Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== Anne Morrow Lindbergh == | == Anne Morrow Lindbergh == | ||

[[Image:Anne Morrow Lindbergh.jpg|thumb|right|Anne Morrow Lindbergh. Courtesy: Smithsonian Institution.]] | |||

Born: 22 June 1906 | |||

Died: 07 February 2001 | |||

She | Anne Morrow was born into luxury on 22 June 1906 in Englewood, New Jersey, the daughter of U.S. Senator Dwight Morrow. She attended college, still something of a rarity for women in that day, graduating from elite Smith College in 1928. Less than two years later, she married airplane pilot Charles Lindbergh, who had risen to international fame in 1927 by becoming the first person to fly alone, non-stop, across the Atlantic Ocean. | ||

The Lindberghs' first married years were spent together doing Charles’ work, which involved surveying potentially commercial air routes. The work took them around the world: over Africa, South America, and Asia. Anne acted as Lindbergh’s co-pilot, navigator, and radio operator. | |||

She also described the difficulties of operating the radio equipment of the day. Changing frequencies was not as simple as turning a dial, but was accomplished by manually plugging one of a series of small wire coils into a socket on the transmitter. She wrote, | She described one of her experiences in detail in her book, Listen, The Wind (one of several books she wrote over the years). While flying, she often had to take down incoming radio telegraph messages. She recalled that: | ||

<blockquote>“at the same time, I had to keep a pad balanced on my lap for taking down messages. Receiving was still quite difficult. Except for familiar words and expressions, I could not yet translate the messages in my head and was forced to write them letter by letter as the sounds came to my ear. My pencil and not my mind apparently did the translating, hopping busily across the page. When the pencil stopped I would look down and see what had been written. . .” </blockquote> | |||

She also described the difficulties of operating the [[Radio|radio]] equipment of the day. Changing frequencies was not as simple as turning a dial, but was accomplished by manually plugging one of a series of small wire coils into a socket on the transmitter. She wrote, | |||

“at the right side of the seat, out of sight but well within reach, was the box for the transmitter coils. The transmitter itself, a square block box, mounted like the receiver was in front of me on my left. Its door let down and formed a convenient ledge for the coils as I was changing them. Then there was the antenna reel on the floor below this, its copper wire running down through a hole in the floor boards. When we took off, this was wound up tightly, the ball-weight on the end pulled snugly against the outside of the fair-lead. But once we were up, it trailed in the air behind us. . .” | <blockquote>“at the right side of the seat, out of sight but well within reach, was the box for the transmitter coils. The transmitter itself, a square block box, mounted like the receiver was in front of me on my left. Its door let down and formed a convenient ledge for the coils as I was changing them. Then there was the antenna reel on the floor below this, its copper wire running down through a hole in the floor boards. When we took off, this was wound up tightly, the ball-weight on the end pulled snugly against the outside of the fair-lead. But once we were up, it trailed in the air behind us. . .”</blockquote> | ||

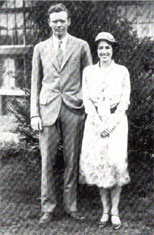

[[Image:Annelind.jpg|right]] | [[Image:Annelind.jpg|thumb|right]] | ||

She worked in the dark to avoid putting reflections on the windshield: | |||

<blockquote>“I ran my fingers over the coils, found the right ones, jiggled them out of the their places and pressed them (smelling faintly of shellac) into their sockets in the transmitter box. I clamped down the earphones over my ears. I switched on the receiver. The luminous dials glowed warmly out of the dark. I reached for the plump handle of the antenna reel. I put my fingers on the smooth key. 'Darr dit darr dit, dit darr dit -' my work had begun. Outside the night rushed by...” </blockquote> | |||

The Lindbergh’s survey of parts of Asia was cut short in late 1931 when Anne’s father died. If they had not subsequently sailed back to New Jersey, they might have not been home when tragedy struck the family in March 1932. Their son Charles, Jr., was kidnapped. An intense search held the attention of millions of people around the world. Sadly, the infant was found dead ten weeks later. A carpenter named Richard Hauptman was convicted and later executed for the crime. | The Lindbergh’s survey of parts of Asia was cut short in late 1931 when Anne’s father died. If they had not subsequently sailed back to New Jersey, they might have not been home when tragedy struck the family in March 1932. Their son Charles, Jr., was kidnapped. An intense search held the attention of millions of people around the world. Sadly, the infant was found dead ten weeks later. A carpenter named Richard Hauptman was convicted and later executed for the crime. | ||

Still grieving, the Lindberghs took off in May of the following year to complete a five-month aerial survey of Asia, for which the National Geographic Society awarded Anne a medal in 1934. She spent much of her later career writing books, and died 7 February 2001. | Still grieving, the Lindberghs took off in May of the following year to complete a five-month aerial survey of Asia, for which the National Geographic Society awarded Anne a medal in 1934. She spent much of her later career writing books, and died 7 February 2001. | ||

[[Category:Communications|Lindberg]] [[Category:Telegraphy|Lindberg]] [[Category:Radio telegraphy|Lindberg]] [[Category:Transportation|Lindberg]] [[Category:Vehicles|Lindberg]] [[Category:Aircraft|Lindberg]] [[Category:Components, circuits, devices & systems|Lindberg]] [[Category:Electronic components|Lindberg]] [[Category:Coils|Lindberg]] [[Category:News|Lindberg]] | |||

[[Category: | [[Category:News]] | ||

Revision as of 20:31, 5 January 2012

Anne Morrow Lindbergh

Born: 22 June 1906

Died: 07 February 2001

Anne Morrow was born into luxury on 22 June 1906 in Englewood, New Jersey, the daughter of U.S. Senator Dwight Morrow. She attended college, still something of a rarity for women in that day, graduating from elite Smith College in 1928. Less than two years later, she married airplane pilot Charles Lindbergh, who had risen to international fame in 1927 by becoming the first person to fly alone, non-stop, across the Atlantic Ocean.

The Lindberghs' first married years were spent together doing Charles’ work, which involved surveying potentially commercial air routes. The work took them around the world: over Africa, South America, and Asia. Anne acted as Lindbergh’s co-pilot, navigator, and radio operator.

She described one of her experiences in detail in her book, Listen, The Wind (one of several books she wrote over the years). While flying, she often had to take down incoming radio telegraph messages. She recalled that:

“at the same time, I had to keep a pad balanced on my lap for taking down messages. Receiving was still quite difficult. Except for familiar words and expressions, I could not yet translate the messages in my head and was forced to write them letter by letter as the sounds came to my ear. My pencil and not my mind apparently did the translating, hopping busily across the page. When the pencil stopped I would look down and see what had been written. . .”

She also described the difficulties of operating the radio equipment of the day. Changing frequencies was not as simple as turning a dial, but was accomplished by manually plugging one of a series of small wire coils into a socket on the transmitter. She wrote,

“at the right side of the seat, out of sight but well within reach, was the box for the transmitter coils. The transmitter itself, a square block box, mounted like the receiver was in front of me on my left. Its door let down and formed a convenient ledge for the coils as I was changing them. Then there was the antenna reel on the floor below this, its copper wire running down through a hole in the floor boards. When we took off, this was wound up tightly, the ball-weight on the end pulled snugly against the outside of the fair-lead. But once we were up, it trailed in the air behind us. . .”

She worked in the dark to avoid putting reflections on the windshield:

“I ran my fingers over the coils, found the right ones, jiggled them out of the their places and pressed them (smelling faintly of shellac) into their sockets in the transmitter box. I clamped down the earphones over my ears. I switched on the receiver. The luminous dials glowed warmly out of the dark. I reached for the plump handle of the antenna reel. I put my fingers on the smooth key. 'Darr dit darr dit, dit darr dit -' my work had begun. Outside the night rushed by...”

The Lindbergh’s survey of parts of Asia was cut short in late 1931 when Anne’s father died. If they had not subsequently sailed back to New Jersey, they might have not been home when tragedy struck the family in March 1932. Their son Charles, Jr., was kidnapped. An intense search held the attention of millions of people around the world. Sadly, the infant was found dead ten weeks later. A carpenter named Richard Hauptman was convicted and later executed for the crime.

Still grieving, the Lindberghs took off in May of the following year to complete a five-month aerial survey of Asia, for which the National Geographic Society awarded Anne a medal in 1934. She spent much of her later career writing books, and died 7 February 2001.