that would join up to make the required large converging wave.

Parenthetically, I would like to pay tribute to the skill and courage of those men who made those lenses and other explosive components of the bomb, out at S site. They first poured molton explosives into roughly shaped molds, and then machined the molded blocks into the precise shapes needed to fit together in the bomb assembly. I picture all this casting and machining to be precarious work, on explosive blocks of 50 to 100 pounds. Any slipup could have been lethal. I have not heard of any such accidents in the explosives fabrication program. You always wondered when you heard a big boom coming from several miles South of town.

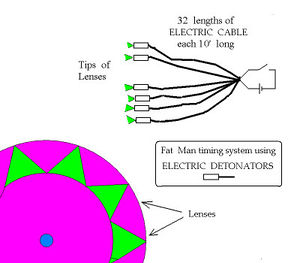

All that is then needed is a way of starting the tips of all those 32 lenses at exactly the same time, so each lens system contributes its timely matching sector of the spherical imploding wave. When I arrived on the scene, the way of doing this was the way an explosives man would think of: Do it with explosives. They would use a harness of 32 10' long pieces of Primacord, a kind of explosive cord that is filled with a very fast high explosive. You could simply transfer an explosion from here to there, by joining the two places with a length of primacord.

This system of timing the lenses resulted in a scatter of lens timing events in the tens of microseconds, which was not nearly good enough for the requirement, that all the lenses should initiate within a tenth of a microsecond. This scatter was due to slight variations in the propagation speed of the wave in the primacord, and perhaps even the bending pattern of each cord. What was their solution? To try to get DuPont to make better primacord!

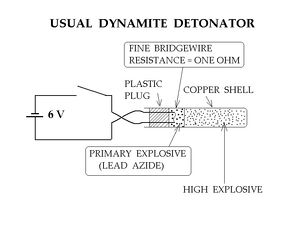

When Alvarez heard of this problem with the primacord timing, he suggested to Kistiakowsky that instead of 32 lengths of primacord, they should use 32 lengths of electric cable, each ending in an electric detonator. The speed of electric signals is 30,000 times faster than the speed in primacord. (There's a 6-volt battery to set them all off) But Kistiakowsky smiled and told him that the problem is that electric detonators have a long time delay of milliseconds before the full explosion starts.

Here's a usual dynamite blasting detonator, about a quarter inch in diameter (right). A 6-volt signal makes a tiny bridge wire glow red hot, and that starts a primary explosive burning, and that burning rapidly accelerates into a detonation, which starts the high explosive at the end.

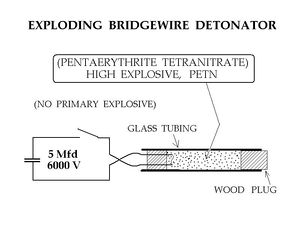

Alvarez then came up with his celebrated idea that instead of burning that bridgewire with 6 volts, the wire could be made to explode by applying a much higher voltage - maybe 6000 volts. This small explosion might be able to start a high explosive directly, with no primary explosive and very little time delay.

So soon after I appeared in Kistiakowsky's office that first morning, they asked me to try out this idea for an ultra-fast electric detonator. It didn't take long to get something started, in those days, with all the services and supply storerooms available on the Hill, and the lack of red tape. I assumed that there was now plenty of red tape at Los Alamos, but nobody clapped. My conjecture was amply fulfilled when I later went thru the process of collecting my travel expenses. Within two days I was the sole proprietor of South Mesa, which was then a sagebrush covered few acres of territory. South Mesa is now densely built up. Most of the Tech area is now on South Mesa.

I had a government automobile, a 15x15 foot hutment delivered and erected, an electric generator, a work bench, a set of hand tools, a surplus high voltage power supply, an assortment of high-voltage capacitors, a box of 25 Dupont electric blasting caps, some lengths of glass tubing from the Chemistry Storeroom, and a 100' roll of primacord. If only I had thought to get some ear plugs, to protect my ears! But we were in a hurry.

My first experiment out on South Mesa violated most of the safety rules in the book. I did not have any such book, and I probably wouldn't have stopped to read it anyway. But I imagine one rule would have said "Never play with blasting caps, and never, never try to take them apart to see what's inside." As an aside, one of our young daughter's favorite toys was a box of those discarded yellow cardboard tubes in which the detonators came.

I took one of those blasting caps out of the box, pulled it out of its yellow cardboard tube, and straightened out the folded-up wires. I examined the copper shell critically, and noticed that where the wires went into the shell, some of the thin copper shell projected. It couldn't hurt to work on that, could it? So I used a pair of long-nosed pliers to grab that thin shell, and gently twisted it. The shell split open a bit, and when I twisted some more I noticed that the plug with the wires was loosening. It couldn't hurt to wiggle the plug out of the shell, could it?

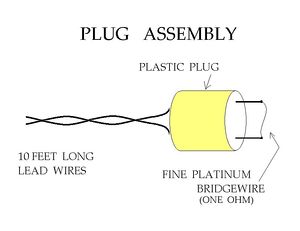

So soon I was holding the wires, with a free plug on the end of them, and I saw that there was a fine bridgewire soldered to the stubby wires projecting through the plug. And I still had all my fingers, and both eyes. (I could easily have been wearing safety glasses!)

To construct the new detonator, I cut off a 2" length of glass tubing, and inserted the plug with bridgewire into one end. It fit nicely, so I glued it in place with DeKhotinsky cement. Now I was ready to add the high explosive, so I cut off a hunk of that primacord, and slit it open to get some PETN, that sensitive high explosive white powder I was told about; I poured it into the open end of the glass tube. I closed the system by pushing a wooden plug into the open end, and the new detonator was ready to try.

I poked it outside the door of the hutment, with the long wires inside. I started up the generator and charged up the capacitor to 6000 volts, and using an insulated screwdriver as a switch, touched the second wire of the new detonator to its terminal. Blam! It must have worked, and with no primary explosives to slow it down! There were glass fragments stuck in the outside of the door . Wow!

I jumped in the car and drove to Kistiakowsky's office, and yelled "It worked"! Kistiakowsky looked up and said what worked? When I told them what I had done, Alvarez was an instant believer, but Kistiakowsky said it might have been a low-order explosion. How long did it take for the explosion to get going? Parenthetically, this occasion is probably when I got the speeding ticket.

So to answer that question, I spent several days setting up an oscilloscope with a polaroid camera in a way to show the time delay, as an electronics person would do it - - the delay between the firing voltage spike and the arrival of the explosion along a short piece of primacord. When I got things working, I had a polaroid picture showing there was less than 2 microseconds delay. Again I jumped in the car and to Kistiakowsky's office. I put the picture on his desk, but he scarcely looked at it. He said This picture convinces you and Alvarez, and maybe it does me, but my explosives experts will only believe in results using purely explosives methods.

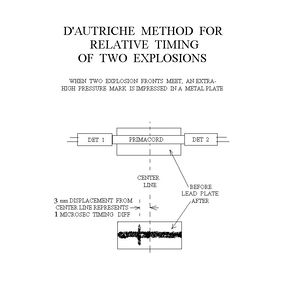

So he told us of a simple experiment we could do, which would show how closely the timing of two detonators compared, and that, after all, was what was needed for the bomb.

The two detonators to be timed are connected to opposite ends of a short piece of primacord. A lead plate is taped to the primacord, and a line is inscribed halfway between the two detonators. If the two detonate at exactly the same time, the two explosive waves in the primacord will meet in the middle, and produce an extra-high pressure mark in the plate. If one of the detonators is a little late, the waves will meet closer to that detonator, and the mark will indicate the relative timing. I made the assembly and ran the wires into the hutment, where the power supply was. Further reflection reminds me that this was assembled on a wooden 2x4, and that the wood was shattered in the explosion. I fired it, and then went outside and found the lead plate, about ten feet away from ground zero, under a bush. the mark was plain to see, indicating that the difference was about one microsecond, not bad for the first try. I grabbed the plate and drove in to show it to Kistiakowsky and Alvarez.

This time Kistiakowsky was convinced, and soon South Mesa was buzzing with testing and manufacturing of Exploding Bridgewire Detonators. Indian women were brought in from nearby pueblos to do the assembling and loading, and SED soldiers were in charge. Those women got real good at soldering the bridgewires on the entrance plugs and loading the explosives. The “solder” we used was Wood’s metal, melting at 70 degrees C. This was to avoid overheating the wires in the plastic plug, especially since we found that the detonator worked best if the bridge wire was laid flat against the end of the plug. Wood’s metal: 50%Bi, 25%Pb, 12.5%Sn, 12.5% Cd. Probably by weight. Soon all the Implosion tests on the Hill were using our exploding bridgewire detonators. It is interesting that when the time came in 1944 to patent the EBW detonator, Alvarez said that the patent should be in my name only, since I had done all the work. He could have taken the view that I was only the technician who carried out his ideas. Patent 3,040,660 was granted in 1962. (SED "Special Engineering Detachment" soldiers were young men who had been drafted into the army, who had special skills, such as electronics or chemistry. Los Alamos requested their services. These soldiers seemed happy to be doing things at Los Alamos, rather than fighting on foreign soil.)

By that time the engineers were designing the configuration of the final military weapon, the bomb that could be loaded into an airplane and dropped, and they adapted our detonators to that design. We were now merely consultants. So I felt free to join Alvarez in a new venture he had taken on.