Oral-History:Richard Burden

About Richard Burden

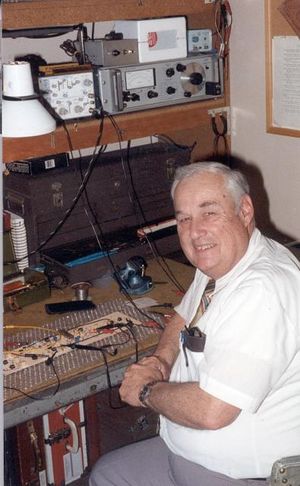

Richard Burden is an independent communications engineer best known for his work in FM and TV stereo systems. After graduating from RCA Institutes in 1952 he taught radar at Fort Monmouth as a civilian and as a corporal, and then served for a year with Armed Forces Radio in New York. After his military service, he worked at General Precision Laboratory until 1960, when he resigned and began work as an independent engineer, working primarily on a variety broadcast systems applications. He has served on a wide variety of radio-related standards committees.

The interview begins with Burden's early interest in science and his early education. He describes his experiences at RCA Institutes and contrasts its electronics curriculum to the power curriculum found in most colleges at that time. He discusses his work at Fort Monmouth and at Armed Forces Radio, and mentions security problems that received attention during the McCarthy era. He briefly discusses his work at GPL and his own interest in hi-fi recording and FM. He then describes in detail his work with Bill Halstead in creating and demonstrating a proposed FM system as members of the National Stereo Radio Committee. After outlining the typical work he would do for a broadcaster as an independent engineer, Burden describes his participation in several other standards-related committees, including the Ad Hoc Committee for the Study of Television Sound in 1973 and the Radio Systems Committee in 1980.

He discusses the problems involved in improving AM performance. He explains his move from New York to California by describing the radio system he and Bill Halstead designed for the Los Angeles airport and the FCC's consequent request that Burden remain in California to provide the Commission with data on the system; his description of the system overlaps with his assessment of the opportunities AM radio provides for similar systems. The interview concludes with Burden's descriptions of his activities in the Audio Engineering Society, the Society for Broadcast Engineers, and IEEE, and how those activities have fit with his advocacy for continuing education for engineers and for outreach to prospective engineering students.

About the Interview

Richard Burden: An Interview Conducted by Frederik Nebeker, Center for the History of Electrical Engineering, November 17, 1995

Interview #240 for the Center for the History of Electrical Engineering, The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc. and Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey

Copyright Statement

This manuscript is being made available for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the IEEE History Center. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of IEEE History Center.

Request for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the IEEE History Center Oral History Program, Rutgers — the State University, 39 Union Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901-8538 USA. It should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

Richard Burden, an oral history conducted in 1995 by Frederik Nebeker, IEEE History Center, New Brunswick, NJ, USA.

Interview

INTERVIEW: Richard Burden

INTERVIEWER: Frederik Nebeker

PLACE: Canoga Park, California

DATE: November 17, 1995

Childhood and Education

Nebeker:

I'm talking with Richard Burden, in Canoga Park, California. This is Rik Nebeker on the 17th of November, 1995. Could I ask you first, where and when you were born, and about your family?

Burden:

I was born in Mount Kisco, New York — that's in Westchester County, just north of New York City — on August 4, 1931.

Nebeker:

In the depths of the Depression.

Burden:

Yes. My mom and dad were both schoolteachers.

Nebeker:

At what level?

Burden:

My dad was in physical education, and my mom was an elementary school teacher.

Nebeker:

Were those hard times in the 1930s?

Burden:

Yes, actually, they were. But I don't remember the early 1930s so well. I do remember at the age of nine, we built our own home. It was done primarily during the summer. I helped. There were little spots in the house that I did. It was just kind of fun for a kid of nine. Dad had bought a piece of property almost across the street from the school. Before, we were a few miles away. That was good timing: we finished the home in 1939, and the war came in 1941, with gas rationing. Since walked to most places, we did pretty well.

Nebeker:

I see. What about your interests as a kid?

Burden:

Well, I had two parallel paths. I enjoyed sports, and I enjoyed radio and electronics.

Nebeker:

You got into amateur radio?

Burden:

I never got into amateur radio. I've built lots of amateur transmitters and stuff for people. But I never got my code speed up. I was working on that when Uncle Sam put his arm around my shoulders and said, "Join me for active duty." I was in the reserves. So I never completed my code.

Nebeker:

So as a kid you built crystal radios?

Burden:

Sound systems and stuff like that. I got involved with little P.A. systems and the like. Doing the sound for plays and stuff at school really got me going. I had a friend and we switched off: one time he'd do the lights and I'd do the sound, and the next time I'd do the lights and he'd do the sound.

Nebeker:

This is in high school?

Burden:

This is in high school. So my interests grew out of that. I had a wire recorder in those days.

Nebeker:

Is that right? Was that commercially produced?

Burden:

It was a Webcorder. I also had a small lathe that would cut acetates, and I built my own amplifier for that. I cut acetates, which turned out to be kind of useful years later, because I got my first job in radio because I could cut acetates. This was the later 1940s, early 1950s, and although tape recorders were out, they weren't down to the level of the small radio stations. When you did commercials and stuff, they were still put on disks.

Nebeker:

I see. And how did you get started, what was the motivation for cutting acetates originally?

Burden:

I was interested in music, the choirs, and stuff like that.

Nebeker:

So you used to record performances?

Burden:

I'd record them on a wire recorder, then I'd make copies for the performers on disks.

Nebeker:

And did you decide to concentrate on science?

Burden:

My high school was math and science. Although I squeaked through Latin, I really was not good with languages. When it came time for college, that's where I got myself into trouble. They'd given me some aptitude tests, and it showed some good business administration capability —

Nebeker:

Was this an army aptitude test?

Burden:

No, this was in high school. And the guidance teacher went to my dad, who was phys. ed. director at that time, and said that I ought to be pursuing liberal arts. And dad said, "I don't think that's his interest." He said, "He didn't do well in his languages, and I don't think you can convince him." So she and the principal came up with an alternate plan for me. And they got a school that was interested in me because I played baseball to give me a small scholarship.

Nebeker:

So you were that good at baseball.

Burden:

Then I was torn between the two. So I did go to college for one year.

Nebeker:

Where was that?

Burden:

At Lafayette College in eastern Pennsylvania. While I was there, I worked with the local college radio station, and I also played baseball. What I learned out of that year was that my interest in broadcast was really beyond what the college could provide. I left there after a year and went to RCA Institutes in New York. I am a graduate of RCA Institutes.

RCA Institutes

Nebeker:

I see. Tell me a little about RCA Institutes.

Burden:

It would be considered a trade school, but at the time, the course material was very equivalent to what was given in colleges. It was put together in a form that dealt with the electronics of radio. In colleges, the theory was focused primarily on electric power. Now, of course, you have more electronics in college, but not at that time. When you graduated from RCA in those days, there was always a waiting line of people for graduates.

Nebeker:

What year did you enter?

Burden:

I graduated in June of 1949 and went to college. In the following year, 1950, I went to RCA Institutes.

Nebeker:

That was in New York?

Burden:

In New York.

Nebeker:

In Manhattan?

Burden:

Yes, Manhattan. I graduated there in 1952. It isn't like college: we didn't have any summer vacations, or anything. You went straight through.

Nebeker:

But it was the equivalent of a college degree?

Burden:

Yes, it was equivalent. It was twenty-seven months that I went there, which is the equivalent of three years of college. But offer with any degrees. At that time you couldn't graduate without passing your FCC first-class exam; that was required. We don't have those anymore, but at that time, that was a requirement. That was THE test, and at that time you had to know your stuff.

Nebeker:

What was the range of training there at the RCA Institute?

Burden:

Well, we started off with AC and DC circuits, and RCs. We had to understand motors.

Nebeker:

But the intention is that everyone there is going into electronics and radio.

Burden:

That was the intent. I mean, we would get into television. We actually had television equipment that we could work on. We could go through with a scope and see how every stage worked, and understood it in that manner: what different values, resistors or passers or chokes would do to the signal. We could see a scope picture. We had a pretty good idea of what was going on. The thing that I liked about the course is, you had a chance to stop, think and understand everything that you were doing. It wasn't by rote, or anything like that.

Nebeker:

So there was a fair amount of lab work?

Burden:

There was a lot of lab work. Which turned out kind of interesting for me later on in my career. When I got out of school, out of RCA, I went to teach at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. I was 1A.

Teaching Method at Fort Monmouth

Nebeker:

You joined the reserves?

Burden:

Well, I went down to teach as a civilian at Fort Monmouth. They would accept 1As.

Nebeker:

This was a communications school?

Burden:

It was a radar school.

Nebeker:

Radar school.

Burden:

Well, it was a radio, radar school. They put me in the radar school, because I had video experiences. So I went down there to teach, and while I was down there, I decided I would join the reserves and start to put in some of my military duty.

Nebeker:

Did it look like you'd be drafted?

Burden:

Oh, yeah, the Korean War was underway. They were still fighting. This was kind of interesting. I was a few months into teaching, and I happened to pick up a class where the students were Ordnance, not Signal Corps. Evidently the commanding officer at Fort Monmouth had made some sort of arrangement with some other general in ordnance. They wanted to bring these people into Fort Monmouth for this type of training.

Nebeker:

This was radar training?

Burden:

It was radar. They called it electronic fire control, but it was basically radar. These guys had no background in electronics. They were basically automobile mechanics. It was there that I learned that with my background at RCA Institutes, I could relate electrical concepts to physics concepts. I realized that I was working with people who were always able to see everything and touch everything. I mean, that's what an auto mechanic does. And I'm dealing in an invisible world, unless you get across the high voltage, and then it becomes real. So I realized that I would have to show them everything that was going to be done.

Well, I was kind of fortunate, because I was told that these people will learn, they will understand what is going on, and I had some freedom from the course material. So what we did is, we took a basic radio, and we would build a power supply, and we studied all about power supplies. They could put scopes on it, they could put the volt meters on it, they could see how a capacitor charges to keep it up. They could see all these things, and they understood them. Then we did an audio amplifier. Then we did a detector.

Anyway, we followed that concept, the whole way through. We did a lot of lab in with it. After going through all of these stages, when it came time for the final test, this group, with no previous experience, did better than some people that had had a science background. And the question is, why? And I'm saying, well, I had to train them from scratch. I had to make them see and feel the whole thing. Well, then the administration got very interested in what I was doing, and I was asked to oversee a program to offer an alternate program. Then my reserve unit called me back to [laughs — inaudible].

Nebeker:

Had you gotten into some electronics specialty unit?

Burden:

Electronic countermeasures, yeah. The general at Fort Monmouth was a little bit upset about this, because here was the core of a lot of the stuff being done, and the guy is now going to be gone. So we had a conversation. He called me to his office, and I told him what had all happened, and he was a little bit unnerved, because if I had gone through my basic training in the reserves, he could have had me come right back. I guess I was gone a couple of months.

Nebeker:

You hadn't been through basic training?

Burden:

I hadn't been through basic training yet. So I had to go to basic training. I came back, right to the same job, only wearing a uniform and stripes. I was there for another year, and we got all of this program squared away.

Nebeker:

So this was a new program you'd got up and running.

Burden:

This was a new program, yes. So I was there for that, which was pretty good duty. Funny — something my friend said. He said, "You know, the officers are scared of you." I said, "Why? Why are they scared of me?" He said, "Because they think you'll go to the general." I said, "I've got corporal stripes. I'm not a civilian anymore!" I said, "But don't tell them that!" So I had a very good relationship with everybody because I wasn't pushed.

McCarthyism and Security Issues

Burden:

And I was there for a while, a little over a year, and then — Armed Forces Radio. This was the Army-McCarthy hearing time, and we ran —

Nebeker:

1954?

Burden:

Yes, 1954. We ran into some problems there. We had some security problems.

Nebeker:

Fort Monmouth people?

Burden:

Yes, we had some security problems. I was aware of them, and I kept trying to get them resolved, and they couldn't get resolved, not at my level. And of course, when it got uncovered, it was the way things were being handled; then anybody that knew anything about it would have to go somewhere else.

Nebeker:

You were still on active duty in the reserves.

Burden:

I was still on active duty, but the interesting thing about a reserve is, they've got to use you in your specialty or let you go. And I had two specialties. I had the teacher of radar, and I had a broadcast, and those were my two primaries. Being a teacher-radar didn't mean you had the credentials to operate a radar system, because I never got involved with radar systems while I was there. Since the only school was at Fort Monmouth, they looked for p broadcasting, or they had to release me. Armed Forces Radio in New York was looking for an engineer at that time, and I spent the other year with them, which was great duty.

Nebeker:

So it was two years or so of active duty?

Burden:

Yes. I spent ten months back at Fort Monmouth and the other twelve at New York.

Nebeker:

I wonder, since so many people are interested in the McCarthy matters, if you could elaborate a little on the problems that you saw.

Burden:

Well, what really happened was that there were two people at the lab who felt that there were some people there who were filtering information, you know, to others.

Nebeker:

To people outside the country?

Burden:

Yes, outside the country. Russians. Communists.

Nebeker:

Was there was real evidence of this, or just some suspicions?

Burden:

There was suspicion of it. And the people who started this, they removed immediately from the labs. Well, as I told you, my function was putting this program together, and I needed people to help me build labs. Unfortunately, they gave me two people they had pulled out of the Signal Labs, without telling me what the situation was.

Nebeker:

They were pulled because they were suspicious?

Burden:

No, they were the ones who turned the people in. So they pulled them out of that program and offered them to me to build labs. Unfortunately, they never told me who these people were. I didn't know anything about this. What happened, of course, was they were looking for all possible security leaks. Now, we didn't have any leaks in our area, but we didn't have our confidential secret materials under the appropriate lock and key. I had many conversations with a colonel to try to get this resolved. Fortunately, I had a paper trail. It just didn't get done. Of course, these people found what I already knew. I got off the hook because I had at least a paper trail, but then they really wanted to get people out of this whole thing. I do remember the entourage from the McCarthy group coming through.

Nebeker:

Oh, they came through?

Burden:

Oh, yeah. That was just before I left. They listed me as TDY Pentagon. I was at Fort Monmouth, but I had no authority on anything. I would help out and do things. I was just there until the actual orders came through to move me to New York.

Nebeker:

Do you know now if there was any substantial leaking of radar information to the Soviets in that area?

Burden:

I don't think they were ever able to prove it.

Nebeker:

Certainly there was with the atomic program.

Burden:

I just think that it looked like some of that stuff was happening.

Nebeker:

Somebody's procedures were followed?

Burden:

I think that the hearings got pretty political, as you well know, and I think a lot of the original stuff got lost in the politics. I don't think we ever did find out about all these people, but I think some of it was circumstantial and some of it had substance

Nebeker:

Were you yourself uncomfortable in that setting?

Burden:

Well, I was uncomfortable because I knew that I had a security problem. Of course, when they found it, I was uncomfortable, because I hadn't been able to do anything about it. But it was out of my hands.

Nebeker:

I didn't quite understand the nature of that security problem.

Burden:

Well, basically it had to be under certain lock and key.

Nebeker:

Certain materials had to be treated in a certain way —

Burden:

Right, they had to be specialized rooms that you couldn't get in. There should have been bars on the windows and special doors and door locks. And they weren't. We had moved, and the stuff was put into a room that you could get into with a penknife. It was a very simple lock. I said, "This is not acceptable."

Nebeker:

So you tried to correct it.

Burden:

I made an attempt to do it. You have to follow Army procedures. I could have put a hasp and a lock on there, which probably would have made it a lot more secure than it was, but they wouldn't let me do it. I said, "Well, somebody's got to do something." But you know, it's the old bureaucracy. It was only for a couple of months after we had moved that we had this situation, and I was onto it, but all of a sudden these people appeared on the site, and it had not been corrected. We should have resolved the problem of where we were going to put this material before we moved.

Nebeker:

Can you recall how it was more generally there at Fort Monmouth at that time? Were people really upset by all of this or going on with their work pretty much as before?

Burden:

No, they pretty much went on with their work as it was. The hearings and all were after I left. When all this broke loose, finally somebody told me who these people were. I had no idea. My superiors had no idea. I guess personnel didn't want anybody to know, which was kind of dumb, because they never stopped to think about the security. It was just a comedy of errors. Anyway, the Army's procedure was to move people somewhere else.

Reasons for Joining Ft. Monmouth

Nebeker:

I see. And so you were a year or more at Fort Monmouth?

Burden:

Well, yes, if you can count civilian, I was there for almost two years.

Nebeker:

You may know that there's a museum there at Fort Monmouth today.

Burden:

Oh, really?

Nebeker:

And a couple of people there have a real interest in the history of Fort Monmouth electronics and that area.

Burden:

George Van Deusen was commandant of the Signal Corps School at Fort Monmouth during World War II. He retired, and at that time RCA hired a lot of retired admirals, generals, so he became the president of RCA Institutes. I met him in school. I was looking, of course, at the job boards, and he talked to me. We got to know each other reasonably well. Nice man. He said, "The Army doesn't care if you're 1A?." I had taught adult education while I was going to school at RCA Institutes, and with teachers for parents, I had a pretty good background without teaching credentials. On that basis, he said, "This is something you should look into." Teaching is a good profession. It really is. You get to learn your subject material real fast!

Nebeker:

That's the best way.

Burden:

Yes, when you can make somebody else understand it and know it.

Armed Forces Radio and Baseball

Nebeker:

So then you changed to broadcast engineer.

Burden:

Yes. I was broadcast engineer for Armed Forces Radio.

Nebeker:

In New York, you said?

Burden:

In New York. I was stationed in New York. Armed Forces Radio was basically centered in New York and L.A. Of course there were all the overseas locations, but the main groups that were putting out programs were New York and L.A. L.A. had all the Hollywood people.

Nebeker:

Those were the only two places in this country where programs were produced?

Burden:

Yes. We did a lot of news and sports. They used to send me out to the ball games at Ebbets Field, and Yankee Stadium. I used to take my ball glove with me and play catch with them. This was a neat time.

Nebeker:

This was in the 1950s?

Burden:

Yeah, I knew Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, and of course Yogi and Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford.

Nebeker:

Were you still playing baseball yourself at this time?

Burden:

Oh, I wasn't playing. Every once in a while I'd play. I would get out and practice with those guys; I was nowhere near as good as they were, but I could at least enjoy it. They were neat guys. That was a lot of fun in that era, a lot of fun.

Nebeker:

How long did you have that job?

Burden:

Just one year.

Nebeker:

Like 1955 or so?

Burden:

Yes, 1954, or 1955. In fact, the day before I went for my discharge, I did my last job with the Yankees. That was in April 1955.

Nebeker:

You were reporting on the games?

Burden:

No, no, I did the engineering.

Nebeker:

I see — so for a live broadcast.

Tape Delays and Technical Difficulties

Burden:

Some were live and some were recorded at the studio for playback at a different time.

Nebeker:

Oh, you had to delay it?

Burden:

It was just because of the time periods that it was in.

Nebeker:

Oh, I see, not because the Yankees or whoever wouldn't allow you to go live.

Burden:

No. When we broadcast ball games that were out of town. We'd have permission from the league and a feed from their crew. Then we would remove all the commercials — we had permission to do that — and this was when the program delay was first brought in. We had a tape delay of seven seconds. As an example, you hear a ball game now, and they say, "The score at the end of three innings is St. Louis 3, Boston 2." That "2" is the cue word. They'll hear that cue and they'll go right into a commercial. Listen to it today, uses the same cues. When you listened to the output of the delay, and then seven seconds later, you're recording, you'd hear the cue and you'd stop your recording. And you'd listen for the pre delay for the cue to return to the delay, and you’d start the recording again.

What was fun about that, of course, is your ball games get shorter and shorter and shorter and shorter. If you were recording, then they would take each part to the control room and put it on the air. And sometimes, it would only be five minutes before the next reel would be there. If it got much shorter, you'd have to join the thing live, and then of course you'd have to fill! It was a lot of fun!

Nebeker:

So at this time you were using magnetic tape recorders.

Burden:

Yes. We had a loop that was seven seconds long, we'd run it through two machines. Record on one, and play it back on the other. And then we got an Ampex — it went playback head, erase head, record head, and it went all the way around to the playback head again. We had a seven-second delay on that. We got that a little bit later. We originally used two Magnecords that for the delay. It was kind of interesting technology in those days. Of course, today it's all different. With digital technology, it's nothing to put a delay in like that. We did a lot of remotes; I enjoyed doing remotes.

Nebeker:

What were the biggest technical problems you encountered in this work?

Burden:

There were two. I remember we had a windup tape recorder. Travis Tape-pak they called it. We were doing a runner at the old Madison Square Garden. And he couldn't interview for us, but he would be glad to talk with us if we'd run around the track with him while he was warming up. So they went around the track with him. When we got the thing home, it was garbage, absolute garbage, because the flywheel kept changing the pitch. As you run along, you're just jerking that thing. It would slow it up, speed it, slow it. We never realized there'd be that kind of problem. When we got home, we threw it in the wastebasket. Most remotes we did on tape.

Nebeker:

What about live interviews?

Burden:

Sometimes with live stuff you'd have a problem with phone lines. I always liked to get out early. That's why they let me go out to ball games early, that's why I could play ball with the guys, because the line always worked. But if it didn't, then I was stuck with resolving the problems. Every once in a while —

Nebeker:

Were you using ordinary telephone lines?

Burden:

No, they were broadcast-type lines. But the problem was, they didn't use them all the much, and we'd find, under some cases, the phone company would use those loops for something else, and you'd go to plug in — I always tell guys today, you have a dedicated line, have some program material on it, even if it's only tone. That was one of the problems: we didn't do that in those days, and every once in a while you'd find that the loop wasn't there. You'd have to have enough time to fix that. Usually the phone companies were pretty responsive, and you got it up and going in a half hour or so. But that wasn't always true.

Nebeker:

These lines just had a broader spectrum that they carried onto the phone line?

Burden:

Yes, this was a five-kilohertz line at the time. A lot of broadcast lines go up to fifteen kilohertz today. These were five-kilohertz lines, and they would go directly from the ballpark through the phone company and terminate at Armed Forces Radio. They were our lines — we paid for them all the time — but as I say, sometimes the phone company will use them when they knew we weren’t, and then they'll try to put them back, somebody will forget. It's still done today, and this was forty years ago.

But those were the problems we'd run into. I was always very careful when I'd take my remote gear that I'd have everything checked out and make sure everything was going for me before I left. Generally we'd go by car. In 1954 Navy won the Lambert trophy. The Navy sent up a chartered plane to take us down for the ceremonies. Took the Lambert brothers and some reporters. I covered all of radio — mine went to the networks as well as Armed Forces Radio. I took just my sports guy. Just the two of us went from Armed Forces Radio. I remember that, because I was the only guy in an Army uniform at Annapolis.

Nebeker:

Sounds like you got some interesting experience in.

Burden:

Oh, yes. I really enjoyed it. In fact, I was at the Armed Forces Radio here in Los Angeles in December. A friend of mine works over there and suggested I come over just to see what's been changed. I ran across a guy that was at New York the same time I was. He had just retired, in sports. He was in the Navy at the time; I was in the Army. It's always kind of fun to see people like that.

Strengths of Radio as a Medium

Nebeker:

My first memories of radio are of Armed Forces Radio, because my father was in the Air Force; we were living overseas, we didn't have TV. This was in the late 1950s. I just remember those Armed Forces Radio broadcasts and all the Lone Ranger sorts of things.

Burden:

Radio is a great medium. I don't have the feel for television that I do for radio. They call radio the theater of the mind. I can remember sitting by the radio, visualizing all these things. Which in some ways is very good for our minds.

Nebeker:

When you were a kid in the late 1930s or 1940s, did you listen much to the radio?

Burden:

Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. In fact, I've joined the Pacific Pioneer Broadcasters out here. If you're twenty years in the industry you can join. And I've joined, and I've had a chance to meet a lot of neat folks. One of the fellows that I met and really enjoyed was Jim Jordan, better known as Fibber McGee. I was telling him of all the enjoyment that I used to get out of those programs. And one night a fellow by the name of Phil Leslie, who did a lot of shows for Fibber McGee and Molly, was there, and he played a tape that they had done at Christmas time. It was called "The Patient Little Star," which turned out to be the Star of Bethlehem. They wrote it all up. I kind of enjoyed it, and I asked if I could have it. I'm superintendent of our Sunday school here; I thought the kids would be interested. And Fibber said, "Oh, by all means. We play it every year and the family loves it." So I got to know him on a first-name basis. He was really a neat guy. A lot of these people that have been in the field for a long time — Ralph Edwards — all of them are really very gracious people that grew up in those days. It's fun to get a chance to know some of them. It's a great medium.

I don't think we're making as full use of radio as we used to. I think we have tremendous capabilities with the satellite feeds. That was certainly brought out in the Desert Storm situation where we really could listen and know what's going on. There's just wonderful technology out there that we didn't have. It's kind of a shame to see it just all filled with music. There ought to be more to radio than that.

Nebeker:

Well, I don't think we should get into this, but it's interesting that in the last five years talk radio has suddenly become such a big thing. It's a new use, or maybe not entirely new.

Burden:

Oh, yes. It's an opportunity to get people to interact. I think it's wonderful.

Advances in Hi-Fi

Nebeker:

So, that brings us to 1955. Did you leave the Army?

Burden:

I left the Army and I had a job offer, but I got out of the Army around the first of May and the job offer was for August. I wound up driving a school bus for three months and delivering mail. They had a bus route and they had a mail route as well. We lived across the street from the school. One of the bus drivers asked my dad if he wanted a job. He says, "No, but I've got a kid with nothing to do." So I wound up driving a bus. It was kind of fun. Then I went to work for a company by the name of General Precision Laboratory. General Precision had a lot of military work, primarily in Doppler radar.

Nebeker:

Where were they located?

Burden:

Pleasantville, New York. Up in Westchester County, just north of the city. They also had a TV group. When I joined them, they were looking for people to do circuit design. I was involved in some circuit design and some for about two years. Anywhere from power supplies to amplifiers and the like. They'd take and put these things in various stages of a project. It was basically analog while I working there. Most of it was tube technology. While I was there, I encountered a group that started a publication called the Audio League Report. I met one of them just a few weeks ago, and I hadn't seen him for forty years. The Audio League Report was into equipment testing. These guys were engineers at General Precision Laboratory, and they got into hi-fi equipment testing, and putting out their own publication. I didn't have anything to do with the group, other than that I was friends with them.

It was hi-fi heyday in those days, and there were a lot of people who were interested in what was going on in that field. I had an interest in hi-fi and all of that, and got to know a lot of the manufacturers at that time. Bozack, the loudspeaker people — Rudy and I became very close friends for a number of years. I mean, this whole group, the Avery Fishers, the Sol Marantzes; these were all friends of mine, people I knew personally, and I watched their companies grow. Of course, they've all been bought out now. But it was an interesting era, because this was the era of the audiophile. Once it got to be the late 1950s and early 1960s, the mass offshore stuff started to come in. The early 1960s was when the product started to come in from Japan. But loudspeakers are still pretty much made in this country. And you had some English stuff; they had a lot of loudspeaker technology.

Nebeker:

Were there real advances in loudspeaker design at that time?

Burden:

Yes. A lot of work was done on how to make better loudspeakers and FM tuners. I think those were the big advances in that industry at that time. This was the 1950s.

Nebeker:

More than in, say, the amplifiers?

Burden:

Well, we're still talking primarily tube technology. We got involved in transistor stuff in the early 1960s, when the transistor stuff started to come into being. It wasn't that transistors weren't around, but better stuff was being done with tubes. Transistors weren't far enough advanced to do the job. It's a different ball game now.

Nebeker:

I'm just trying to learn what areas were real growth areas at the time.

Burden:

Well, amplifiers went through a big change. Most of them were designed around the Williamson amplifier that came out of England. A lot of work was done with respect to the output transformer and feedback circuitry and the like. A lot of push-pull circuitry came in during that time. It's not that these things weren't known; they just weren't necessarily used. All of that came into being.

A lot of work was done on loudspeaker enclosures. The old base reflex which had been around for a long time sort of took a back seat. The Klipschorn loudspeaker, the infinite baffle, the very small, AR bookshelf-type loudspeakers, they all came into being. That was new technology.

With this group, the Audio League Report guys, we got very much interested in live versus recorded sound. There was Briggs from England who made the Warfdale loudspeakers. He did a live versus recorded performance in Carnegie Hall. We went down to see that. It was kind of impressive. In some cases you could tell the difference and in some cases it was pretty close.

Nebeker:

And how was it recorded?

Burden:

They recorded it in a close-mike technique.

Nebeker:

On magnetic tape?

Burden:

Magnetic tape, yes. Then Avery Fisher did one with the Philadelphia Orchestra. We were invited down to that; in fact, we had dinner with Avery.

Nebeker:

You mean, another one of these comparisons — they did it?

Burden:

Yes, they did it with Fisher equipment. We were invited down to that; we had dinner with Eugene Ormandy. It was a very interesting evening. And we did one with a pipe organ. We did that in Mount Kisco. We had seven or eight amplifiers, and we had some big loudspeakers, and we also used some close-miking techniques.

Nebeker:

Did that work out?

Burden:

<flashmp3>240_-_burden_-_clip_1.mp3</flashmp3>

I was amazed. I could stand in the back of the church — we had little lights tied to the switch. We'd go from mono to stereo, and in some cases you couldn't tell the difference even between mono and stereo. Of course, you got a lot of reflections off the walls too. The organist was great, because his sense of timing was so great that we would play tape, and of course then he would join in live — but that tape would be running the whole time, and we'd switch back to the tape and we'd be right on beat. That was considered a milestone. It was written up in all the magazines. It was interesting. It took a lot of work.

Nebeker:

So was this a popular thing to do at that time, to test your system?

[End tape one, side one]

Burden:

You look back into the 1950s, and of course, those were the times where you had all the big hi-fi shows, where people would come and choose those component-type systems. They'd buy so-and-so's loudspeakers, so-and-so's amplifier, so-and-so's tuners.

Nebeker:

Wasn't that done before very much?

Burden:

Usually if you bought a console radio, you bought it all from RCA, something like that. In some ways we're returning to a lot of that now. People who had interest in the hobby would go to each other's homes and listen to their systems, things like that. It was a hobby.

Nebeker:

You took up this hi-fi hobby?

Burden:

Yes. Oh, I had a lot of fun with it. And of course, one of the interesting things to me is that we had so much better audio off our own systems than you could hear on radio then. There was a real feeling that radio had to come up to snuff. In fact, I think we had better AM radio in the 1930s and 1940s than we do now.

Nebeker:

I see.

Hi-Fi and the Push for FM

Burden:

Bandwidths for AM had been decreasing. FM seemed to be the choice. Most of us who were engaged in listening to hi-fi would listen to FM. That was the push for FM; the people who enjoyed good music went for FM. FM was awfully good in those days.

Nebeker:

How popular was FM in the late fifties, early 1960s?

Burden:

Not popular at all. Penetration was ten, fifteen percent. It was way down.

Nebeker:

Were most radios equipped for both AM and FM?

Burden:

No.

Nebeker:

Because I know you had to buy a special tuner.

Burden:

Usually when you bought a tuner, it would only have FM on it. There were some AM/FMs. You had mostly FM-only tuners. That became very popular, and if you listened to AM on one thing, you'd listen to FM on another. Fischer and Scott and Harmon/Kardon were the big names in tuners, primarily, and Pilot had some stuff. There was an outfit by the name of REL; they made a very fantastic tuner. Radio stations didn't didn’t use heavy audio processing equipment in the FMs. They'd just basically play records, go through a console, and go straight out to the transmitter. You had very good dynamic range, and it really sounded good. Now, this was all mono. I remember listening to organ concerts from Riverside Church. The quality of those broadcasts was just unreal, really beautiful. But still and all, FM really didn’t have the listenership. FM stations were going dark in those days.

Nebeker:

It was the audiophiles who pushed it.

Burden:

That was it, plus stereo played a big part in it.

Nebeker:

Were you involved in any of this in your work there, or was this a hobby?

Burden:

Well, that was a hobby.

National Stereophonic Radio Committee

Burden:

I was still working for GPL in 1958-1959, when I had a fellow come to me by the name of William Halstead. Bill lived in a neighboring town, and found me through the Audio Engineering Society. He is the father of multiplex broadcasting. His work was primarily what's known as SCA, or "subsidiary communications authorizations." These are the background musics, and all sorts of other things today, but it was primarily background music in those days. He was interested in doing something in stereo with subcarriers. The question was how we would get good audio performance using these subcarriers, and what we could and couldn't do. We did a lot of work on that.

Nebeker:

Was this with GPL?

Burden:

No, I was doing this on my own. In fact, I had to go to the president of the company to get released on some of this stuff. The company really wasn't working in that field; this was something I was doing on my own. But I wanted to declare it so that the company couldn't address this at a later date. I wasn't being paid for that, it didn't really relate to my work. I got very interested with Bill, and we were asked to be on this National Stereophonic Radio Committee.

Nebeker:

Who set that up?

Burden:

This was a group with the Electronics Industry Association. NAB was involved in it too, because they felt there was some strong interest in being able to do stereo in radio. At that time, there were also AM stereo proposals.

Nebeker:

This is the late fifties we're talking about?

Burden:

Yes. There were AM and FM approaches, there were even some papers written for the possibility of TV. Anyway, they got this group together once they figured out who should be on it, and had a meeting. And we looked at all of these things. The FCC was also on that panel. Legally, they couldn't be part of the group, but they were there as observers. We said to the FCC, "You know, this is too small of a group to tackle too large a project. Let's do one medium, and then do the others." The FCC at that point really wanted to promote FM, and it was the logical thing to do because stereo and FM was certainly the logical approach. So we did that for two years

Competing Stereo Systems and Bandwidth

Nebeker:

Now this is working up an FM stereo system? How large was this?

Burden:

Well, originally, when we started, there were fourteen proposals. Six were tested.

Nebeker:

Who made these proposals?

Burden:

I don't remember the whole fourteen.

Nebeker:

Were they companies?

Burden:

Yes, they were companies. Out of the six, there was Crosby Labs, of Long Island. There was Multiplex Development, which was in New York, which was the one I was working with. There was Calbest of Los Angeles. There was EMI out of Great Britain. Then there was Zenith and GE. Those were the six systems that were tested. Everybody had a different approach, and they had a reason for their approach. This is one of the first things I learned in going in there. There were compromises everywhere, so the question is, which compromise do you want to take, because essentially you're putting twice the information in the same basic space.

Nebeker:

Was it decided early on that you'd have to live with the current allocations to stations?

Burden:

Yes. We'd have to live within the bandwidth. We've always had that.

Nebeker:

The FCC didn't consider having stereo FM in a certain range where they'd have greater bandwidth?

Burden:

No. No. This was one of the first lessons I learned. It's got to fit in the same place. The EMI system, from Great Britain, was basically a switching type of system. It was not popular at all. I don’t remember much about it.

Nebeker:

Sort of a time multiplexing?

Burden:

It was kind of a strange system. It never had any support in this country. The battle lines were basically drawn between AM subcarriers and FM subcarriers. Once you dropped EMI out, we had three proponents with FM subcarriers and two with AM subcarriers. There's a tradeoff there. With the FM subcarriers, it gets a little more complex.

Nebeker:

Which means the receivers would be more expensive, or —

Burden:

Well, you're dealing with bandwidth. That's the problem. It's got to fit. When you start to add higher frequencies to it, the bandwidth increases; it takes a lot of spectrum. So both Calbest and Halstead restricted their subcarrier in frequency response. We had separation out to eight kilohertz with the Halstead system. The Calbest system had separation out to around three kilohertz. Crosby had full separation across the band. However, to do that, he had to reduce main channel deviation. In other words, the audio dropped down by a factor of two, where Calbest and Halstead reduced the main channel by ten to fifteen percent to add the subcarrier. Dropping the main carrier down by half was considerable. The Crosby system did not provide for additional subcarriers in for background music or whatever. They didn't fit into the Crosby scheme. Crosby was the choice of the hi-fi guys, because it had a full 15kHz separation between left and right channels.

Both the Calbest and Halstead systems used FM subcarriers and were limited to 3kHz and 8kHz in stereo separation respectively because of overall bandwidth requirements of FM subcarriers, but performed better in signal to noise. The GE and Zenith systems utilized AM subcarriers allowing stereo separation to 15kHz but suffered in signal to noise, as they couldn’t apply the limiting advantages of FM. The original GE system did not make provision for an additional FM subcarrier.

Nebeker:

Was that considered important?

Burden:

That was considered unimportant. As Bill and I showed them, it is important. You may be a competitor, but it's important to have this in your scheme.

Nebeker:

Had the companies that you've named put a big effort into developing these systems?

Burden:

Zenith and GE did put a lot in, and Crosby was well written-up in magazines, because it was the hi-fi guy's choice.

Nebeker:

So they had advertised or made public these systems?

Burden:

Well, the magazines were all aware of what was happening. You had people writing articles at that time.

Nebeker:

So were they skirmishing already over the different systems?

Burden:

Well, there was a lot of skirmishing, and of course there's some stuff that I really don't care about. We had big business in there and they were looking out for their interests. What I felt that we should have been doing as a group was looking into taking the best features of the different systems. We did our tests out in Pittsburgh, we used KDKA, and we set up in a motel miles away, in the hills, in Uniontown, and that was the receiving site. We learned a lot about multipath. We learned that multipath was a killer for this type of application. And we realized that that was going to be something that was going to have to be dealt with, and we looked into all those things. We looked at how everything worked under certain signal conditions. We were there just a little over a month making measurements.

Uses of FM Subcarriers

Nebeker:

What was this committee called?

Burden:

National Stereophonic Radio Committee. NSRC. One of our contributions to all of this was economic. FM was pretty poor in those days.

Nebeker:

Financially.

Burden:

Oh yes. I always say, that's when FM meant "forget money." We wanted to utilize subcarriers for different purposes. We wanted to take that stereo subcarrier, and if you weren't broadcasting stereo at that time, use it for something else. The receiver was going to have to be able to tell whether the broadcast was in stereo or not. We had a plan in our system for a pilot signal. We were going to use a low-frequency type signal to turn the receiver into stereo, and give some sort of indication that there was a stereo program. That's where the stereo light comes from. That was our technology then.

Nebeker:

That's the pilot signal that's sent whenever the stereo is being sent.

Burden:

Yes. The nineteen-kilohertz pilot to turns it on and off. Our concept was the same. We didn't have nineteen-kilohertz in our plan, we used something else. But we felt that it was very important to have someone realize that there was stereo there. Now, of course, you see that in everything. We have the patent. We never derived any income from it, but it has been well used.

Nebeker:

Now, the idea with the subcarriers for the FM stations was to earn some extra money?

Burden:

To earn extra money. We needed it. It kept a lot of them on.

Nebeker:

What were they principally used for?

Burden:

At that time, they were principally background music for stores, elevators.

Nebeker:

Who was marketing? Muzak?

Burden:

Muzak was a big company. There were other companies, but they were all like Muzak. There were also specialized services. Now we have reading for the blind, we have Doctor's Network, and fax on them. There are all sorts of applications that you can use on those carriers now. At one time, Southern California Edison was going to use them for load shedding. In summertime with air conditioning the need for electricity increases — a signal to shed some of the load could be negotiated with the power company for a better rate, you could work a deal with it. Remember all that?

Nebeker:

We have that on our air conditioner now. And that was coming from an FM subchannel that could control power demand?

Burden:

You shed power by the use of FM subchannels. There were many, many uses for subcarriers. Now we get into the digital age, and many other capabilities. What's new on the horizon is what we call RBDS, Radio Broadcast Data Service. You can now have a readout on your FM radio that can display station to call letters, the frequency, or emergency messages or whatever you want to put on it. It's a standard. I worked on that. I've been pushing for something to be done for AM in that regard as well.

NSRC Tests and Recommendations

Nebeker:

So, to return to that account of that committee, you made these tests?

Burden:

We made all the tests and provided all the data. In this case, the FCC made the decision based on the data. But they also knew why everybody did what they did. It was up to them. In our case, the Halstead system had the best signal-to-noise, but the separation was only good to eight kilohertz. With Crosby, the main channel was reduced by too much. With the GE and Zenith, what was there was the tradeoff from signal to noise, but they felt that people would prefer separation all the way across the band.

Nebeker:

How did you phrase or form your recommendation for all these different systems?

Burden:

Well, actually, we attended some of the hi-fi trade shows. We used two great big concert speakers, and actually run programs through the system with our filters in there and ask, "Do you hear the differences?" We also used a different audio matrix, because we wanted to be compatible with AM/FM stereo. So our matrix was a little bit different. We advocate a one-to-one relationship; as in left-plus-right as a monophonic signal, as the channel polarity can get reversed. You've heard it on the radio, it sounds like the singer's off in the bathroom somewhere and you've got this full orchestra. That's what happens when you get channels out of polarity. I was very concerned about that. There's a lot of tapes and stuff out with the channels out of polarity. They did it for enhancement, and it was fine in stereo, but when you play it back in mono, it sounds odd. So we were very concerned about that kind of thing happening. The FCC wasn't as concerned about that issue, although when the problem did appear, they had a better understanding of what the problem was. There was a lot more of it than the group had recognized.

Nebeker:

I see. When did this committee make its recommendations?

Burden:

The committee started to meet in 1959, the testing was done July-August 1960, and the stereo decision was made in April 1961.

Nebeker:

I see. And, as far as you know, how did your committee feel about the FCC decision?

Burden:

Oh, they were fine.

Nebeker:

I mean, did they take everything into account?

Burden:

Yeah. We'd made provisions that applied no matter which system you used, with the exception of the Crosby. SCAs were in place. We felt that was very important. Everyone but Crosby felt that way. I guess the Commission did, too.

Then there was the question of, "Did you want separation versus signal-to-noise?" That was what the issue was. Although Bell Labs backed the position Bill Halstead and I had taken, it was felt that somewhere in the future, that might produce a problem. The theory wouldn't let you out of that. In the case of the AM subcarriers, if you have a better receiver with better sensitivity, the noise problem starts to diminish. I guess that was the reason why that was adopted as the standard. As the receivers got more sensitive, the problems diminished. Also, we're using a lot more audio processing than we did in those days, and of course that's a big factor in improving signal-to-noise. So, technology was able to improve that, where we were up against theory with the position that Bill and I had taken. It was interesting to see people come together and work on a common problem.

Nebeker:

Did you find that the people on this committee were able to be impartial?

Burden:

Some were, some weren't. It depended on the company and the personality. In most cases, people were pretty congenial. But there were some companies that were out to push, and that does happen. I sat on a similar committee doing the TV-stereo. Everybody worked together for a common goal. The committee, through voting, made their recommendations, and the Commission adopted it. That was different. The Commission actually made the decision on FM stereo. With AM they started with a committee.

AM Stereo

Nebeker:

When was this?

Burden:

Let's see, that was in the 1970s. In the 1970s they did the AM. I don't know why they didn't do the AM stereo immediately after we did the FM, but they didn't. What happened was that one proponent didn't submit his data to the group. He submitted it directly to the FCC, because he didn't want to become involved with the group. That presented a problem, for openers. Then, the FCC looked through all the data, really sat on it for quite awhile. Then, they made a decision, just prior to a broadcasters' show. Now, you look back to 1961, when they made the FM stereo, they made their announcement at the NAB show, because this was broadcaster-related. Our Commissioner at the time made a decision to make a decision in time for NAB. I guess he didn't give enough for his workers to really go through with it. They developed a matrix. What kind of importance should you put on each facet? Everybody takes a different view of how to put this thing together, so these people put together a matrix of what they thought was important.

As a result, the FCC endorsed the Magnavox system. I'd listened to the Magnavox system; it was fine. I mean, I may have had preferences, but it was certainly acceptable. At that time, there were many people in Motorola and [other] camps who said, "Why Magnavox?" Then our FCC chairman said, "Well, maybe we ought to go back and look at this thing again." Wrong choice of words, because from then on it's subject to lawsuits. They're still going through it. They tried to do it with opening it up to the marketplace, which was fine, but now you're dealing with salesmanship, not technology, and as a result AM has not been widely accepted. And yet, I've listened to some very good AM stereo.

Nebeker:

What do you mean, "opening it up to the marketplace?"

Burden:

Well, very much like how VHS and Beta went into the marketplace.

Nebeker:

So, they could be different?

Burden:

Yes, they could be different. There was a switch. You could listen to one or the other; I have a radio that does it. You fight it out in the marketplace. VHS finally won, although Beta is considered maybe a little bit better. VHS was the one that made it. This is the same case with AM, except that there hasn't been the interest in AM to resolve it. They'd have been better off with a standard.

Nebeker:

So AM stereo would have caught on or have been a better success if the FCC had set a standard.

Burden:

It probably would have been better, because now every receiver manufacturer has got to deal with two licenses rather than one. It wasn't well thought-out.

Implementing FM Stereo

Nebeker:

To return to your career: was it in the late 1950s that you started work on this?

Burden:

Yes. I left General Precision Laboratory in 1960, just about the time we were doing the tests, because there was going to be a lot of interest in whatever system was going to be chosen. These things were all going to have to be installed, and people were going to have to understand them. People were going to have to rewire studios. You just couldn't run two channels; they had to relate to each other. A lot of broadcasters didn't understand this. The phone company certainly didn't understand it at that time. I had this interest, interest well over financial gain, in working with the broadcast stations to develop good stereo signals.

The problems were in the studios, in the phone lines between them, the transmitters, the antennas not being tuned — just the whole gamut of those things. There was a real period in there, from about 1961 to about 1965-1966 when a lot of this issues needed to get straightened out before FM stereo became commonplace.

Nebeker:

How were you employed in that period?

Burden:

I just worked as an independent engineer. I'm still doing other things to this day as an independent engineer.

Nebeker:

So you'd work for a while with one broadcaster?

Burden:

I worked with many broadcasters. I did one of the early ones, the fourth or fifth station on the air, which had all sorts of problems. I even spent some time with RCA showing them the problems. The idea in those days was to go to transistor, and that was a mistake in this particular case because of temperature problems. When they finally went to a tube version, that finally got it going.

Nebeker:

Do you mean the heat generated by the transistors or components?

Burden:

Varying temperatures in the transmitter plant would change the parameters of older transistors.

Nebeker:

Oh, I see. So the transistors were more sensitive to temperature.

Burden:

Very sensitive to heat. I'd get everything adjusted, and then the heat would change, and I'd have everything out of adjustment. That was a real problem.

Nebeker:

And that didn't happen with tubes?

Burden:

It didn't happen with tubes, because the temperature was pretty constant. Semiconductors weren't that far along, or at least the ones they were using weren't. It was really tube technology. See, it was around 1961, when we put the first one in. This was only a few months after. A lot of this technology was done in the labs. The idea that temperatures vary in the transmitter plant was not well thought out. So they went back to tube technology for their second version, and then they finally put out the transistor. They finally replaced most of this stuff with tube versions, as this resolved the drift problem. Once you get filaments and heat it, the temperature's pretty stabilized. With some of the early transistors, room temperature made a big difference. These were all lessons that we learned on-site.

Nebeker:

People must have felt that the future belonged to transistors, and they moved too early to transistors.

Burden:

That's right. They moved too early and the technology wasn't quite there.

Nebeker:

Can you give me a typical scenario of what you do for a broadcaster interested in stereo FM?

Burden:

Well, at that time, what we'd do is, come in and look through their control room, and work with them on the audio. People don't realize that a db of difference between the two channels will take you down to just minimum requirements as far as separation. It'll take you down to thirty db just like that. Also, just a few degrees in phase relationship will do a similar thing for separation. In many cases, in the wiring, you have capacitance in the cable. If you had one cable run that was much longer than the other, then the phase relationship between the two channels was off. Even though the amplitude wasn't affected, the phase relationship would be, so that you couldn't separate the two channels on the other end. Broadcasters weren't used to that. They were not used to relationships between two channels.

Nebeker:

So the stereo system just made greater demands on audio.

Burden:

It made greater demands, and the average station engineer was not versed in this. The average station engineer in those days was primarily a transmitter man who pretty much understood audio and matching and doing all the proper things and getting a good signal-to-noise ratio. There were good, proper procedures for those days, but they didn't have the understanding that the left and right channels had a relationship to each other and that they could null a monophonic signal.

Nebeker:

There wasn't the separation of labor between the studio engineer and the transmitter engineer in a lot of stations?

Burden:

There were in some of the larger stations, but not in the smaller stations. And again, the FM boys didn't make the money that the AM guys did in those days. The smaller operations were the ones we were dealing with. This was a training period. Now they understand. But people didn't understand the relationships between the two channels. They thought you'd just run left and right. Well, you can't, as we learned and were able to show. In many cases, I can still hear stuff that isn't as good as it should be. It was an era of learning, for everybody. Of course when you start to put this extra circuitry into transmitters, we found that some of the transmitters had trouble with separation. So we had to get into working on the transmitters, on how to get the phase and the amplitude relationships in the transmitters to be consistent.

Nebeker:

Was this a matter of adjustment of the transmitter, of the design?

Burden:

Some of them were adjustments, but for some we actually had to work on the design.

Nebeker:

The stations were buying commercially produced transmitters, is that right?

Burden:

Yes.

Nebeker:

But they just weren't up to the new signals?

Burden:

Older transmitters were not designed to do that. It was the phase and amplitude differences between the two channels within the transmitter that presented the problem. So that becomes an issue. These were things which the average engineers in that period wasn't aware of, so they didn't get the results. Antennas were another problem, a major problem with multipath. If they weren't tuned right, they would send signal back down into the transmitter, and that would wind up phase-displaced and get into the carriers. You would hear crosstalk, and buzz, and funny things.

Nebeker:

What was required there, new types of antennas?

Burden:

Wider-band antennas, making sure that they were really a good match into the transmission line. Again, this was something that was not understood. A lot of the old antenna designs were reasonably narrow-band, and had problems. Some people lucked out: the antenna was well tuned, matched everything well, and you it'd work. For some people, the antenna was not well tuned. They'd say, "Well, the manufacturer tuned it." Well, we learned that that's not good enough.

Career as Independent Engineer

Nebeker:

How was it for you? I mean, that must have been a momentous step, to leave a well-paying job with a laboratory, and then go off on your own.

Burden:

Yes, it was. I debated that for quite awhile. It was another fellow working for the FCC who said, "You've got an opportunity here. You're at least known in these circles as contributing to these types of things, and you ought to take advantage of working on this and being known by the Commission for your level of engineering expertise." It has paid off. I might have stuck to the same company, but that company no longer exists. It had about two thousand employees and it no longer exists!

Nebeker:

You've been an independent since when?

Burden:

I've been independent since 1960. I guess there are financial rewards in some cases, satisfaction in others. I've had a chance to be with people on the leading edge of things. I've worked with people who are tops in their field. The people who are asked to be on the committees are top people. When I need questions answered, I know I can pick up the phone and call a lot of people. I've learned some things which I might not have at this research job that I had years ago. I might still be in that little cubicle doing certain little things. You do get a wider perspective.

Nebeker:

There are obvious advantages, but then there are also ups and downs. There might be times when it's very difficult.

Burden:

The financial advantage was not there. Oh, yes. Any independent guy has that problem. Over the years I've been able to put a roof over my head and food on the table. I've enjoyed what I'm doing, and I suppose there's a lot to be said for that. I don't have to fight myself to go to work in the morning.

Nebeker:

Well, being your own boss is a great thing.

Burden:

Yes, it is. And it's been a pleasure over the years to serve on these committees and to have a chance to put my two cents in. In many cases I can look back on proposals and things that are done where my two cents is in there. I've made my contribution, and I'm pleased that I was able to do that.

Television Sound

Nebeker:

Can we run through the more important commissions that you've been involved in?

Burden:

Well, I was involved in the FM stereo. I worked on the TV stereo and I worked on the Ad Hoc Committee for the Study of Television Sound.

Nebeker:

Do you remember, roughly, when that was?

Burden:

Yes, that was 1973. I was the person from AES assigned to that committee: I was the one that they picked to look at the views of that society. We started to look into all the ways and all the areas where sound is hurt by going through the audio chain of a TV signal. We looked at everything from microphones, to cabling, to where it's hung, to the acoustical environment, through consoles, through the transmission system, through the cable television system, and out through the old three-inch loudspeaker. One of the interesting things that I was able to learn over time was that we kept coming back to this three-inch loudspeaker. Why make it any better?

Also, at the time we worked on that, television was pretty much relegated to about five kilohertz frequency response, when it was off network, because it went through regular audio telephone lines. Our group was involved with putting subcarriers on the video channel so that high-quality audio went along with the picture. That allowed 3 channels of 15kHz audio routed with the picture. And that made a big difference in television.

Nebeker:

When did that happen?

Burden:

That happened about 1975, I think. We were very interested in that technology.

Nebeker:

So you made this analysis of the whole path of the sound —

Burden:

The whole path, as to where all the problems were.

Nebeker:

And what were the major problems?

Burden:

Well, that one of them was the network area. Also, there had to be an improvement all the way through the chain. The original group, as we started, was only looking at the thing monophonically. Tom Keller and myself objected, "You can't do that. There's already stereo FM out there. There have already been proposals for TV stereo. We cannot and should not look at anything that would preclude it." I didn't say that out of this group we should come up with a stereo standard, but whatever we were doing, we shouldn't do it in a manner that would preclude it. That got very important when we got to fifteen kilohertz audio along with a composite picture, because we had to have room for at least two carriers there. So that was an important decision, I felt, doing that. And of course, for the rest of the thing, when you clean up the mono, in many ways you've cleaned up a lot of the stereo.

One of the things I was very interested in doing was to set up a control room in which you would listen to programs. In recording we run these levels very, very high, where in TV there is no need to run those levels that high. You want to run it louder than you'd run it in the home, so that you can hear anything that might be in there, but you didn't want to run it into the point where you had hearing damage. This was becoming a concern at that time. So they'd ask, "What do you think?" And I'd say, since 90 db is our threshold for possible hearing problems, let's come back at least a couple of times for that and make it 84 or something like that. There were some objections to that, because they felt that there ought to be a lot more research on what the numbers should be. There was research: CBS came up with 83, and the motion picture folks came up with 85. I guess I was close enough. But at least there is a standardized level for listening now, as a result of that.

[end tape one, side two]

Burden:

In FM, we have a channel that's two hundred kilohertz wide, and we deviate seventy-five kilohertz on either side of that, for one hundred fifty in total deviation. When we get into television, there was the same bandwidth, two hundred kilohertz, yet for many, many years, for as far back as we can look, they've only deviated twenty-five kilohertz of that. That leaves a lot of guard band. The deviation was limited to +/-25kHz. It was in the days where we had a separate IF for sound and video. In the early days of TV, the oscillators in the TV sets used to drift. In reading textbooks, I found that the FCC limited the deviation to +/-25kHz so that the drift wouldn't be a problem. And that was sufficient even then. We've since dropped aural carrier power levels back further and further as the state of the art has increased. We never went back to deviating higher.

My concern was that when we went into FM stereo, we added subcarriers. We had to include them in the total deviation. But since TV had the same bandwidth, why couldn't we increase the level of the subcarriers without having to subtract anything from what we call "main carrier" now? So we did some tests, and found that you could raise the total deviation to seventy-five kilohertz without affecting the picture. On some of the poorer sets it was somewhat noticeable, but with the average set, there was no change. This allowed us to add the subcarriers without taking away from the main carrier. That improved signal-to-noise, which was very important in television. So I felt that those things made it happen.

Television uses a similar technique to that used for FM stereo, except that the pilot signal is now related to the TV picture horizontal, frame rate. In addition to that, we've put in some noise-reduction schemes that are not in FM. It was a pretty good standard. There are some things that I think that could be done to improve it, generally, but the television stereo is pretty damned good. So, it's nice to have been a part of things like that.

National Radio Systems Committee

Burden:

And the last group I've been involved with is what is now known as the National Radio Systems Committee. They looked at a number of things, one of which was improvement of AM. The interesting thing about improving AM is that we do things that basically reduce its performance a little bit. Generally AM stations were allowed to modulate with a frequency response out to fifteen kilohertz. But receiver manufacturers narrowed the bandwidth of the receivers to reduce that interference from adjacent stations. So the idea was to narrow the transmitted band and open the bandwidth of the receiver, so that they were more complementary. It was the work of that committee, to look into those things.

Nebeker:

When did that committee meet?

Burden:

That started in 1980, and most of the work was done towards the end. It pretty much ended by 1990.

Nebeker:

I don't know if it's special because of my location now, where I live, halfway between New York and Philadelphia, but so much of the AM spectrum is messy. It's just hard to get good, clear stations.

Burden:

Oh, yeah. Well, we've learned some things. It's based on alternate channels. In most cases, if you can solve the second adjacent channel problem, you've got it. It's the old 80/20 rule, you solve eighty percent of the problems.

Still, we did some research, because we were looking to try to do something for radio broadcast status systems on AM. They were looking at receivers that were ten kilohertz wide. When you open the bandwidth up to ten kilohertz, if there's a strong first adjacent channel, you will hear a 10kHz carrier beat. This was learned many, many years ago when whistle filters were part of the better AM receivers. The Amax receiver, called the standard receiver, is in the work of the National Radio Systems Committee (NRSC) which exhibits frequency response out to 7 ½ or 8 kHz. going out to seven and a half, eight kilohertz for an audible signal. And it's pretty darn good audio, it really is. It's missing an octave off the top, that's what it effectively does. By doing that, you get an acceptable signal without this ten-kilohertz beat.

When we went to RBDS, trying to come up with a concept that we could use there, we got into a situation where we could put two high frequency tones out there, for that, up around nine kilohertz, and then on a standard eight kilohertz receiver, it couldn't be heard. Some broadcasters wanted to have a receiver go out to ten. Well, then you can hear it. Even it's way down in the mud, it's there. But at night, all the other adjacent channels are there as well. So I'm not too sure it matters. The fact is that the number looks better, and I'm not sure that you get a clear, audible difference. It's been the stumbling factor to being able to put the Radio Broadcast Data Service on AM. That is too bad, because we're talking about a service now that can tell you if you are tuned to a sports station, news station, religious station, whatever. But it is only available on FM. And to me, if you're searching on the AM band, that doesn't make any sense.

There was also a proposal to store program format in the receiver. Well, that's all well and good, but it did not address a variable format. KABC out here, in Los Angeles does talk, as well as broadcast the Dodger games. So your display will go to either talk or Dodgers You can't change it because it is a static displays stored in the radio." I don't think that's a good idea. I really don't: it serves some purpose, but not others. There is a placeholder in the document so you could add AM RBDS in there.

Nebeker:

I am not informed on these matters at all. I take it that FM has such a standard in place?

Burden:

Yes. There's been a standard in place since 1992. I was part of that group. It's been fun doing all these things. It can be. I think it's considered to be one of the approaches for redoing the Emergency Broadcast Service. Although our FCC chairman says you'll turn on the radio and it'll tell you that there's a problem, what it won't tell you is to turn on the radio. You can resolve these problems, if the radio's on. Yes, we can do it. We can un-mute the radio, but if the radio's off, nothing's going to happen.

Nebeker:

We could all have remotely controlled radios?

Burden:

You can resolve it, but you basically have to have a situation where the radio's on to be able to accomplish that. Any time the flag comes up and says it's an emergency message, it can un-mute, but it has to be on. We all got a kick out of the chairman's remarks at our meeting in January, where he was up here in Las Vegas at the Consumer Electronics show, making these great prophecies with nothing to back him up.

Reader's Digest

Nebeker:

Now, you were in the New York area in the late 1950s and 1960s, and now you're in California. When did that happen?

Burden:

It happened in 1972. I did all sorts of things in those days.

Nebeker:

You were probably traveling a bit.

Burden: