Radio: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(removed last paragraph) |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== Radio == | == Radio == | ||

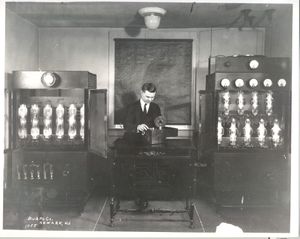

[[Image:RadioEarly.jpg|thumb|right|When it first came on the scene, radio was big stuff—literally. Courtesy: David Sarnoff Library, Princeton, New Jersey.]] | |||

[[Image:4190 - Child listening to early radio.jpg|thumb|right|Child listening to early radio]] | |||

[[Image:Marconi.jpg|thumb|right|Guglielmo Marconi]] | |||

[[Image:1912Radio0058.jpg|thumb|right|A Radio from 1912]] | |||

[[Image:RadioFdr fireside.jpg|thumb|right|President Franklin Delano Roosevelt recognized the power of radio. During the turmoil of the Great Depression and World War II FDR’s “fireside chats” helped soothe a distressed citizenry.]] | |||

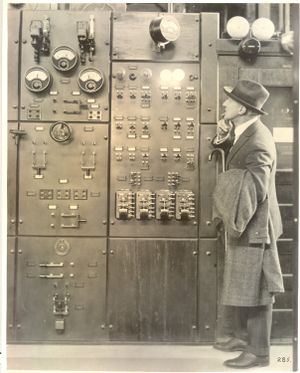

[[Image:ManRadio2nd0054.jpg|thumb|right|Man and Radio]] | |||

[[Image:ManandRadio0053.jpg|thumb|right|Man and Radio]] | |||

For much of the 20th century radio was one of the most popular forms of entertainment. People used to sit on the floor in front of it and listen to programs, much as we watch television today. Indeed, when we think of radio we think of it as the box on which we hear our favorite music or talk shows. | |||

Radio began in 1888 when German physicist [[Heinrich Hertz (1857-1894)|Heinrich Hertz]] demonstrated the existence of radio waves (the unit of measurement for radio wave frequency was named in his honor). [[Radio Waves|Radio waves]], also called electromagnetic waves, have the lowest frequency and the longest wavelength of any type of radiation in the electromagnetic spectrum. In a classroom experiment, Hertz made a condenser that produced these waves. Hertz didn’t think his experiment had any practical applications, but another man did—Italian [[Guglielmo Marconi|Guglielmo Marconi]]. | |||

Marconi thought electromagnetic waves could be used to transmit signals. He was right. At first, Marconi was able to transmit [[Morse Code|Morse Code]] only a couple of miles. But in 1901 he built a transmitter strong enough to send messages across the Atlantic Ocean. This was the beginning of [[Wireless Telegraphy|wireless communication]]. It was even faster than the telegraph and, best of all, no expensive wire or cable had to be laid. | |||

Radio became a new way of sending Morse Code and Marconi created a very successful company that did just that. One of the industries to benefit most from Marconi’s work was the shipping business. Radio operators sent messages to the shore for passengers and in emergencies could be the only hope of contacting rescue ships. | |||

Radio transmission of Morse Code was certainly useful, even life saving, but others began wondering if it could be used to transmit other sounds, such as voice. On Christmas Eve, 1906, Reginald Fessenden proved that it could when [[Milestones:First Wireless Radio Broadcast by Reginald A. Fessenden, 1906|he transmitted the first music and voice program]]. It originated in Massachusetts and was received as far away as Virginia. | |||

While many inventors thought of radio as a substitute for the [[Telegraph|telegraph]] or [[Telephone|telephone]], which transmit information from one point to another point, the fact was that anyone with a radio receiver could listen in on these “private” communications. Pretty soon, the lack of privacy in radio was turned into a benefit. Westinghouse, a company that manufactured radio receivers, decided to set up its own station in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to broadcast information to everyone. Westinghouse was granted the first United States broadcasting license for its station, [[KDKA, First Commercial Radio Station|KDKA]], in October of 1920 and on 2 November 1920 KDKA held the [[Milestones:Westinghouse Radio Station KDKA, 1920|first scheduled public broadcast]]. | |||

As more and more people began listening in to radio broadcasts, inventors sought ways to design better receivers. Using the new technology of electron tubes, engineers introduced more sensitive receiver technology, such as the regenerative and [[Superheterodyne Receiver|superheterodyne circuits]] invented by American Edwin Armstrong. | |||

In addition to being the first to transmit voice over radio, Reginald Fessenden developed amplitude modulation, or as we call it today, AM. AM was a better way to broadcast voice and music than the technologies that came before, which were designed for Morse Code. But AM had problems. The main problem with AM is that the receiver often hears a lot of noise along with the broadcast. The noise comes from sources in the atmosphere like lightning, which is why it is sometimes called static. American inventor Edwin H. Armstrong came up with a different system—[[FM Radio|frequency modulation]], or FM. By the 1930s Armstrong was able to improve the sound quality of radio transmissions by using FM. It would be many more years, however, before ordinary people began listening in. For the time being, AM was still king. | |||

By the 1940s, radio broadcasting was a powerful communications tool and had reached its golden age. The programming on radio was a lot like today’s TV, with news, sports, dramas, comedy shows, and soap operas—not to mention commercials. Just as people today spend their evenings glued to the television, people gathered in their living rooms to listen to the radio. | |||

There were almost no portable radios, except in cars. By the 1930s they were the single most popular item of optional equipment in cars. After the 1947 invention of the [[Transistors|transistor]], however, [[The Transistor and Portable Electronics|radios shrank to the point where they could truly be taken anywhere]]. The transistor also made it possible to combine AM and FM radios (and later [[Cassette Tapes|tape]] and [[Compact Discs (CDs)|CD players]]) into a single, small package. | |||

Despite competition from [[Television|television]] and the Internet, radio remains a major source of information and entertainment. Some radio talk-show hosts have tens of millions of listeners and for many people, radio remains their primary resource for music. | |||

[[Category:Communications]] | |||

[[Category:Radio_communication]] | |||

[[Category:Radio_broadcasting]] | |||

[[Category:Telegraphy]] | |||

[[Category:Wireless_telegraphy]] | |||

[[Category:Fields,_waves_&_electromagnetics]] | |||

[[Category:Electromagnetics]] | |||

[[Category:Electromagnetic_fields]] | |||

Revision as of 20:00, 14 February 2012

Radio

For much of the 20th century radio was one of the most popular forms of entertainment. People used to sit on the floor in front of it and listen to programs, much as we watch television today. Indeed, when we think of radio we think of it as the box on which we hear our favorite music or talk shows.

Radio began in 1888 when German physicist Heinrich Hertz demonstrated the existence of radio waves (the unit of measurement for radio wave frequency was named in his honor). Radio waves, also called electromagnetic waves, have the lowest frequency and the longest wavelength of any type of radiation in the electromagnetic spectrum. In a classroom experiment, Hertz made a condenser that produced these waves. Hertz didn’t think his experiment had any practical applications, but another man did—Italian Guglielmo Marconi.

Marconi thought electromagnetic waves could be used to transmit signals. He was right. At first, Marconi was able to transmit Morse Code only a couple of miles. But in 1901 he built a transmitter strong enough to send messages across the Atlantic Ocean. This was the beginning of wireless communication. It was even faster than the telegraph and, best of all, no expensive wire or cable had to be laid.

Radio became a new way of sending Morse Code and Marconi created a very successful company that did just that. One of the industries to benefit most from Marconi’s work was the shipping business. Radio operators sent messages to the shore for passengers and in emergencies could be the only hope of contacting rescue ships.

Radio transmission of Morse Code was certainly useful, even life saving, but others began wondering if it could be used to transmit other sounds, such as voice. On Christmas Eve, 1906, Reginald Fessenden proved that it could when he transmitted the first music and voice program. It originated in Massachusetts and was received as far away as Virginia.

While many inventors thought of radio as a substitute for the telegraph or telephone, which transmit information from one point to another point, the fact was that anyone with a radio receiver could listen in on these “private” communications. Pretty soon, the lack of privacy in radio was turned into a benefit. Westinghouse, a company that manufactured radio receivers, decided to set up its own station in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to broadcast information to everyone. Westinghouse was granted the first United States broadcasting license for its station, KDKA, in October of 1920 and on 2 November 1920 KDKA held the first scheduled public broadcast.

As more and more people began listening in to radio broadcasts, inventors sought ways to design better receivers. Using the new technology of electron tubes, engineers introduced more sensitive receiver technology, such as the regenerative and superheterodyne circuits invented by American Edwin Armstrong.

In addition to being the first to transmit voice over radio, Reginald Fessenden developed amplitude modulation, or as we call it today, AM. AM was a better way to broadcast voice and music than the technologies that came before, which were designed for Morse Code. But AM had problems. The main problem with AM is that the receiver often hears a lot of noise along with the broadcast. The noise comes from sources in the atmosphere like lightning, which is why it is sometimes called static. American inventor Edwin H. Armstrong came up with a different system—frequency modulation, or FM. By the 1930s Armstrong was able to improve the sound quality of radio transmissions by using FM. It would be many more years, however, before ordinary people began listening in. For the time being, AM was still king.

By the 1940s, radio broadcasting was a powerful communications tool and had reached its golden age. The programming on radio was a lot like today’s TV, with news, sports, dramas, comedy shows, and soap operas—not to mention commercials. Just as people today spend their evenings glued to the television, people gathered in their living rooms to listen to the radio.

There were almost no portable radios, except in cars. By the 1930s they were the single most popular item of optional equipment in cars. After the 1947 invention of the transistor, however, radios shrank to the point where they could truly be taken anywhere. The transistor also made it possible to combine AM and FM radios (and later tape and CD players) into a single, small package.

Despite competition from television and the Internet, radio remains a major source of information and entertainment. Some radio talk-show hosts have tens of millions of listeners and for many people, radio remains their primary resource for music.