|

|

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| == Amateur Radio == | | == RCA Mark I and Mark II Synthesizers == |

|

| |

|

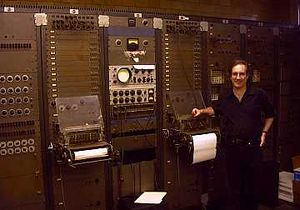

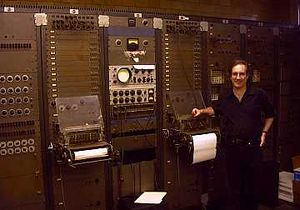

| [[Image:Amatuerradiostamp.jpg|thumb|left]] | | [[Image:RCA Mark II.jpg|thumb|right|RCA Mark II Sound Synthesizer (designed by Herbert Belar and Harry Olson at RCA Victor)]] |

|

| |

|

| A retired military officer in North Carolina makes friends over the radio with an amateur radio operator (known the world over as “hams”) in Lithuania. An Ohio teenager uses her computer to upload a chess move to an orbiting space satellite, where it’s retrieved by a fellow chess enthusiast in Japan. In California, volunteers save lives as part of their involvement in an emergency communications network. And at the scene of a traffic accident on a Chicago freeway, a ham calls for help by using a pocket-sized hand-held radio.

| | In the 1950s, Radio Corporation of America (RCA) was one of the largest manufacturers of consumer entertainment devices and military electronics. For a brief time, RCA was also the site of cutting-edge research in musical instruments, thanks to engineer Harry F. Olson, RCA’s leading expert in the field of acoustics. In the 1940s Olson became interested in making electronic music, and he, along with fellow RCA engineer Herbert Belar, designed a massive [[Electronic Music Synthesizer|electronic music synthesizer]] called the Mark I. |

|

| |

|

| This unique mix of fun, public service, and convenience is the distinguishing characteristic of amateur radio. Some hams are attracted to the idea of communicating across the country, around the globe, and even with astronauts on space missions. Others enjoy building and experimenting with electronics. Although hams get involved in the hobby for many reasons, all have a basic knowledge of radio technology, regulations, and operating principles and must pass an examination for a license to operate on radio frequencies known as the amateur bands. [[Image:Amateur_radio_78.jpg|thumb|right|A pair of 7800's]]

| | <p>While electronic musical instruments, such as the Theremin, had been created before, the RCA Mark I was much more complex. It used a bank of 12 oscillator circuits, which used electron tubes to generate the 12 basic tones of a musical “scale.” These basic sounds could be shaped in virtually limitless ways by passing them through other electronic circuits, including high-pass filters, low-pass filters, envelope filters, frequency dividers, modulators and resonators. Never mind the details of how all these circuits work—the end result was that the Mark I could take those 12 basic notes and reshape them into any imaginable sound. At least in theory. In practice, it was easy to create weird, unearthly sounds, and to imitate certain kinds of existing musical instruments but almost impossible to imitate other sounds like human voices or the smooth transitions between notes on a violin or trombone. Still, the Mark I, demonstrated in 1955, was impressive. It was “played” by laboriously programming a sequence of notes to be played, along with information about how the sound of each note was to be shaped, by punching holes into a long roll of paper, similar to the kind used on a player piano. When all that was prepared, the roll was fed into the machine, the holes read, and music produced. </p> |

|

| |

|

| Amateur radio is as old as radio itself. Not long after Italian experimenter Guglielmo Marconi transmitted the [[Morse Code|Morse Code]] letter “s” from Wales to Newfoundland, Canada in 1901, amateur experimenters throughout the world were trying out the capabilities of the first [[Spark Transmitter|“spark gap” transmitters]]. In 1912 Congress passed the first laws regulating radio transmissions in the United States. By 1914 amateur experimenters were communicating nationwide, and setting up a system to relay messages from coast to coast. In 1927 Congress created the precursor agency to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and specific frequencies were assigned for various uses, including ham bands.

| | <p>The success of the Mark I led to the creation of the Mark II, which had twice as many tone oscillators and gave the composer more flexibility. In 1957, RCA provided the Mark II to a new consortium between Princeton and Columbia Universities to create the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center. This Center would remain a gathering point for musicians and composers interested in synthesizers for many years. One of the most famous works composed for the RCA Mark II was Charles Wuorinen’s “Time Enconium,” of 1968. The Mark II is still in existence, and is located at the Computer Music Center (successor to the Columbia-Princeton center) in New York.<br> </p> |

|

| |

|

| If you were to look at the dial on an old AM radio you’d see frequencies marked from 535 to 1605 kilohertz (kHz). Imagine that band extended out many thousands of kilohertz, and you’ll have some idea of how much additional radio spectrum is available for amateur, government, and commercial radio bands. It is here you’ll find aircraft, ship, fire and police communication, as well as the so-called “shortwave” stations, which are worldwide commercial and government broadcast stations from the U.S and overseas. Amateurs are allocated nine basic “bands” (i.e,. groups of frequencies) in the High Frequency (HF) range between 1800 and 29,700 kHz, and another seven bands in the Very High Frequency (VHF) and Ultra High Frequency (UHF) ranges. There are nine more segments in the Super High Frequency (SHF) and Extremely High Frequency (EHF) microwave bands. Finally, hams can use any frequency above 300 gigahertz (GHz)!

| | == Demonstration == |

|

| |

|

| | <p><flash>file=RCA2.swf|width=682|height=410|quality=best</flash> </p> |

|

| |

|

| | == The Story of the RCA Synthesizer == |

|

| |

|

| Given the right frequency and propagation conditions, amateur radio conversations can take place across town and around the world. Those with a competitive streak enjoy amateur radio contests, where the object is to see how many hams they can contact in a certain time, often a weekend. Some like the convenience of a technology that gives them portable communication. Others use it to open the door to new friendships over the air or through participation in one of thousands of amateur radio clubs throughout the world.

| | {{#widget:YouTube16x9|id=rgN_VzEIZ1I</youtube> |

|

| |

|

| == Governing Bodies ==

| | [[Category:Engineering and society]] |

| | | [[Category:Leisure]] |

| Amateur radio is largely governed globally by the [[International Amateur Radio Union|International Amateur Radio Union (IARU)]], a representative body in the ITU. The IARU comprises representatives from each of the national bodies, eg ARRL in the US, WIA in Australia, PZK in Poland, SARTS in Singapore, MARTS in Malaysia, JARL in Japan, NZART in New Zealand. [and more].

| | [[Category:Music]] |

| | |

| Individual PTT's directly regulate licensing in each Country, examples are FCC (in the USA), ACMA (Australia), Post Office (Solomon Islands), [and more ].

| |

| | |

| Licensing in the United States began with the [[Radio Act of 1912]].

| |

| | |

| == Spinoffs ==

| |

| | |

| There have been some amazing business spinoffs generated by amateur radio enthusiasts, the [[Electron (or Vacuum) Tubes|vacuum tube]] manfacturer [[Eimac|Eimac]], ICOM, Yaesu, Codan and probably others. See the [[Hy-Gain_TH7DX_Antenna_History|Hy-gain TH7DX]] antenna story.

| |

| | |

| Additionally there have been some remarkable explorations into communications, eg, EME Communications, super low bandwidth communications (approx 6Hz channel bandwidth) , eg WSJT, PSK31 (approx 50hz channel bandwidth), etc.

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Amateur radio basic.jpg|thumb|right|A basic ham station used in a field day portable capacity.]]

| |

| | |

| == Amateur Radio Callsigns ==

| |

| | |

| [[Callsign History - Australia|AUSTRALIA]]

| |

| | |

| INDIA - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amateur_radio_callsigns_of_India

| |

| | |

| USA - http://earlyradiohistory.us/recap.htm<br>

| |

| | |

| == EMR Safety Calculator / RF Safety Calculator ==

| |

| | |

| Amateur Radio operators are required to perform EMR Safety Calculations, that control the safe exposure distances to controlled and uncontrolled radio frequency (or EMF) environments. These safety calculations and resultant compliance requirements have largely become mandatory by most regulators. The operator can be asked to produce these calculations when requested by the regulator. The FCC introduced it in 1997, New Zealand in 2000 and Australia in 2002.

| |

| | |

| *The following spreadsheet replicates <u>ALL</u> the regulators tables / formulas and complex safety distance lookup tables found in both the FCC, New Zealand and Australian requirements. It also covers power levels in excess of that legally permitted, as well as the safety calculation for 60m (5MHz) frequency band (which is not part of any guideline currently). Please read the notes and exclusions in the spreadsheet notes page.

| |

| | |

| [[Media:RF_EMR_Exposure_Compliance_publish_draft5.xls|RF EMR Safety Exposure Calculator]] (xls)

| |

| | |

| This spreadsheet calculator addresses the Amateur Radio Operator RF Safety compliance obligations to the following guidelines/standards:

| |

| | |

| *Australia - Human Exposure to EMR: Assessment of Amateur Radio Stations for Compliance with ACA Requirements, May 2005, version 2.0

| |

| *USA - FCC Sup B to OET B65 Ed97-01

| |

| *New Zealand - NZS2772-1999

| |

| | |

| == Further reading: ==

| |

| | |

| [[First-Hand:It Started with Ham Radio|It Started with Ham Radio]], a First Hand History by Pete Lefferson

| |

| | |

| [[Media:1907_wireless_licence_application.pdf|1907 Wireless Licence application form]] (pdf)<br>[[Media:Amateur_radio_78.jpg|Amateur radio IC-7800's photo]] | |

| | |

| [[Category:Radio_broadcasting]] | |

RCA Mark I and Mark II Synthesizers

RCA Mark II Sound Synthesizer (designed by Herbert Belar and Harry Olson at RCA Victor)

In the 1950s, Radio Corporation of America (RCA) was one of the largest manufacturers of consumer entertainment devices and military electronics. For a brief time, RCA was also the site of cutting-edge research in musical instruments, thanks to engineer Harry F. Olson, RCA’s leading expert in the field of acoustics. In the 1940s Olson became interested in making electronic music, and he, along with fellow RCA engineer Herbert Belar, designed a massive electronic music synthesizer called the Mark I.

While electronic musical instruments, such as the Theremin, had been created before, the RCA Mark I was much more complex. It used a bank of 12 oscillator circuits, which used electron tubes to generate the 12 basic tones of a musical “scale.” These basic sounds could be shaped in virtually limitless ways by passing them through other electronic circuits, including high-pass filters, low-pass filters, envelope filters, frequency dividers, modulators and resonators. Never mind the details of how all these circuits work—the end result was that the Mark I could take those 12 basic notes and reshape them into any imaginable sound. At least in theory. In practice, it was easy to create weird, unearthly sounds, and to imitate certain kinds of existing musical instruments but almost impossible to imitate other sounds like human voices or the smooth transitions between notes on a violin or trombone. Still, the Mark I, demonstrated in 1955, was impressive. It was “played” by laboriously programming a sequence of notes to be played, along with information about how the sound of each note was to be shaped, by punching holes into a long roll of paper, similar to the kind used on a player piano. When all that was prepared, the roll was fed into the machine, the holes read, and music produced.

The success of the Mark I led to the creation of the Mark II, which had twice as many tone oscillators and gave the composer more flexibility. In 1957, RCA provided the Mark II to a new consortium between Princeton and Columbia Universities to create the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center. This Center would remain a gathering point for musicians and composers interested in synthesizers for many years. One of the most famous works composed for the RCA Mark II was Charles Wuorinen’s “Time Enconium,” of 1968. The Mark II is still in existence, and is located at the Computer Music Center (successor to the Columbia-Princeton center) in New York.

Demonstration

<flash>file=RCA2.swf|width=682|height=410|quality=best</flash>

The Story of the RCA Synthesizer

{{#widget:YouTube16x9|id=rgN_VzEIZ1I</youtube>