Chester E. Holifield and RCA Mark I and Mark II Synthesizers: Difference between pages

m (<replacetext_editsummary>) |

m (<replacetext_editsummary>) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== | == RCA Mark I and Mark II Synthesizers == | ||

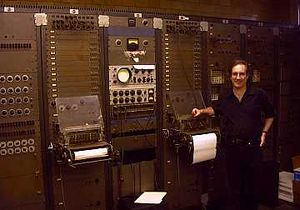

[[Image:RCA Mark II.jpg|thumb|right|RCA Mark II Sound Synthesizer (designed by Herbert Belar and Harry Olson at RCA Victor)]] | |||

In the 1950s, Radio Corporation of America (RCA) was one of the largest manufacturers of consumer entertainment devices and military electronics. For a brief time, RCA was also the site of cutting-edge research in musical instruments, thanks to engineer Harry F. Olson, RCA’s leading expert in the field of acoustics. In the 1940s Olson became interested in making electronic music, and he, along with fellow RCA engineer Herbert Belar, designed a massive [[Electronic Music Synthesizer|electronic music synthesizer]] called the Mark I. | |||

<p>While electronic musical instruments, such as the Theremin, had been created before, the RCA Mark I was much more complex. It used a bank of 12 oscillator circuits, which used electron tubes to generate the 12 basic tones of a musical “scale.” These basic sounds could be shaped in virtually limitless ways by passing them through other electronic circuits, including high-pass filters, low-pass filters, envelope filters, frequency dividers, modulators and resonators. Never mind the details of how all these circuits work—the end result was that the Mark I could take those 12 basic notes and reshape them into any imaginable sound. At least in theory. In practice, it was easy to create weird, unearthly sounds, and to imitate certain kinds of existing musical instruments but almost impossible to imitate other sounds like human voices or the smooth transitions between notes on a violin or trombone. Still, the Mark I, demonstrated in 1955, was impressive. It was “played” by laboriously programming a sequence of notes to be played, along with information about how the sound of each note was to be shaped, by punching holes into a long roll of paper, similar to the kind used on a player piano. When all that was prepared, the roll was fed into the machine, the holes read, and music produced. </p> | |||

<p>The success of the Mark I led to the creation of the Mark II, which had twice as many tone oscillators and gave the composer more flexibility. In 1957, RCA provided the Mark II to a new consortium between Princeton and Columbia Universities to create the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center. This Center would remain a gathering point for musicians and composers interested in synthesizers for many years. One of the most famous works composed for the RCA Mark II was Charles Wuorinen’s “Time Enconium,” of 1968. The Mark II is still in existence, and is located at the Computer Music Center (successor to the Columbia-Princeton center) in New York.<br> </p> | |||

== Demonstration == | |||

<p><flash>file=RCA2.swf|width=682|height=410|quality=best</flash> </p> | |||

== The Story of the RCA Synthesizer == | |||

{{#widget:YouTube16x9|id=rgN_VzEIZ1I</youtube> | |||

[[Category:Engineering and society]] | |||

[[Category:Leisure]] | |||

[[Category:Music]] | |||

[[Category: | |||

[[Category: | |||

Revision as of 21:20, 6 January 2015

RCA Mark I and Mark II Synthesizers

In the 1950s, Radio Corporation of America (RCA) was one of the largest manufacturers of consumer entertainment devices and military electronics. For a brief time, RCA was also the site of cutting-edge research in musical instruments, thanks to engineer Harry F. Olson, RCA’s leading expert in the field of acoustics. In the 1940s Olson became interested in making electronic music, and he, along with fellow RCA engineer Herbert Belar, designed a massive electronic music synthesizer called the Mark I.

While electronic musical instruments, such as the Theremin, had been created before, the RCA Mark I was much more complex. It used a bank of 12 oscillator circuits, which used electron tubes to generate the 12 basic tones of a musical “scale.” These basic sounds could be shaped in virtually limitless ways by passing them through other electronic circuits, including high-pass filters, low-pass filters, envelope filters, frequency dividers, modulators and resonators. Never mind the details of how all these circuits work—the end result was that the Mark I could take those 12 basic notes and reshape them into any imaginable sound. At least in theory. In practice, it was easy to create weird, unearthly sounds, and to imitate certain kinds of existing musical instruments but almost impossible to imitate other sounds like human voices or the smooth transitions between notes on a violin or trombone. Still, the Mark I, demonstrated in 1955, was impressive. It was “played” by laboriously programming a sequence of notes to be played, along with information about how the sound of each note was to be shaped, by punching holes into a long roll of paper, similar to the kind used on a player piano. When all that was prepared, the roll was fed into the machine, the holes read, and music produced.

The success of the Mark I led to the creation of the Mark II, which had twice as many tone oscillators and gave the composer more flexibility. In 1957, RCA provided the Mark II to a new consortium between Princeton and Columbia Universities to create the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center. This Center would remain a gathering point for musicians and composers interested in synthesizers for many years. One of the most famous works composed for the RCA Mark II was Charles Wuorinen’s “Time Enconium,” of 1968. The Mark II is still in existence, and is located at the Computer Music Center (successor to the Columbia-Princeton center) in New York.

Demonstration

<flash>file=RCA2.swf|width=682|height=410|quality=best</flash>

The Story of the RCA Synthesizer

{{#widget:YouTube16x9|id=rgN_VzEIZ1I</youtube>