William Fothergill Cooke

Biography

William Fothergill Cooke, along with Charles Wheatstone, professor at King's College, London - was the co-inventor of the Cooke-Wheatstone electric telegraph. A patent was filed in May 1837 and granted on 12 June 1837 for the invention that is the basis for all digital electric communications.

William Fothergill Cooke was born on 4 May, 1806 at Ealing, Middlesex, United Kingdom. William Fothergill was given the first name of his father, William Cooke - a distinguished surgeon who later became appointed professor of anatomy at the University of Durham. William Fothergill Cooke was educated at Durham before going off to the University of Edinburgh. When he attained twenty years of age, Cooke decided to join the Indian Army. [1]

After five years in India attending to his Majesty's service, Cooke left army life and returned home. Following in his father's footsteps, Cooke then went off to study medicine, first in Paris, and then at Heidelberg under Professor Georg Wilhelm Moncke. During his medical studies at Heidelberg, Cooke also took up the study of and making medical wax anatomical models. [2] This allowed William Fothergill Cooke to become a skilled draftsman and a proficient artist of good resolve.

Cooke's sees his first Electric Telegraph

In early 1836 Cooke came to witness a lecture on electromagnetic telegraphy - at the time when telegraph science itself was still only experimental and in its infancy. Dr. Moncke's Heidelberg lecture excited Cooke in that it provided a demonstration of telegraphic apparatus based on the principle introduced by Pavel Schilling [[1]] in 1835. Schilling was inspired by two Germans named Wilhelm Eduard Weber[[2]] and Carl Freidrich Gauss[[3]] It was Weber and Gauss who had at the University of Gottengin, in 1833 two years before, successfully developed the world's first electromagnet telegraph. Essentially this was a digital telegraph actuator. Weber in the Institute of Physics at Gottengin communicated with Gauss, the Professor of Astronomy, at the Observatory at Gottengin. This demonstration was done over telegraph wire strung in the air between the two building locations, and electrically activated with the digital telegraph actuator that the two German professors devised and put into use. The digital action of Gauss and Weber's telegraph is the basis of all electric communications today.

in early 1836, here now three years in following to Gauss and Weber, Cooke became entranced with what he saw during the demonstration of Professor Moncke and decided to put the novel telegraph invention into practical operation. Cooke sought to take it beyond merely the world of academia. Prophetically, Cooke reasoned that the telegraph as such could be applied to the railway systems that in 1836, were just beginning to develop commercially at that time. Cooke saw the potential use of the electric telegraph for the safe regulation of train passage. With this most earnest notion conceived for the public good, Cooke immediately gave up the study of anatomical model making and medicine and advised his parents by letter that he would be soon returning home to merry England.

William Fothergill Cooke left Heidelberg and returned to his native England on 22 April 1836, just as springtime was underway. Cooke soon set about writing up proposals for an electric telegraph, with noble intentions of issuing it as a monograph, but never came to publish.

Cooke's Acquisition of the "NAAMLYST" Journal

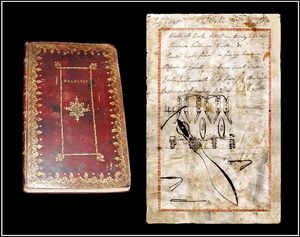

Cooke continued with his writings on the telegraph. In 1836, sometime during his travels, Cooke came to acquire a used, mostly unfinished lavish gold gilt stamped leather bound manuscript journal. [4] The word "NAAMLYST" was prominently stamped into the leather cover.

When Cooke acquired the journal and then opened and saw the array of unfinished "Naamlyst" pages, Cooke's handling of it immediately caught his fancy. Outside of the dark green-blue marbleized end-pages and boards, each page had elaborate patterned borders that were printed 1/4" wide in red ink framing the margin area of each page, top and bottom and to each side. This was somewhat different than the usual blank pages Cooke or anyone usually encountered in journals or books in the time of 1775; when the "Naamlyst" and its binding was first crafted by a book binder of the day. Certainly as well, for Cooke to find this unique journal some sixty-one years later, well after it had begun life in Amsterdam, The Netherlands - was rather significant. It now beckoning before him, and his eyes, for William Fothergill Cooke, the special, even then antiquated journal - would mark a great beginning to the noble quest Cooke had vowed in his mind to accomplish before he left Heidelberg behind him.

This journal had great character, with exquisite calligraphy found in the first swath of pages. The journal had once belonged to an 18th-century societal group, possibly a scientific society that had been based in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. The Dutch word "Naamlyst," in English means simply; 'name list.' Thus, the purpose of the 18th century "Naamlyst" journal was for the recordation of names of personages belonging to the "Amsterdamsche Societiet," the original owner of the journal, and the entity as listed inside the journal on the title page.

The "Amsterdamsche Societiet," as it was called, had been formed on 25 September 1775. This stated and entered on one of the first formally written pages of the journal. The words "Amsterdamsche Societiet" in simply means 'Amsterdam Society' in standard English.

With the remaining leaves of the old journal absent of any entries amounting to well over one hundred or more pages - Cooke would use these, the remaining bulk of empty pages - to enter on and add his own writings and drawings as needed and as thoughts came to him about electric telegraph designs and configurations.

The "Amsterdamsche Societiet" 1775 founding occurred at least three decades before William Fothergill Cooke had been born in 1806, and the defunct society's journal was found by Cooke three decades later, when he was thirty years old; in all, spanning altogether sixty-one years of time.

Initial use of the "Naamlyst" Journal by Cooke

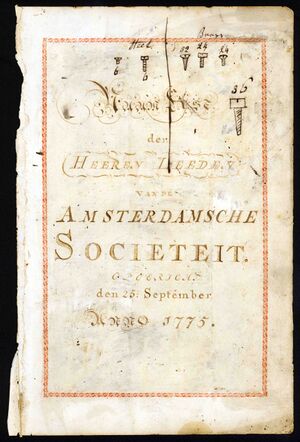

The hand inked title page for "Naam Lyst," the entitled journal - which started off the "Amsterdamsche Societiet" in 1775, would become the first page used by Cooke with any purpose and conviction. At the top of this initial journal page, here Cooke would first come to draw details of basic, varying sized brass or steel screws needed for the telegraph model concepts he was intending to have made. The basis of these concepts Cooke had begun to form in his head after the first spark occurred when he had become witness to Professor Moncke's revelatory Pavel Schilling demonstration at Heidelberg.

The Dutch "Amsterdamsche Societiet" eventually came to be very short-lived, apparently disbanding after the year 1781, just six years approximately past its founding. The Cooke journal bears no entries beyond this time indicating any further reference to the "Amsterdamsche Societiet" or of its members.

The word "NAAMLYST" or essentially a 'name list' or 'list of names' - is boldly stamped in a formal manner on to the journal's reddish-brown leather cover, in gold gilt. This pronouncement was repeated inside the journal in two separate words as "Naam Lyst" - but in the calligraphy form on the initiating 1775 dated "Amsterdamsche Societiet" title page. It was this page on which Cooke would later come to first draw his threaded screw designs as stated above.

One aspect that will never be known, is how and where the "Naamlyst" journal was found and acquired by Cooke during his travels.

The earliest and first dated journal entry in Cooke's hand bears the date of "November 30, 1836." [5] This date is approximately three months before Cooke would, upon an initial recommendation by Professor Michael Faraday and Peter Marc Roget, meet Charles Wheatstone.[[6]] Appointed a Chair in Experimental Physics in 1834 at King's College, London, Wheatstone would help to solidify some of Cooke's telegraph concepts and designs into more workable formulations - leading the way to developing the world's first perfected commercial electric telegraph. A finite understanding by Wheatstone of "Ohms" and "Ohm's Law" contributed greatly to the partnership's progress on the development of the telegraph. Wheatstone as well would be the principal behind solving Cooke's dilemma of long distance telegraph transmission, with the application of a electric relay. Knowledge of the electric relay came to Charles Wheatstone from the American professor named Joseph Henry, who had visited Wheatstone at King's College in 1837.

There are two examples for this 1836 day and date in the journal. One singular page closer to the front bears only a minor title entry, in Cooke's hand, in ink, i.e.: "Astronomy," and the date "November 30, 1836." Nothing is entered below it. The second instance is a more formidable two page entry with exactly the same date and "Astronomy" title as entered by Cooke on the first singular page. This second instance became expanded now in great detail by Cooke.

For some unknown reason Cooke decided to restart the entry treating the same subject entitled "Astronomy" on a different page, separated by several pages past the first paged entry on "Astronomy." This second entry however, comprising now the two full pages, Cooke expanded to incorporate detailed drawings, including a planetary orrery and other astronomical forms. He also denoted a series of lectures numbered one to eight. Also there is mention of a "Dr. Ritchie Theodolite" on the second page, in Cooke's hand, which further chronicles the astronomy lectures documented by Cooke on this date as having most likely been conducted by Professor William Ritchie, the great physicist and doctor who taught astronomy and natural philosophy at the London University.

This earliest dated entry of "November 30, 1836" that is found in Cooke's journal is most significant, as it would be Professor William Ritchie who would become pivotal in Cooke's path towards the completion of his dream of the first perfected commercial electric telegraph. Cooke knew there were others before him, and he had likely heard of the last quarter of the late 18th century and early 19th century electric telegraphic parlor demonstrations by the Swiss inventors Lesage and Jean Alexandre respectively. This 1836 date becomes a further significant benchmark for the manuscript journal "Naamlyst." On one of the frontis leaves, besides on which Cooke has signed his name, not once, but four times, there is, along with the holograph signature of "Proffessor Wheatstone, King's College, London" [[7]] [[8]] the signature of "Proffessor Ritchie" himself - where he further writes: "Proffessor of Natural Philosophy at London University."

This frontis leaf entry, the November 30, 1836 "Dr. Ritchie Theodolite" reference - and other journal references to Prof. Ritchie, historically asserts strong evidence about how Ritchie became Cooke's foundational connection toward suggesting and recommending a person who would become the most important person Cooke would meet outside of Wheatstone. This occurred when Cooke, shortly after arriving back in the United Kingdom in late April 1836, began his initial quest in perfecting the telegraph and taking it to the level of widespread commercial public use.

William Fothergill Cooke introduction to Frederick A. Kerby

It was all at once, just after Cooke had returned to his country-land, that he began making his inquiry into the issue of locating competent craftsmen to do the work from the telegraph designs he was formulating. In some cases, Cooke would come to generate these designs variously on the pages of his used newly acquired "Naamlyst" journal, but not substantially at the onset of his work.

It is interesting to note that what totally crystallized Cooke's interest in the telegraph actually came to him just after the 1836 Moncke demonstration of the Schilling telegraph principles witnessed at Heidelberg. It was while enroute to Frankfort by carriage that Cooke became further inspired: as he intently read Mrs. Somerville's "Connection of the Physical Sciences." As his own letters and writings from this period sent to his mother Mrs. Cooke confirm, once back in London, Cooke immediately sought out proficient machinist and clockmaker practitioners there.

Under the auspices of Latimer Clark, who began his work as an officer in Cooke's Electric Telegraph Company - along with others - The Institution of Electrical Engineers in 1895 would publish Cooke's historic letters to his mother, as a tribute to Cooke. The Institution of Electrical Engineers (IEE) was late the Society of Telegraph Engineers and today, and the society maintains a Internet library online together currently with the Institute of Electric and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): "The world's largest professional association for the advancement of technology."

In the 1830's, at the London University, there was a man by the name of Francis Kerby [9] [10]. Kerby acted as assistant and curator of instruments to both Dr. Dionysius Lardner and Dr. William Ritchie. Francis Kerby himself had been widely published between 1810 and into the 1820's; an authority in his own right giving pertinent discussions on theoretical chemistry.

Frederick A. Kerby [11] a son of Francis Kerby, had become a philosophical and mathematical instrument maker. Although it is not certain if the elder Francis Kerby actually made instruments himself, it is known that he worked for Dr. Ritchie as an assistant, outside of his position as 'curator of instruments' and models at the London University.

Frederick Kerby, as William Fothergill Cooke oft liked to refer, was a "mechanician" by trade. [12] In the year 1836, and at age twenty when Kerby and Cooke met, Frederick A. Kerby had clearly become a "mechanician" of the highest order.

Ritchie's formidable mention and name presence found in the Cooke journal supports that young Kerby was introduced by Dr. Ritchie to Cooke. The time of this introduction between Cooke and Kerby appears to have been earlier than the first dated journal entry of "November 30, 1836" by Cooke, where Cooke references the "Ritchie Theodolite" used and designed by Professor Ritchie for his work in astronomy. The 1836 letters by Cooke to his mother reveal activity mentioning, obtaining and using machinists for telegraph earlier than this first dated entry in Cooke's manuscript journal of "November 30, 1836."

Kerby became one of two main craftsmen Cooke would choose to make his first experimental telegraphs. Moore of Clerkenwell would be the main clock maker who would provide the telegraph clock drive mechanisms for Cooke and his first telegraph instruments.

Most noteworthy, it should be known that Frederick A. Kerby is documented to have [13] made apparatus as early as 1835 for Professor Wheatstone at King's College, London. Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

Unannotated References

Davis, L. J. Fleet Fire: Thomas Edison and the Pioneers of the Electric Revolution (2003). New York: Arcade Publishing.

Vail, J. Cummings (1914). Early History of the Electro-Magnetic Telegraph, from Letters and Journals of Alfred Vail: Arranged by his Son, J. Cummings Vail. New York: Hine Brothers.

Wolfe, Richard J. / Patterson, Richard (2007). Charles Thomas Jackson - "Head Behind The Hands" - Applying Science to Implement Discovery and Invention in Early Nineteenth Century America. Novato, California: Historyofscience.com.

Cooke, William Fothergill (1895). Extracts from the Private Letters of the Late Sir William Fothergill Cooke, 1836 - 39. London: E. and F. N. Spon.

Hubbard, Geoffrey (1965). Cooke and Wheatstone and the Invention of the Electric Telegraph. New York: Augustus M. Kelley.

Cooke, Rev., Thomas Fothergill (1854). The Electric Telegraph: Was it Invented by Professor Wheatstone?. 1. London: W. H. Smith & Son. pp. 170–171.

Cooke, Rev., Thomas Fothergill (1856). The Electric Telegraph: Was it Invented by Professor Wheatstone?. 2. London: W. H. Smith & Son. pp. 165–166 & 170.

AWA (2011 / October). A Dramatic Announcement at the Key and Telegraph Seminar (The AWA Journal). New York: AWA / American Wireless Association.

Weaver, William D. & Potamian, Sci. D, Lond., Brother (1909). Catalogue of the Wheeler Gift of Books,, Pamphlets and Periodicals in the Library of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. New York. American Institute of Electrical Engineers.

External References

Munro, John. "Heroes of The Telegraph".- See Appendix, Chapter III http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/979

Biography of Sir William Fothergill Cooke. Biography from the Institution of Engineering and Technology http://ww38.globusz.com/ebooks/Telegraph/00000023.htm

External Links

^ Lipack, Richard Warren. "Sir William Fothergill Cooke's Newly Discovered Original Notebook / Journal For The World's First Commercial Telegraph" - Curator: Professor Thomas B. Perera, Ph. D. http://www.w1tp.com/cooke/

^ Burns, Bill / Roberts, Steven. "History of the Atlantic Cable & Undersea Communications from the first submarine cable of 1850 to the worldwide fiber optic network: Frederick A. Kerby" http://atlantic-cable.com//Article/Kerby/

^ British Telecom Archives: Events in Telecommunications History, 1846, British Telecom website. http://www.btplc.com/Thegroup/BTsHistory/1846.htm

King's College, London - Archives Catalogues: WHEATSTONE, Sir Charles (1802-1875) - Papers - WHEATSTONE 1: Working papers, experimental notes and correspondence relating to the development of the electric telegraph, [1836-1960] http://www.kingscollections.org/catalogues/kclca/collection/w/10wh20-1/1wh20-a