Archives:Transformers at Pittsfield, part 1: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 204: | Line 204: | ||

[[Image:Blalock - page 13 (top).jpg|thumb|center|Early Power House Interior: Hall of Electrical History]] | [[Image:Blalock - page 13 (top).jpg|thumb|center|Early Power House Interior: Hall of Electrical History]] | ||

[[Image:Blalock - page 13 (bot).jpg|thumb|center|View west from railroad bridge in 1922 (Building 31 on left): G.E. Current News, April, 1922]] | [[Image:Blalock - page 13 (bot).jpg|thumb|center|View west from railroad bridge in 1922 (Building 31 on left): G.E. Current News, April, 1922]] | ||

<u> Synopsis of Power House History </u> | <u>Synopsis of Power House History </u> | ||

By 1915, major substations in the plant were located in, or near, Buildings 4, 12, 15, 41, 42, and 43 on the North Side, and Buildings 26, 32, and 33 on the South Side. In addition, there was a separate set of feeders from the Power House to the main transformer testing facility in Building 12 (because of the large amount of power required by that operation). | *1900 - original power house constructed | ||

As a matter of interest, all of the steel buildings in the plant were connected electrically by means of a large diameter copper cable; this, in turn, connected to a grounding plate at the bottom of nearby Silver Lake! | *1907, 08 - two 500-kw, two-phase vertical turbines installed | ||

The substations served to step down the voltage from the Power House to: | *1910, 11 - two 1500-kw, two-phase four-stage turbines installed | ||

110/220 volts single-phase | *1915 - 2500-kw, two-phase horizontal turbine installed | ||

440 volts three-phase | *1930's - experimental mercury turbine installed | ||

550 volts two-phase | *1941 - 3000-kw, two-phase horizontal turbine installed | ||

The three-phase system, as it evolved in the plant, operated at 13,800 volts (13.8-kv). In 1936, switch-gear was installed in the Power House in anticipation of an interconnection between the plant and the lines of "The New England and Turner's Falls Power Company". These were 115-kv lines which terminated at the Silver Lake Station of the Pittsfield Electric Company. | *1946 - two 7500-kw, three-phase horizontal turbines installed | ||

Two Pittsfield-built transformers were installed near Silver Lake. These had dual secondary windings. One winding connected with the 13.8-kv three-phase plant power system, while the other winding connected: with the 2300-volt two-phase plant power system (via a phase-changing winding connection). | *1950 - 7500-kw, three-phase mercury turbine installed | ||

The mercury turbine installation referred to above was the result of development work in the use of mercury vapor as a more efficient alternative to high pressure steam for driving turbines. Complications in the | *1960 - mercury turbine removed | ||

the usage of vast amounts of toxic mercury!). | *1970 - power house ceases generation; provides steam only | ||

For some time prior to 1970, General Electric had a cogeneration agreement with the Western Massachusetts Electric Company whereby they purchased any excess power available from the Power House. | |||

During the 1980's, it was determined that the Power House could not be brought up to existing pollution standards. Accordingly, G.E. instigated the construction of a new cogeneration plant on property which they owned to the east of the main plant. The plant Power House was then completely shut down. Today, the new plant sells electric power to Northeast Utilities, and sells steam for heating purposes to General Electric. | |||

When in full operation, the plant Power House provided high pressure process steam, low pressure heating steam, and compressed air for manufacturing use. | |||

By 1915, major substations in the plant were located in, or near, Buildings 4, 12, 15, 41, 42, and 43 on the North Side, and Buildings 26, 32, and 33 on the South Side. In addition, there was a separate set of feeders from the Power House to the main transformer testing facility in Building 12 (because of the large amount of power required by that operation). As a matter of interest, all of the steel buildings in the plant were connected electrically by means of a large diameter copper cable; this, in turn, connected to a grounding plate at the bottom of nearby Silver Lake! The substations served to step down the voltage from the Power House to: 110/220 volts single-phase 440 volts three-phase 550 volts two-phase The three-phase system, as it evolved in the plant, operated at 13,800 volts (13.8-kv). In 1936, switch-gear was installed in the Power House in anticipation of an interconnection between the plant and the lines of "The New England and Turner's Falls Power Company". These were 115-kv lines which terminated at the Silver Lake Station of the Pittsfield Electric Company. Two Pittsfield-built transformers were installed near Silver Lake. These had dual secondary windings. One winding connected with the 13.8-kv three-phase plant power system, while the other winding connected: with the 2300-volt two-phase plant power system (via a phase-changing winding connection). The mercury turbine installation referred to above was the result of development work in the use of mercury vapor as a more efficient alternative to high pressure steam for driving turbines. Complications in the technology, however, led to its eventual abandonment (today, such a concept would probably be unacceptable due to the usage of vast amounts of toxic mercury!). | |||

Revision as of 20:09, 27 January 2011

Preface

Transformers at Pittsfield: A History of the General Electric Large Power Transformer Plant at Pittsfield, Massachusetts, by Thomas J. Blalock

In 1886, William Stanley first successfully demon¬strated the use of the transformer in an alternating current system to provide electric lights for the Town of Great Barrington, Massachusetts.

In 1986, the General Electric Company announced that it would be closing its Large Power Transformer Operation in nearby Pittsfield. The existence of this plant was a direct result of Stanley's work one hundred years before.

The technology associated with the design and manu¬facture of transformers in Pittsfield was sold to the Westinghouse Corporation, which built large transformers at a plant in Muncie, Indiana. However, about a year later, Westinghouse sold its Muncie operation to a for¬eign conglomerate known as "ABB" (ASEA - Brown-Boveri). Thus, one hundred years of transformer technology which had developed in the Berkshires of Western Massachusetts fell, unceremoniously, into foreign hands.

My own involvement with the Pittsfield transformer operation began in 1966 when I joined the High Voltage Laboratory as a Development Engineer. Later, I became a Fortran computer programmer in the Engineering Depart¬ment, working with elaborate development and design pro¬grams having to do with transient voltage distribution in transformer windings and stray magnetic losses in transformer cores.

In 1987, when the Pittsfield transformer plant was closed down, I was employed as a Test Engineer working in Building 100, the cavernous main assembly building for large transformers. As such, I was to witness the somewhat bizarre spectacle of the "slow death" of this formerly bustling facility through the late summer and fall of that year.

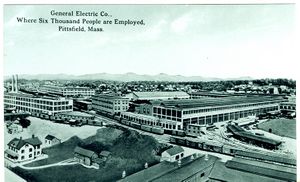

In 1903, when the Stanley Electric Manufacturing Company in Pittsfield first became affiliated with the General Electric Company, it employed about 1700 and the population of Pittsfield was about 25,000. At the peak of employment in the Pittsfield G.E. operation, around 1950, the Pittsfield population had climbed to 53,000; however, the employment in "Transformers" had risen to 10,000!

Thus, General Electric had become a very signifi¬cant factor in the economic and the social fabric of Pittsfield and, indeed, in all of Berkshire County.

During the 1950's, several product lines related to transformers were moved to other locations around the country. This was the result of a vast reorganization and decentralization plan instituted by Ralph Cordiner, then the corporate head of the General Electric Company. As a consequence of this, the manufacture of capacitors was moved to Hudson Falls, New York; small distribution transformers were to be built in Hickory, North Carolina; and medium-sized power transformers were to be manufac¬tured in Rome, Georgia.

A "low point" in the history of transformers in Pittsfield came in 1961 when several high-ranking Gen¬eral Electric executives were caught up in a price-fixing scandal which involved major competitors such as Westinghouse. A real high point, however, was the con¬struction of Building 100, the huge transformer assembly and testing building, in 1968.

The men who headed the Pittsfield Transformer Oper¬ation during its eighty years of existence as a part of General Electric were (their actual titles changed from time to time as the corporate organization changed):

- Cummings C. Chesney

- Edward Wagner

- Louis Underwood

- Robert Paxton

- Francis Fairman

- William Ginn

- Raymond Smith

- Robert Gibson

- Robert Lewis

- Charles Meloun

- Bruce Roberts

- Nicholas Boraski

In 1972, the Company succeeded in obtaining the approval of the labor unions to switch hourly workers from incentive pay to "day rates" as a cost-cutting measure. This cost the average worker about $25.00 per week in lost wages. As a result, a critical drop in productivity led to "red ink" for the Transformer Oper¬ation. However, through the efforts of Bruce Roberts and Nicholas Boraski, the operation was eventually brought back into the black.

That was not enough to save the Transformer Opera¬tion, however. In 1974, the "oil crisis" in this coun¬try caused the traditional seven to eight percent annual increase in electrical power usage to disappear. Thus, the market for new large power transformers essentially vanished. The Pittsfield operation was never able to recover from that blow and, in 1987, with 1900 employees remaining, the General Electric Company decided to end the business of building transformers in Pittsfield.

Because of my background, as well as the nature of the business which is documented here, this historical outline is rather technical in nature. A Glossary of terms is included which serves to explain some of the more generally-used phrases pertinent to the design and manufacture of large power transformers.

This book is an edited version of a manuscript by the author which was prepared during 1995-96, and which is catalogued in the Local History collection of the Berkshire Athenaeum in Pittsfield.

T.J. Blalock Pittsfield, Mass. June, 1997

Acknowledgements

Several professionals formerly associated with the Pittsfield G.E. Transformer Operation provided valuable information, as well as encouragement, for this work. On topics relating to the engineering and design aspects of transformers and related equipment, these included John Church, Bell Cogbill, George Doucette, Harry Mason, Bill McNutt, Bob Mottershead, Al Rowe, George Sauer, Leonard van den Honert, and Don West.

Janice Calderwood provided information and material related to the Distribution Transformer Operation. Ed Kopf contributed valuable information on the early years of the Apprentice Program, as well as on many other as¬pects of life in the Pittsfield plant. William Coles provided details of Power House modifications over the years. Sam Sass contributed historical details related to the Stanley Library and other matters. R. Kelly Niederjohn and Stan Wilk provided information on the aspects of shipping huge transformers.

John Anderson contributed information regarding the Empire State Building lightning study, as well as the operation of the High Voltage Laboratory and Projects EHV and UHV. John Benedict contributed photos and other material related to the Building 9 High Voltage Labora- tory. Details relative to lightning arrester development and the operation of the Dufour cold-cathode oscillograph were provided by Tom Carpenter. Finally, much informa¬tion about the operation of the transformer testing faci¬lity was contributed by G.G. ("Pete") Kemp and by Tom Stanfield.

Access to archival material stored in the Pittsfield G.E. plant was provided by Tom Bednarz, William Carter, Jr., and Art Stringer.

Information taken from issues of the Pittsfield G.E. News and the 'Current News', as well as other archival material, was obtained with the assistance of the staff of the Local History Room of the Berkshire Athenaeum in Pittsfield; special thanks to Ruth Degenhardt in this regard. Postcard views of the early years of the Pitts¬field plant were reproduced from the collection of Judy Rupinski of Pittsfield.

Photographs from the collection of the Hall of Elec¬trical History of the Schenectady Museum Association, Schenectady, New York, were provided with the assistance of staff members John Anderson and Mary Kuykendall.

Also, "spiritual" support on matters relative to the publication of this work was provided by Paul Argentini.

Digital processing of G.E. photographic negatives was by Mark Swirsky of the Photo Shop in Pittsfield, MA.

Special recognition is due the late "Jimmy" Eulian, former High Voltage Laboratory technician, for providing many fascinating reminiscences from his forty-one years of employment in the Pittsfield G.E. plant.

Finally, the author wishes to give special recogni¬tion as well to two highly regarded professionals, now retired, who were very instrumental in the development of his career at the Pittsfield plant: Mr. Al Rohlfs, formerly with the High Voltage Laboratory, and Mr. Ed Uhlig, former Manager of Power Transformer Engineering in Pittsfield.

Chapter 1: The Early Years

"One day Mr. Whittlesey came to Barrington and I told him of my withdrawal from the Pittsburgh company. He asked me to come to Pittsfield and see some of his friends before I embarked anew. I came up to Pittsfield and met two sterling men, the late W.R. Plunkett and the late W.W. Gamwell. Mr. Plunkett called a meeting of bus¬inessmen at his residence on East Street. A dozen or so attended this meeting and we discussed the starting of a company to build transformers. Mr. Whittlesey then got subscriptions for $25,000. Two companies were organized. One, 'The Laboratory Company', with a small capital, in which Messrs. Chesney, Kelly and myself were the princi¬ple stockholders, and the other, 'The Manufacturing Com¬pany'. Mr. Chesney was chosen as the works manager of the manufacturing company and we started in."

William Stanley

The above quotation describes William Stanley's de¬parture from the Westinghouse Company in Pittsburgh, and the subsequent establishment of a transformer manufac¬turing plant in Pittsfield. Thus began the ninety-six year history of the manufacture of transformers in Pitts¬field which ended with the closing of the Large Trans¬former Operation of General Electric in 1987.

The Stanley Laboratory Company originated in a build¬ing on Cottage Row (now Eagle Street) in Pittsfield, in 1890. The Stanley Electric Manufacturing Company went into operation on Clapp Avenue (now gone) in January of 1891. The Works Engineer was Cummings Chesney and the Shop Superintendent was John Kelman. The first shipment of "S.K.C." (Stanley-Kelly-Chesney) transformers left the shop on April 1, 1891.

The last G.E. power transformer cleared "Test" in Building 100 in Pittsfield in October of 1987.

In 1892, the Clapp Avenue works employed sixteen people. Just one year later, a new plant employing 300 people went into operation on Renne Avenue! The Clapp Avenue plant was then used for the manufacture of switchboards.

In 1895, the Stanley Electric Manufacturing Company absorbed the Stanley Laboratory Company. In 1899, a controlling interest in the manufacturing company was sold to John A. Roebling & Sons of Trenton, New Jersey (the builders of the Brooklyn Bridge), and the Stanley Company was reorganized under the corporate laws of the State of New Jersey. F.A.C. Perrine, who was related to the Roeblings by marriage, was named the new president of the company. There was much trepidation in Pittsfield as to whether the company would remain here or not. At this time, William Stanley "retired" and agreed to be a consultant "if needed".

The company did remain in Pittsfield and, in 1900, under the direction of Perrine, construction began for a new plant in the Morningside section of the city. This was the beginning of what would eventually become the sprawling General Electric "main plant" complex. In 1901, the Morningside plant employed 1200 people, and both the Clapp Avenue and the Renne Avenue plants were abandoned.

As mentioned, William Stanley became a "consultant" and went on to pursue other interests. One of his part¬ners, Cummings C. Chesney, became the Works Manager of the Morningside plant. The other partner, John Kelly, eventually quit when his Irish temperament would not allow him to work for a former competitor as the company became a subsidiary of General Electric in 1903.

In that year, General Electric bought a controlling interest in the Stanley Company. At the same time, G.E. bought out the General Incandescent Arc Light Company of New York. These two companies were combined to form the "Stanley - G.I. Company". Once again, there was much trepidation in Pittsfield as to whether the company would remain here or not! However, in 1905, a massive expan¬sion of the Morningside plant was announced.

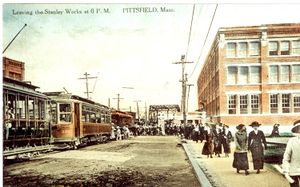

In 1907, the plant became the Pittsfield Works of the General Electric Company and, by 1912, it covered an area which included 1,600,000 square feet of buildings. In 1915, one-sixth of the population of Pittsfield were em¬ployed in the plant, and it produced a total of 4,800,000 "horsepower" in transformers (roughly 3.6 million kilo¬watts worth). Also produced were flat irons, electric fans, and small motors.

According to an article in the October, 1908 issue of the General Electric Review, G.E. decided to use the Pittsfield plant for the manufacture of transformers in 1907 because the area afforded "opportunities for the acquisition of skilled labor of American extraction"!

At first, only small standard transformers (known as Type 'H') were built in Pittsfield; however, in Septem¬ber of 1907, the Lynn (Mass.) Transformer Department was moved to Pittsfield and, by 1908, the Schenectady (N.Y.) transformer operation as well. Thus, in 1908, all G.E. transformers, with the exception of some small specialty types, were being manufactured in Pittsfield and the plant had increased in size by another fifty percent.

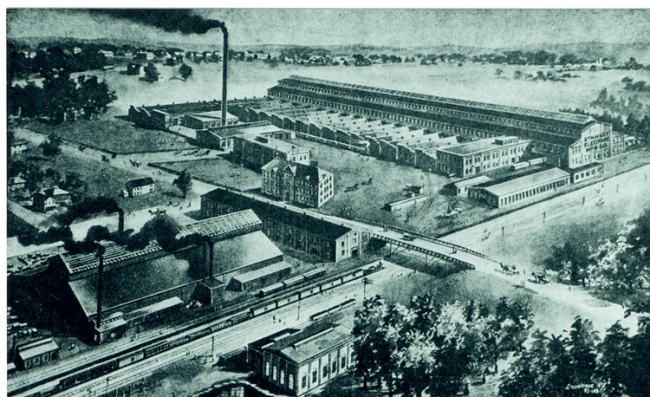

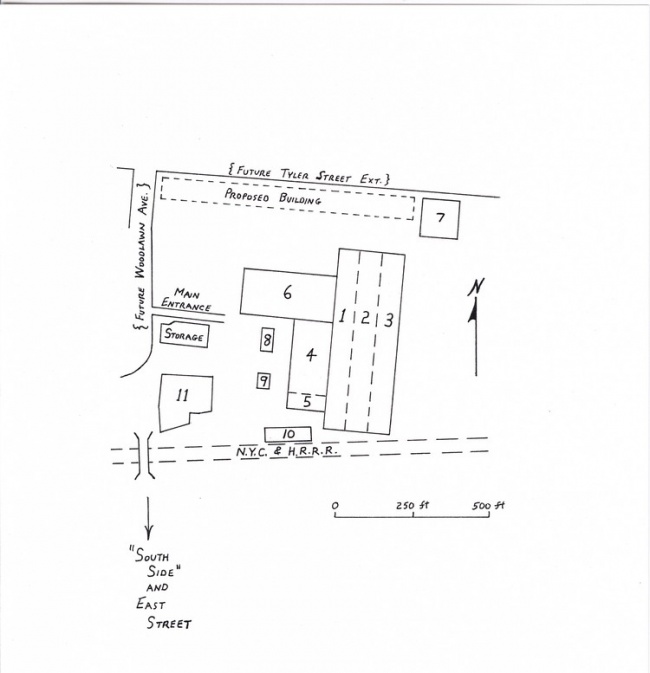

The preceding page shows the building layout of the plant in 1908, just after it became the Pittsfield G.E. Works. The area shown is that located north of the New. York Central and Hudson River Railroad tracks. This was actually the right-of-way for the Boston & Albany Rail¬road, which was owned by the NYC&HRRR. These tracks do still exist, and serve Conrail and Amtrak trains which run between Boston, Mass. and Albany, N.Y.

The identified buildings served the following func¬tions in 1908:

Buildings 1-2-3

These were the main transformer assembly and testing bays. Building 1 was constructed in 1900, and Buildings 2 and 3 were added around the time that the plant became a part of G.E. These buildings still exist today.

Building 4

This was the main winding area for the larger sizes of transformers. It also still exists. This was also the assembly area for small types of transformers.

Building 5.

This was the main shipping area. It was served by a railroad siding running along its south side; this siding also ran through the south end of the Building 1-2-3 complex. This building eventually housed offices and the "copper shop", and still exists.

Building 6

This was the area in which the various types of insulation (such as pressboard, etc.) needed in the transformers was prepared. It still exists.

Building 7

This was where the thin laminations of steel needed to build up the magnetic cores of the transformers were fabricated. This building served several other functions in later years. It still stands, but is somewhat derelict.

Building 8

This was the Laboratory building where the devel¬opment of transformer insulation materials, and the high voltage testing of same, was carried on. It still stands, but is also somewhat derelict.

Building 9

This no longer exists; it was a storage facility for the oils used in transformers for insulation and cooling.

Building 10

This was identified as a Carpenter and Pattern Shop, and no Longer exists.

Building 11

This was the Brass Foundry and Tank Shop, for the production of brass electrical fittings and the fabrication of the iron tanks which held the working parts of the transformers. The site is presently occupied by a new Building 11 dating from the 1960's.

The building near the Main Entrance, designated as "Storage", was soon after replaced by Building 16; this became the main Engineering and Drafting building for the transformer operation. It still stands.

Around this same time (1909-10), an addition known as Building 13 was constructed at the south end of the Building 1-2-3 complex; it is now gone. Also, a new Tank Shop (Building 14) was constructed to the east of Building 7, and a new shop for core steel (Building 15) was added to the north of Buildings 4 and 6. In 1914, a larger transformer assembly and testing facility known as Building 12 was begun to the east of Building 3. All of these latter buildings still exist.

Also, the area designated as "Proposed Building" became Building 17. Originally, this also served as a Tank Shop; however, for many years after that, it was the main winding facility where most of the large trans¬former windings were constructed on winding "lathes". This building still stands.

In 1908, the major buildings on the "South Side" of the railroad tracks were:

- an iron foundry, using cupola-type melting furnaces, for the production of cast iron transformer tanks (in later years, the tanks would be made of welded steel plates). This was on the site of the present Building 33.

- a building for producing molded-type insula¬tions, and a building for the kiln-drying of wood insulation materials.

- a building for the manufacture of fan motors. This became the site of Building 26 which was razed in 1988.

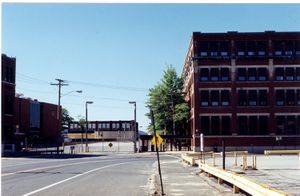

- the original Power House for the plant. This became Building 31 which still stands, but is now derelict.

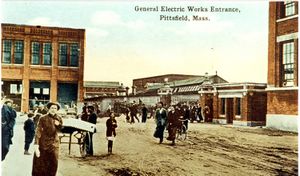

The 1908 layout of the "North Side" of the plant shows a curve in the street line to the north of the railroad bridge. Eventually, this became the inter¬section of Woodlawn Avenue and Kellogg Street. Also, this became the site of the "North Gate", a new main entrance to the plant.

The establishment of North Gate coincided with the construction of a main office building, Building 42, in 1911. This building was directly across from (to the west of) Building 11. Two years later, an addition was constructed running west along Kellogg Street. This was known as Building 43 and contained more office space. Both Buildings 42 and 43 still exist, but are unused.

Along with the main offices for the plant, there was some production area in Building 42; this was mainly devoted to the manufacture of heating devices. Also, there was a Telegraph Office with connections to both the Postal Company and Western Union, along with a line directly to the Schenectady G.E. plant. In addition to offices, Building 43 contained production area devoted to the manufacture of lightning arresters, a tool room, and space for the training of Apprentices.

Chapter 2: The Electric Power System

An interesting aspect of the electric power system in the Morningside plant is that it was not the standard three-phase type of power which is universally used now. The generation and distribution was via a system known as "two-phase".

William Stanley designed and built a great deal of two-phase equipment during the 1890's, partly because of a belief in its superiority over three-phase, but also to avoid patent infringement problems with General Electric and Westinghouse who both used the three-phase system.

In fact, three-phase is decidedly superior for power distribution purposes. Thus, the old two-phase systems have gradually faded out of existence. However, two-phase power was so firmly entrenched in the Pittsfield plant that remnants of it still exist today! This has to do with the existence of old two-phase motors which have never been replaced.

Three-phase power consists of three alternating-type voltages intermingled on three wires. It can be proven mathematically that it is the most efficient system for transferring large amounts of electric power from one place to another, considering the weight of copper which is necessary to do so.

However, in the early 1890's, the understanding of the complexities of "polyphase" (more than one phase) systems was still limited. In particular, there were problems in learning how to regulate the three voltages in a three-phase system in order to keep them all at a constant level. Varying voltage levels severely reduced the expected life of the early incandescent lamps.

Since the basic two-phase system consisted of two completely separate two-wire single-phase circuits, independent regulation of each circuit was relatively simple. This was the main reason that Stanley, as well as others, advocated the use of the two-phase system.

The two-phase system which was adopted in the plant in Pittsfield was somewhat unusual in that only three wires were used instead of four; one wire served as a common for the two single-phase circuits. The two voltages in a two-phase system are at ninety electrical degrees to each other.

Thus, when one wire is used as a common return, the current which flows in it is 41 percent greater than the current in the other two wires, even when feeding a balanced load such as a motor.

Because of this, feeder cable runs in the plant often consisted of two cables of one size plus a third cable which was roughly fifty percent larger in cross-section. However, sometimes it was apparently easier to deal with just one size of cable; in such situations, four cables were run and two were paralleled to use as the common. Obviously, this led to some waste in the total amount of copper used.

The original plant Power House dated from 1900 when the Stanley Company moved from Renne Avenue and Clapp Avenue in Pittsfield. The first generators installed were two-phase machines. By 1950, there were still a couple of two-phase generators (of later vintage) being held in reserve for emergencies. However, the active generation by that time was all three-phase. Over the years, phase-changing transformers had' been installed in some of the electrical substations around the plant to provide two-phase power to old motors still in use. As of today (1997), there are still one or two of these special transformers in use for this same purpose!

The windings of the phase-changing transformers were of a special design developed by G.E. engineers which would have allowed the transformers to be converted to straight three-phase transformers at some pertinent time. Doubtless, these engineers would have been surprised if they knew that such a changeover was destined never to happen!

The two-phase generation and distribution voltage was originally chosen to be 2300 volts, and this was never changed through the years. In 1900, and for some years after that, all of the generators in the Power House were belt-driven from reciprocating steam engines. In later years, of course, the old engines were slowly replaced by steam turbines, and the generators replaced by more modern designs.

The Power House was erected near to Silver Lake, so as to have an adequate supply of cooling water for condensing the steam. Eventually, this became known as Building 31.

Synopsis of Power House History

- 1900 - original power house constructed

- 1907, 08 - two 500-kw, two-phase vertical turbines installed

- 1910, 11 - two 1500-kw, two-phase four-stage turbines installed

- 1915 - 2500-kw, two-phase horizontal turbine installed

- 1930's - experimental mercury turbine installed

- 1941 - 3000-kw, two-phase horizontal turbine installed

- 1946 - two 7500-kw, three-phase horizontal turbines installed

- 1950 - 7500-kw, three-phase mercury turbine installed

- 1960 - mercury turbine removed

- 1970 - power house ceases generation; provides steam only

For some time prior to 1970, General Electric had a cogeneration agreement with the Western Massachusetts Electric Company whereby they purchased any excess power available from the Power House.

During the 1980's, it was determined that the Power House could not be brought up to existing pollution standards. Accordingly, G.E. instigated the construction of a new cogeneration plant on property which they owned to the east of the main plant. The plant Power House was then completely shut down. Today, the new plant sells electric power to Northeast Utilities, and sells steam for heating purposes to General Electric.

When in full operation, the plant Power House provided high pressure process steam, low pressure heating steam, and compressed air for manufacturing use.

By 1915, major substations in the plant were located in, or near, Buildings 4, 12, 15, 41, 42, and 43 on the North Side, and Buildings 26, 32, and 33 on the South Side. In addition, there was a separate set of feeders from the Power House to the main transformer testing facility in Building 12 (because of the large amount of power required by that operation). As a matter of interest, all of the steel buildings in the plant were connected electrically by means of a large diameter copper cable; this, in turn, connected to a grounding plate at the bottom of nearby Silver Lake! The substations served to step down the voltage from the Power House to: 110/220 volts single-phase 440 volts three-phase 550 volts two-phase The three-phase system, as it evolved in the plant, operated at 13,800 volts (13.8-kv). In 1936, switch-gear was installed in the Power House in anticipation of an interconnection between the plant and the lines of "The New England and Turner's Falls Power Company". These were 115-kv lines which terminated at the Silver Lake Station of the Pittsfield Electric Company. Two Pittsfield-built transformers were installed near Silver Lake. These had dual secondary windings. One winding connected with the 13.8-kv three-phase plant power system, while the other winding connected: with the 2300-volt two-phase plant power system (via a phase-changing winding connection). The mercury turbine installation referred to above was the result of development work in the use of mercury vapor as a more efficient alternative to high pressure steam for driving turbines. Complications in the technology, however, led to its eventual abandonment (today, such a concept would probably be unacceptable due to the usage of vast amounts of toxic mercury!).