Alexander Graham Bell: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (15 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

Born: 03 March 1847 <br>Died: 02 August 1922 | Born: 03 March 1847 <br>Died: 02 August 1922 | ||

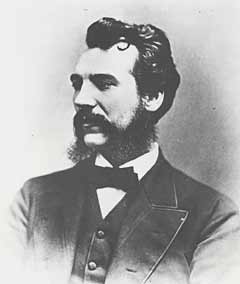

[[Image:Alexander Graham Bell.jpg|thumb| | [[Image:Alexander Graham Bell.jpg|thumb|right|Alexander Graham Bell in 1876]] | ||

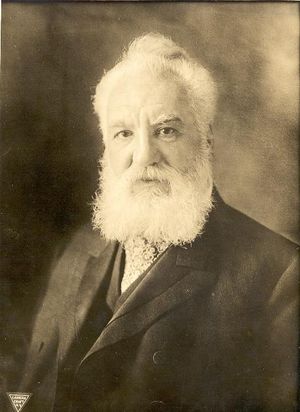

[[Image:Alexander G Bell 0595.jpg|thumb|right]] | |||

[[Image:1560 - Bell Calls Chicago From NYC, 1892.jpg|thumb|right|Alexander Graham Bell in 1892, opening New York-Chicago telephone service]] | |||

“Mr. Watson, come here, I want you.” Alexander Graham Bell spoke these words into his experimental telephone on 10 March 1876. And down the hall, Bell’s assistant, Thomas Watson, heard Bell’s words — the first spoken sentence ever transmitted via electricity. That achievement was the culmination of an invention process Bell had begun at least four years earlier. | |||

In the 1870s, electricity was cutting-edge technology. Like today’s Internet, it attracted bright, young people, such as Bell and Watson, who were only 29 and 22, respectively, in 1876. Electricity offered the opportunity to create inventions that could lead to fame and fortune. | |||

Although Bell had only recently mastered electricity, he had from his youth been an expert on sound and speech. Born and raised in Edinburgh, Scotland, Bell was the son of Eliza and Alexander Melville Bell, a professor of elocution who had devised a technique called visible speech, a set of symbols that represented speech sounds. The elder Bell used the technique to teach the deaf to speak. | |||

In 1863 Bell took the first of what would be many jobs as a speech and music teacher in Scotland. Teaching during the day, he conducted experiments at night on the pitch of vowel sounds using tuning forks. He also became interested in building a machine to produce vowel sounds electronically. He tried to teach himself about electricity, becoming especially fascinated by the growing field of [[Telegraph|telegraph]]. | |||

[[Category: | Young Graham followed in his father’s footsteps, and by the time he was 20, he was teaching visible speech in London. In 1870, after Bell’s two brothers died of tuberculosis, he immigrated with his parents to Canada. The next year, Bell moved to Boston to lecture on visible speech and to teach the deaf. In 1872, he became a professor of elocution at Boston University, where he trained teachers of the deaf and taught private pupils. | ||

Among those pupils were Thomas Sander’s young son, George, and Gardiner Hubbard’s daughter Mabel. Bell impressed both men with his knowledge of electricity, and by 1874 they had agreed to pay his research expenses in return for a share in any inventions Bell might make. He learned how the human ear changes sound waves into actual sound and tried to invent a device to record the rise and fall of the voice in speech. He believed it might be possible to send speech over an electrified wire. When Thomas Watson entered Bell’s life as a skilled electrician who could make devices for inventors, Bell became so obsessed with the electrical transmission of sound that he gave up his teaching job to devote himself completely to the project. | |||

There was already one great electrical industry — the [[Telegraph|telegraph]], whose wires crossed not only the continent but even the [[Transatlantic Cable|Atlantic Ocean]]. The need for further innovations, such as a way to send multiple messages over a single telegraph wire, was well known and promised certain rewards. But other ideas, such as a telegraph for the human voice, were far more speculative. By 1872, Bell was working on both voice transmission and a “harmonic telegraph” that would transmit multiple messages by using musical tones of several frequencies. | |||

The telegraph transmitted information via an intermittent current. An electrical signal was either present or absent, forming the once-familiar staccato of Morse code. But Bell knew that speech sounds were complex, continuous waves. In the summer of 1874, while visiting his parents in Brantford, Ontario, Bell hit upon a key intellectual insight: to transmit the voice electrically, one needed what he called an “induced undulating current.” Or to put it in 21st century terms, what was required was not a digital signal, but an analog one. | |||

Bell still needed to prove his idea with an actual device. He struggled to find time to develop it among competing demands, including his teaching duties and his efforts — pushed by Hubbard — to perfect a multiple telegraph. As Bell was falling in love with Hubbard’s daughter, Mabel, he felt he could ill afford to ignore the older man’s wishes. | |||

On 1 July 1875, Bell succeeded in transmitting speech sounds, albeit unintelligible sounds. On that basis, he began in the fall to draw up patent specifications for “an improvement in telegraphy,” Hubbard filed Bell’s patent application on the morning of 14 February 1876. | |||

There’s a well known tale that Bell beat another inventor, Elisha Gray, to the patent office by a few hours. While true, it’s not the whole story. Bell filed a patent application, a claim that says, in essence, “I have invented.” Gray, on the other hand, filed a caveat, a document used at the time to claim “I am working on inventing.” Priority in American patent law follows date of invention, not date of filing. The U.S. Patent Office issued patent #174,465 to Bell on 7 March 1876. Although court battles over his telephone patents lasted for eighteen years, all cases were eventually resolved in his favor. | |||

Bell returned to his experiments in Boston. On 10 March 1876, he hooked up his latest design, known as the liquid transmitter, into an electrical circuit, and Watson heard Bell’s voice. | |||

Bell announced his discovery, first in lectures to Boston scientists, and then at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. He was largely ignored until Brazilian emperor Dom Pedro II attracted attention to him by listening to Bell reciting Shakespeare over the telephone. The emperor exclaimed, “My God! It talks!” and eminent British physicist William Thomson took news of the discovery across the ocean and proclaimed it “the greatest by far of all the marvels of the electric telegraph.” | |||

Using membrane transmitters, Watson and Bell spoke to each other over rented telegraph wires from points increasingly far apart. Trying to make some quick cash, Bell offered [[Western Union|Western Union]] the patent rights to the telephone for $100,000. The telegraph company had a nationwide network of wires in place and could naturally have branched out. Content with its telegraph monopoly, Western Union turned down Bell’s offer and lost the chance to monopolize another lucrative industry. | |||

By the summer of 1877, the telephone had become a business. The first private lines, which typically connected a businessman’s home and his office, had been placed in service. The first commercial telephone switchboard opened the following year in New Haven. | |||

Bell had little interest in being a businessman. In July 1877, he married Mabel Hubbard, and set out for what proved a long honeymoon in England. He left the growing Bell Telephone Company to Hubbard and Sanders, and went on to a long and productive career as an independent researcher and inventor. In 1880, he invented and patented the photophone, which transmitted voices over beams of light. He also studied sheep breeding, submarines and was close behind the Wright Brothers in the pursuit of manned flight. In Paris in 1880 he was awarded the Volta Prize for scientific achievement. With the prize money, he founded a research laboratory in the United States that worked on projects including metal detectors, [[Phonograph|phonograph]] improvements, and automatic telephone switchboards. The decibel, the unit for measuring the strength of any kind of sound, was named after Bell. | |||

Bell knew the importance of furthering the profession. He attended the organizational meeting of the [[AIEE History 1884-1963|American Institute of Electrical Engineers]] (IEEE’s predecessor society) in May 1884 where he was elected one of six founding vice presidents. And in 1891-92, he served as [[Presidents of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers (AIEE)|AIEE president]]. | |||

Bell also kept a proud eye on the progress of his invention. In 1892, he made the ceremonial call to open long distance telephone service between New York and Chicago, and in 1915 the call to open service between New York and San Francisco. For this occasion, Bell was in New York and his erstwhile assistant Watson was in California. At the request of an attendee, Bell repeated the first words he ever spoke into his invention, “Mr. Watson, come here, I want you. To which, Watson replied from across the continent, “Well, it would take me a week now.” In 1914, Bell was awarded the [[IEEE Edison Medal|Edison Medal]] 'For meritorious achievement in the invention of the telephone.' | |||

Profits from the Bell Company eventually made Bell very wealthy. After 1892 the Bell family lived in both Washington, D.C. and Nova Scotia. Bell never stopped experimenting and inventing. He conducted experiments with flying machines and became a prominent spokesman for the oral method of teaching the deaf to speak and read lips, a method he developed and which is still in use today, although it remains controversial. Although he was not involved in the daily operations of the growing telephone industry, he remained interested in the development of the technology. | |||

Alexander Graham Bell died at his summer home in Baddeck, Nova Scotia on 2 August 1922. During his funeral two days later, every telephone in the United States and Canada went silent for one minute in Bell’s honor. | |||

== Further Reading == | |||

[[Archives:Papers of Alexander Graham Bell|Papers of Alexander Graham Bell]] | |||

[[Category:People and organizations|Bell]] [[Category:Inventors|Bell]] [[Category:Telegraphy|Bell]] [[Category:Electrical telegraphy|Bell]][[Category:Communications|Bell]] [[Category:Telephony|Bell]] | |||

[[Category:Telephony]] | |||

Revision as of 15:59, 5 January 2012

Alexander Graham Bell

Born: 03 March 1847

Died: 02 August 1922

“Mr. Watson, come here, I want you.” Alexander Graham Bell spoke these words into his experimental telephone on 10 March 1876. And down the hall, Bell’s assistant, Thomas Watson, heard Bell’s words — the first spoken sentence ever transmitted via electricity. That achievement was the culmination of an invention process Bell had begun at least four years earlier.

In the 1870s, electricity was cutting-edge technology. Like today’s Internet, it attracted bright, young people, such as Bell and Watson, who were only 29 and 22, respectively, in 1876. Electricity offered the opportunity to create inventions that could lead to fame and fortune.

Although Bell had only recently mastered electricity, he had from his youth been an expert on sound and speech. Born and raised in Edinburgh, Scotland, Bell was the son of Eliza and Alexander Melville Bell, a professor of elocution who had devised a technique called visible speech, a set of symbols that represented speech sounds. The elder Bell used the technique to teach the deaf to speak.

In 1863 Bell took the first of what would be many jobs as a speech and music teacher in Scotland. Teaching during the day, he conducted experiments at night on the pitch of vowel sounds using tuning forks. He also became interested in building a machine to produce vowel sounds electronically. He tried to teach himself about electricity, becoming especially fascinated by the growing field of telegraph.

Young Graham followed in his father’s footsteps, and by the time he was 20, he was teaching visible speech in London. In 1870, after Bell’s two brothers died of tuberculosis, he immigrated with his parents to Canada. The next year, Bell moved to Boston to lecture on visible speech and to teach the deaf. In 1872, he became a professor of elocution at Boston University, where he trained teachers of the deaf and taught private pupils.

Among those pupils were Thomas Sander’s young son, George, and Gardiner Hubbard’s daughter Mabel. Bell impressed both men with his knowledge of electricity, and by 1874 they had agreed to pay his research expenses in return for a share in any inventions Bell might make. He learned how the human ear changes sound waves into actual sound and tried to invent a device to record the rise and fall of the voice in speech. He believed it might be possible to send speech over an electrified wire. When Thomas Watson entered Bell’s life as a skilled electrician who could make devices for inventors, Bell became so obsessed with the electrical transmission of sound that he gave up his teaching job to devote himself completely to the project.

There was already one great electrical industry — the telegraph, whose wires crossed not only the continent but even the Atlantic Ocean. The need for further innovations, such as a way to send multiple messages over a single telegraph wire, was well known and promised certain rewards. But other ideas, such as a telegraph for the human voice, were far more speculative. By 1872, Bell was working on both voice transmission and a “harmonic telegraph” that would transmit multiple messages by using musical tones of several frequencies.

The telegraph transmitted information via an intermittent current. An electrical signal was either present or absent, forming the once-familiar staccato of Morse code. But Bell knew that speech sounds were complex, continuous waves. In the summer of 1874, while visiting his parents in Brantford, Ontario, Bell hit upon a key intellectual insight: to transmit the voice electrically, one needed what he called an “induced undulating current.” Or to put it in 21st century terms, what was required was not a digital signal, but an analog one.

Bell still needed to prove his idea with an actual device. He struggled to find time to develop it among competing demands, including his teaching duties and his efforts — pushed by Hubbard — to perfect a multiple telegraph. As Bell was falling in love with Hubbard’s daughter, Mabel, he felt he could ill afford to ignore the older man’s wishes.

On 1 July 1875, Bell succeeded in transmitting speech sounds, albeit unintelligible sounds. On that basis, he began in the fall to draw up patent specifications for “an improvement in telegraphy,” Hubbard filed Bell’s patent application on the morning of 14 February 1876.

There’s a well known tale that Bell beat another inventor, Elisha Gray, to the patent office by a few hours. While true, it’s not the whole story. Bell filed a patent application, a claim that says, in essence, “I have invented.” Gray, on the other hand, filed a caveat, a document used at the time to claim “I am working on inventing.” Priority in American patent law follows date of invention, not date of filing. The U.S. Patent Office issued patent #174,465 to Bell on 7 March 1876. Although court battles over his telephone patents lasted for eighteen years, all cases were eventually resolved in his favor.

Bell returned to his experiments in Boston. On 10 March 1876, he hooked up his latest design, known as the liquid transmitter, into an electrical circuit, and Watson heard Bell’s voice.

Bell announced his discovery, first in lectures to Boston scientists, and then at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. He was largely ignored until Brazilian emperor Dom Pedro II attracted attention to him by listening to Bell reciting Shakespeare over the telephone. The emperor exclaimed, “My God! It talks!” and eminent British physicist William Thomson took news of the discovery across the ocean and proclaimed it “the greatest by far of all the marvels of the electric telegraph.”

Using membrane transmitters, Watson and Bell spoke to each other over rented telegraph wires from points increasingly far apart. Trying to make some quick cash, Bell offered Western Union the patent rights to the telephone for $100,000. The telegraph company had a nationwide network of wires in place and could naturally have branched out. Content with its telegraph monopoly, Western Union turned down Bell’s offer and lost the chance to monopolize another lucrative industry.

By the summer of 1877, the telephone had become a business. The first private lines, which typically connected a businessman’s home and his office, had been placed in service. The first commercial telephone switchboard opened the following year in New Haven.

Bell had little interest in being a businessman. In July 1877, he married Mabel Hubbard, and set out for what proved a long honeymoon in England. He left the growing Bell Telephone Company to Hubbard and Sanders, and went on to a long and productive career as an independent researcher and inventor. In 1880, he invented and patented the photophone, which transmitted voices over beams of light. He also studied sheep breeding, submarines and was close behind the Wright Brothers in the pursuit of manned flight. In Paris in 1880 he was awarded the Volta Prize for scientific achievement. With the prize money, he founded a research laboratory in the United States that worked on projects including metal detectors, phonograph improvements, and automatic telephone switchboards. The decibel, the unit for measuring the strength of any kind of sound, was named after Bell.

Bell knew the importance of furthering the profession. He attended the organizational meeting of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers (IEEE’s predecessor society) in May 1884 where he was elected one of six founding vice presidents. And in 1891-92, he served as AIEE president.

Bell also kept a proud eye on the progress of his invention. In 1892, he made the ceremonial call to open long distance telephone service between New York and Chicago, and in 1915 the call to open service between New York and San Francisco. For this occasion, Bell was in New York and his erstwhile assistant Watson was in California. At the request of an attendee, Bell repeated the first words he ever spoke into his invention, “Mr. Watson, come here, I want you. To which, Watson replied from across the continent, “Well, it would take me a week now.” In 1914, Bell was awarded the Edison Medal 'For meritorious achievement in the invention of the telephone.'

Profits from the Bell Company eventually made Bell very wealthy. After 1892 the Bell family lived in both Washington, D.C. and Nova Scotia. Bell never stopped experimenting and inventing. He conducted experiments with flying machines and became a prominent spokesman for the oral method of teaching the deaf to speak and read lips, a method he developed and which is still in use today, although it remains controversial. Although he was not involved in the daily operations of the growing telephone industry, he remained interested in the development of the technology.

Alexander Graham Bell died at his summer home in Baddeck, Nova Scotia on 2 August 1922. During his funeral two days later, every telephone in the United States and Canada went silent for one minute in Bell’s honor.