Oral-History:Joel Snyder: Difference between revisions

m (Text replace - "IEEE History Center Oral History Program, 39 Union Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901-8538 USA" to "IEEE History Center Oral History Program, IEEE History Center at Stevens Institute of Technology, Castle Point on Hudson, Hoboken, NJ 07030 US) |

m (Text replace - "and Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey" to "") |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

<p>JOEL SNYDER: An Interview Conducted by Mike Geselowitz, IEEE History Center, June 10, 2009 </p> | <p>JOEL SNYDER: An Interview Conducted by Mike Geselowitz, IEEE History Center, June 10, 2009 </p> | ||

<p>Interview # 508 for the IEEE History Center, The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc. | <p>Interview # 508 for the IEEE History Center, The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc. </p> | ||

== Copyright Statement == | == Copyright Statement == | ||

Revision as of 16:19, 30 June 2014

About Joel Snyder

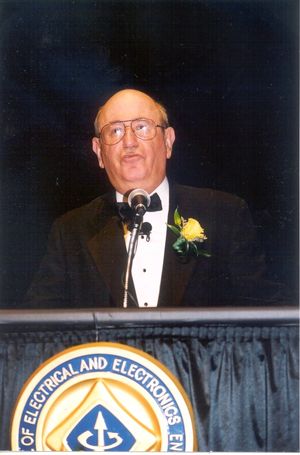

IEEE President in 2001, Joel Snyder received BEE and MSEE degrees from the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn. He has worked for Harman Kardon, Airborne Instruments Laboratory, and IBM in removable media disk memories, voice-over-data modems, speech compression techniques, nonlinear sampling techniques, redundant and parallel computer systems and holds patents on video piracy prevention techniques. He has also taught at Polytechnic University, Brooklyn, the New York Institute of Technology, and Long Island University. He is currently a consulting engineer and principal of Snyder Associates in Plainview, New York.

About the Interview

JOEL SNYDER: An Interview Conducted by Mike Geselowitz, IEEE History Center, June 10, 2009

Interview # 508 for the IEEE History Center, The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.

Copyright Statement

This manuscript is being made available for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the IEEE History Center. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of IEEE History Center.

Request for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the IEEE History Center Oral History Program, IEEE History Center at Stevens Institute of Technology, Castle Point on Hudson, Hoboken, NJ 07030 USA. It should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

Joel Snyder, an oral history conducted in 2009 by Mike Geselowitz, IEEE History Center, New Brunswick, NJ, USA.

Interview

INTERVIEW: Joel Snyder

INTERVIEWER: Mike Geselowitz

DATE: 10 June 2009

PLACE: Plainview, New York

Early Life and Education

Geselowitz:

This is Michael Geselowitz from the IEEE History Center, and I’m here in Plainview, New York with past president of IEEE, Joel Snyder, conducting an oral history interview. So, Joel if you would, tell me how you got started as an engineer.

Snyder:

Well, I got started not as an electrical engineer. My first love was chemistry, and when I graduated high school, I went to Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn. I was studying chemical engineering.

Geselowitz:

Where did you go to high school?

Snyder:

James Madison High School in Brooklyn.

Geselowitz:

Yes.

Snyder:

And then I enrolled in college. I went to Brooklyn Poly—in those days it was Brooklyn Poly, now it’s the Polytechnic Institute of New York University—and I started studying chemical engineering. I took many chemical courses of various types and on various subjects, and in the second half of my sophomore year one of the courses was organic chemistry laboratory. I took one walk into the laboratory in the opening day, took one smell of what was going on, and I decided this is not for me. That’s when I promptly left the chemical engineering department. I dropped out of that particular course, and I switched to electrical engineering, which was my second love. I went to summer school to make up missing courses, and I’m the only graduating EE, at least in that era, who had so many credits in chemistry that I could have had a minor in most universities in chemistry, if not another major. And that happened to serve me pretty well in my career because, in a couple of jobs I worked on, the knowledge of chemistry made a big impact and made things a lot easier for me. As to when I started in IEEE, of course in my junior year I was a full-fledged electrical engineering student, and I thought that I should join a group with other EE students. So, I joined the IRE and the AIEE chapters at my university, and I have been a member from then on out. I’ve always been a member since my sophomore year, or actually my junior year in college.

Geselowitz:

What year was that?

Snyder:

It was 1954 when I first started as a member of AIEE and IRE. I started college in 1952. After, my bachelor’s degree I continued part-time as a master’s student and went to work in industry and stayed in the IEEE. I didn’t become active until the middle 1970s. In middle 1960s I went on my own as a consultant. I started to do a little bit of part-time teaching and consulting, and I said, gee, I need the networking capability of the IEEE. So, I became active in my local section.

Geselowitz:

Where were you living at this time?

Snyder:

By that time I was living in Plainview, Long Island and I became active in the Long Island Section. There was a chapter, the Computer Society and I started out as secretary and then became chairman of the chapter and then went on to become chair of the Section—serving in all the posts on the Section Executive Committee and becoming chair of the Section two different terms.

Geselowitz:

What was the first year you were chair of the Section?

Snyder:

1972 I think it was, 1972 or 1973 when I was chair of the section for the first time.

Geselowitz:

As a section chair, did that bring you into touch with IEEE as an international organization, or was the central headquarters still some remote thing?

Snyder:

Well, no—as a section chair, your biggest concern is the local activities. However, you also participate in the regional activities. You—all the section chairs—go to the regional committee meetings. And the regional director at that time, whom I became very friendly with, was Hal Goldberg who went on to become VP of RAB and then went on to become the first chair of a major committee called USAC, United States Activities Committee, which then became USAB and now is IEEE-USA. And first of all he asked me to chair some committees in the region. Then he asked me to chair a committee on USAC, and that started me going on the national/international level. And from then on it was downhill, if you will.

Geselowitz:

So, what were some of the activities that the regional committee?

Snyder:

Well, on regional committee I was chair of the by-laws committee. I wrote the by-laws for the region. I was in charge of a couple of the regional events. That was pretty much it. I served on the regional committee only two years, so I didn’t have a chance to do very much.

USAC

Geselowitz:

Then, and then through that you got involved in USAB?

Snyder:

USAC in those days.

Geselowitz:

USAC, okay. This is the late seventies?

Snyder:

Late seventies—I’m trying to recall who was chair of USAC when I first became involved. I think that may have—the second chair was Leo Young. I started with USAC when Hal Goldberg was chair, and he had me chair the Ethics Committee, and we went on the next year to prepare a Code of Ethics for the IEEE, which it turned out became the second Code of Ethics. There was a Code of Ethics established in 1907 or 1917, I don’t recall the date now, which no one knew about. It had fallen into the cracks somewhere. We dug it out. We found it after the Board of Directors approved a brand new Code of Ethics. We found the old one.

Geselowitz:

It’s interesting to compare the two.

Snyder:

There were some similarities and some major differences. I also chaired the committee when USAC became USAB. If you recall, there was an ethics case involving some engineers in California, the Bart case, where some engineers claimed that the fail-safe system had failure modes. And they were fired, and sued and we ended up submitting a brief to the courts—IEEE got approval at the board, and I chaired the committee which did it. They said we couldn’t take a side, but what we could do is take a side on ethics. And we submitted a brief outlining what are the normal ethical constraints for engineers. The brief was accepted by the court, and the engineers ended up winning the case, which was nice. Then I went on to other things in USAB, and from there on out, a thousand different posts.

Geselowitz:

Now, eventually you were president of USAB?

Snyder:

Right, and it was USAB. It was being called IEEE-USA by most folks, but it was still officially USAB. It wasn’t until while I was VP of Professional Activities and chair of USAB that we became known officially as IEEE-USA—period. In USAB I chaired a lot of different committees. I was active in licensure and registration. I lobbied on the hill for pension reform. I lobbied on the hill for a number of things. In 1976, I guess it was, Jim Mulligan was chair of USAB, and I was his controller, treasurer for USAB. The next year John Guarrera, another IEEE past president was chair of USAB, and I became his vice chair. And then I went on to stay as a member at large in USAB after that, and then I went off of it and came back again as a regional director.

Geselowitz:

So, what was your first stint on the IEEE Board of Directors?

Snyder:

My first official stint was as Region 1 Director. Before that, I was chair of the Committee on the Bart Case, and that goes back into 1975.

Geselowitz:

So the Bart Committee was an ad hoc committee of the Board of Directors?

Snyder:

Yes, of the board.

Geselowitz:

Now, would you like to say something now, or maybe it will come back later when we get to you moving up through the ranks of the IEEE Board of Directors, this tension of IEEE wanting to be perceived as a global organization versus needing to serve the needs of American engineers who unlike foreign engineers did not have another voice.

Snyder:

The phraseology you use is a little bit of an anathema. The reason is there was never really a conflict of who does what. It was more a conflict of, gee, you’ve got a mandatory assessment for USA members, and that’s not fair. The societies, two or three of them particularly, did not like that. As far as they were concerned, they were doing enough for professional activities. They did not do any lobbying or anything else, but they were doing enough, and some of them didn’t even understand what USAB did. As a matter of fact, at one time we went before the Board of Directors. I think this was 1977. We went before the Board of Directors with a proposal to give—put in a voluntary contribution on USAB members so that we could form a PAC, a Political Action Committee. The charter of the PAC would be to make equal contributions to Democrats and Republicans on both sides of the aisle in both houses, Senate and Congress. And therefore we could have entry into their offices to talk about things, and one of our directors, bless his heart, got up and said, well why should we have to make contributions to get their ear? After all, we’re the world’s leading experts on this stuff—not understanding at all how the political scene works. If you’re not a constituent, you don’t get to see the person. You might see their assistants. If you’re a constituent, you might get to see the Congressman or the Senator. If you’re a contributor, you get to see them for 10, or 15, or 20 minutes, and that’s the hierarchy. This particular director was so naïve, and he was a PhD in a couple of different subjects and way up there in the academic ranks, but had no concept of the real world. Unfortunately, that did not pass, so we did not have that, but the idea that a couple of our societies felt that we shouldn’t have to go after things to talk about, they should be coming to us. And that’s what really it was—it was not a battle of any sort. It was really that was part of it, and the fact of American engineers were paying a required assessment irked them. They felt, well, societies are optional, shouldn’t this be optional. The answer is the society depends upon your technical specialty. This covers everything, so in a sense, this was the argument we used.

Geselowitz:

Right, and it was automatic, sort of the opposite of a dues reduction in a developing country. It was everyone who has a certain zip code was just charged the same.

Snyder:

That’s right. Period. All Americans get the same services out of IEEE-USA. They always did. Let’s face it, there are people who don’t want IEEE lobbying, who don’t want IEEE to give testimony on—for example, position papers on air traffic control, positions on communications allocation and bandwidth, that didn’t want the IEEE to give testimony on those things. Why? I don’t know. Those are technical topics, and the IEEE should give information on that. And the IEEE-USA was the only body that did it. Yet, people objected. Hey, you’re not a technical organization. We should do it. Well, if you should do it, then do it. That was the argument that was made. So, up until this year at least we’ve been very successful in holding people who were naysayers at bay and saying, look, we do a lot of good and the number of times Congress has praised our Congressional fellows or administrative fellows, the number of times we’ve been invited to White House affairs and shaken hands with presidents, proves that we are making an impact. Some people don’t like that. That’s their problem, but to bar it from other people is not appropriate.

Geselowitz:

That’s a good answer. So, you were I guess you said in 1992 you were the region director.

Snyder:

1992 and 1993 I was the Region 1 Director. I served on the board. I served on USAB in those days also, and I accomplished those tasks assigned to me by the Board, and whatever Luis Gandia as VP of RAB in those days assigned to me. After my term of office was over, I was a candidate for VP of RAB, but I was beaten out by Vijay Bhargava, who won the election that year. And the following year I became Vice President for Professional Activities so I took over as chair of USAB. I was in that job for two years in a row.

Geselowitz:

Was that also a board position in those days?

Snyder:

It was always a board position. The VP of Professional Activities was a member of the Board and a member of the Executive Committee.

IEEE-USA Reorganization

Geselowitz:

And do you remember what some of the main issues were that you tackled in those two years?

Snyder:

Well, as chairman of IEEE-USA, the biggest issue was reorganization in 1996 when IEEE-USA moved from becoming a Board, a sub-committee of the Board or a Board of the Board and became a full-fledged Board on its own. Instead of being a VP for Professional Activities, we wrote our by-laws and we made it into a President of IEEE-USA directly elected by the IEEE USA members. The old way, the VP was elected by the IEEE Assembly, which included the ten regional directors, the ten divisional directors, which included the outside USA people, so it was an oddball way to elect a president of USA activities. So, by going to a directly elected president, it changed things considerably, and that’s the way we’ve been ever since. That was done in 1996, the end of 1996.

Geselowitz:

So it’s been 13 years. Do you feel it’s been successful?

Snyder:

I think it’s been reasonably successful. We haven’t eliminated some of the problems, and a couple of the societies that didn’t like us then still don’t like us. But I think it’s done a lot. We’ve come a long way because one of the things I did in the—after I left office, I was a VP—I became a civilian again if you will. I was asked to chair a committee of the Board, an ad hoc committee, to look into whether or not professional activities could be exported from the United States to other parts of the world. And I did make presentations at each of the regional meetings for Regions 8, 9, and 10. Region 7, Canada, already had something going although I did make a presentation there. My thrust was eight, nine, and ten, and then I did a survey of the officers, of the section officers at those regions, so seven, eight, nine, and ten, and we did a survey of, a sample survey of the members in those regions. And the data came back that two-thirds of the members wanted us to do something, and if I recall correctly, Henry Bachman was chair of the Strategic Planning Committee at that time. And I made the presentation to them, and up to that point Henry was not a fan of professional activity. He didn’t think it was necessary, and he thought certainly that outside the United States they didn't want it because they have umpteen different countries, different legislatures, different ways of doing business. They couldn’t be part of what we were doing.

Geselowitz:

Also, a lot of the countries have a country organization that people can belong to, a national organization

Snyder:

Exactly, but in this case after I did the surveys, I went to the strategic planning meeting and made my presentation. Afterwards Henry said, Joel, you’ve convinced me. They do want it, and over a period of time, very slowly because we couldn’t convince the Board to do these things, and we couldn’t convince some of the regional activities boards because they were used to a status quo. So, over a period of time, the first thing I was able to do is I had a number of meetings with people from Region 9 and the IEEE Spectrum magazine people. The first real accomplishment was to get a Latin American job-listing service up and going on the web as well as in Spectrum, and nowadays there’s stuff all over the world. So, some of the things we do in USA don’t export, others do. The biggest topic I spoke about down in South America when I visited there as VP of IEEE USA was giving lectures on how to speak to your government. The first question they asked me was, how do you speak to your government? We haven’t been allowed to. Now, for the first time we’re allowed to talk to them. What do you do? So, I was giving lectures in Argentina, and in Brazil, and a few other places. What do you do when you want to go to the government?

Geselowitz:

So there was that period in the eighties when there was democratization in Latin America?

Snyder:

Yes, this was the eighties and nineties.

Geselowitz:

Right.

Snyder:

And they began to say, hey, we can now talk to our governments. Tell us what you’re talking to them about so we can begin to do the same types of things. So, the interest was peaked in the late nineties, and IEEE began to move in that direction in several aspects. Unfortunately, we still don’t have a good model for professional activities outside the United States, but we’re approaching it. And it will get there. It will get there.

Geselowitz:

And what were you doing in your career at this point while you were serving on the board and being sent all over the world?

Teaching

Snyder:

Well, yeah, that’s a problem. I worked for a number of companies. My first job out of school was with IBM, and I went to work for other companies after that. And I went on my own as a freelance consultant in 1963. So, I was doing that for many, many years. I started teaching part-time, teaching one course a night, one course a semester at night. I guess that was in the late seventies, probably the late sixties I started teaching.

Geselowitz:

And where did you teach.

Snyder:

I taught at C.W. Post College in the Math Department, an Introduction to Computing course. I then taught at New York Institute of Technology. I was an adjunct associate professor there. I there taught lectures on computer—pardon me, electrical and computer technology courses. I have to be very careful. I got thrown out of that place once when I made a big mistake. I told the students the truth.

Geselowitz:

About electrical engineering and technology?

Snyder:

Yes, because the students had been told one way or another that, well, you’re the equivalent of an engineer even though you do technology. I was active in professional registration committees and I served on the National Council of Engineering Examiners writing questions for the PE exams and everything. Well, one day one of the students asked me a question. Why do you use PE after your name? And I explained it. Oh, well can we become PEs? I said sure. What are the requirements? I said, well, you go to an accredited school, which is good, but it’s accredited in technology so your requirement is that after you graduate you must have eight years of experience. If you went to a non-accredited school it would be twelve years. Oh, but you said that is for technology—but we’re engineers. I said, yes, if you went to an accredited school for engineering it would be only four years, but your school is accredited for technology. Well, one of the students went to the dean and complained that the school had lied to them. They are not the equivalent of engineers. They’re slightly different, and I got called into the dean’s office. What did you tell them? I told him. And he says, well, you told the truth, but what you told them was not in the best interest of the school so don’t bother showing up next week for class.

Geselowitz:

Wow.

Snyder:

I was told that’s it, and I walked away from the classroom. I said, well, if they don’t want me, then I sure as heck don’t want them. A year later or two years later I went to teach at Poly as a part-time evening instructor in the graduate school. And then I got asked—a buddy of mine was the chair of the department in Brooklyn. He says, Joel, I got a problem. I need a course covered. Can you do it? Because you’re freelancing, and your time is your own. I said for you I’ll do a favor. I did it, and the next thing I know I’m an adjunct at Poly in Brooklyn.

Geselowitz:

Who was that?

Snyder:

Ed Smith.

Geselowitz:

Ed Smith?

Snyder:

He was the chair of the Computer Science, EE Department, then the Computer Science Department, and he hired me into the Computer Science Department. And then after a couple of years there, they said, okay, well you’re teaching a course. We want you to do something else, so we’ll give you a full-time appointment, but you’ll only come in a couple days a week, two or three days a week, which is what I did. For ten years I came in 2.5 days a week, and they considered me a full-time. I had a fancy title. I had my own office. I had a staff of twelve people working for me. I ended up being Director of Academic Laboratories. I ended up being course director for several courses. I ended up being the person who hires and fires all the adjuncts for the EE Department and I supervised the lab technicians for all the labs as well. So, I ended up doing a lot of things in three days a week, and then I—and this is semi off the record—I made enemies of the guy who became acting head of the department, interim head for a short period of time. And he decided he was out to get me, and my contract was up for renewal. He gave me a new contract—he offered me a new contract with terms so onerous I said, wait a second, I’m a candidate for president of the IEEE. You’re telling me I’ve got to be in school five days a week minimum. I said it can’t be. I said I have approval from the dean, the head of the department the last year and the dean last year that I could do this. I said I wouldn’t—it requires a large time commitment. Well, I’m sorry. So, I quit my job. I wouldn’t sign that contract, and I left Poly. I continued my consulting work in the beginning, and then as my IEEE load increased and increased, my consulting load dropped and dropped until I said, you know, the hell with it, I’m going to retire. That’s it.

Geselowitz:

I’m glad you were in a position to retire. In any of your teaching, did you get involved at all with the IEEE student branches since that’s how you got your start?

Snyder:

Yes, I did. That was under faculty. I was never the faculty member who was the coordinator for them, but I worked with him. It was a colleague of mine, and I worked with them on a number of occasions. And at one point I convinced them to hold an SPAC, Student Professional Awareness Conference, at the school. And one of my students, my star student, was the chair of the IEEE section then, the chapter—student branch is the proper word—and he organized the SPAC, which was a resounding success. It had all the schools in the New York area coming to Poly, and so, yes, I was involved to that extent, and after I left Poly even, I went back a couple of times and made presentations as past president and as president to the student branch. And the students ate that up alive. So, yeah, I continued it.

IEEE Presidency

Geselowitz:

So what was the year you ran for president?

Snyder:

I was president elect in 2000. I ran a couple of times before, actually three times. So, I ran in 1997, 1998, and 1999 and I won in 1999 and became President Elect in 2000.

Geselowitz:

That’s when you retired from consulting?

Snyder:

Yes.

Geselowitz:

So what did you get involved with when you were President Elect?

Snyder:

Mainly working as a liaison between the IEEE Board and other organizations. I attended all the meetings of RAB, and of course TAB, and IEEE-USA. I attended some Standards Activities Board meetings. I went to a couple of conferences. I made a couple of milestone presentations to sections. What else? I also served as liaison with external groups. I met with university people in a few different schools all over the world. When I was President, I did the same thing. One of the big jobs of the President is to be seen, and I was all over the place for these guys. Some of it was very interesting, intriguing. I signed a good number of intra-society agreements while I was president in various countries. I was keynote speaker at a couple of conferences. As President Elect, as President, as Past President—as one of the three P’s you get to do anything your heart desires, and a lot of things your heart doesn’t want to do but you get to do them.

Geselowitz:

Do any of the trips in particular stand out from amongst all those dozens of trips?

Snyder:

A couple are memorable. Some of my South America trips are—I have a lot of fond ties to Region 9, particularly to Mexico and to South America, mainly Brazil, Argentina, Peru. I met a lot of people there and became good friends with many of them. The most memorable visitations and trips, well, let’s see there’s one trip to India I made to New Delhi that stands out in my mind. They put together a conference in my honor of student chapters from seven or eight schools. We met at one of the universities there, and these students put on a show describing what they were doing, and they prepared exhibits for me, and everything that was phenomenal. So, that’s a highlight. Two trips to South America stand out as well. One of my visitations to Peru was presenting of an award up in a town called Piura—which is up in northern Peru—at a small university there. They were presenting a Peruvian award for electrical engineering, and I was asked to make the presentation. As I said, these are good friends of mine. One of them is currently on the foundation, Pepe Valdez. So, he asked me to come there. I went there, made the award, and my recollection is that the greeting from the students of this very small college was the most heartfelt I’ve ever seen. The other trip was when I put up a milestone there.

Geselowitz:

Yeah, we did a power plant in Chivilingo, Chile.

Snyder:

That’s right. The thing that impressed me there was two things. Number one, this is a small, tiny town in the throes of poverty, maybe third world quality, and you walk along the streets, and the only street that was paved was the highway going through it and the highway going to where the mines were, which is where the power plant was. The streets are all dirt. Yet, every morning going to school, we drive through there in the morning going to the plant, the kids going to school were on in uniform, dark skirts or pants, white shirts, spotlessly clean and so well mannered it was ridiculous. They’re so into the educational aspects of it that the kids were perfect, and they had a museum for kids there, a hands-on museum, touchy feely where you play with things and do things, which was as good as anything anywhere in the world, which really turned me on to the power of education. That was interesting. We had a meeting in Japan once where we went to this one shrine, which had the three moneys, see no evil, hear no evil, and speak no evil. There were three of us there, three guys who were campaigning for presidency in one of the years, and one of the fellows said why don’t all three of you pose underneath one of those signs? One of the guys refused to so we let that photo op go by.

Geselowitz:

I was going to say I’d love to see that picture.

Snyder:

So would I. What else was really outstanding? I would say several meetings with the students in a few of the countries, particularly unusual ones, like I was in Bulgaria. It was fantastic. I enjoyed my trips to Moscow. I enjoyed my meetings with the Popov Society. Moscow and St. Petersburg are two of my favorite cities nowadays. I still love Paris, still love Rome. Tokyo’s good. I make the claim that anywhere in the world I want to go to for a vacation, I can call somebody up and meet them for dinner and pick up the conversation where we left off.

Geselowitz:

Just through IEEE.

Snyder:

Just through IEEE. It gave me thousands of friends all over the world, and that to me is a major wonder of being alive and enjoying it. So, that’s one of the best things I got out of it.

Networking

Geselowitz:

I wonder if we don’t sell that aspect strongly enough.

Snyder:

Well, we have to sell the aspect that IEEE has a spectacular networking capability, and the friends you make are not only colleagues, but they become good friends. You get to know people all over the world in a different way, and it’s wonderful. I’ve been to parts of the world where people are at war with each other. Yet at an IEEE meeting, they all sit and talk. I made that comment once at a Region 8 meeting when I was president. There were representatives from sections from three different countries sitting around the table—three countries where the countries were fighting and battling and killing each other—and these three guys were sitting there talking to each other, shaking hands and drinking and breaking bread together. Now, you can’t find that in the U.N., much less anywhere else. But in the IEEE it works. So, to me the IEEE is quite a bit different than any other organization.

Geselowitz:

Well, that actually kind of gets us to your presidential year, but let me start by asking did you have any particular things you wanted to accomplish as president other than to keep the trains running on time and all that stuff?

Snyder:

The biggest thing was to survive. There were a number of very contentious issues when I came into office. We had a problem with the Computer Society, which I helped solve because it overlapped the beginning of my term. We had some major problems with ExCom, which I could not solve, and Ray Finley couldn’t solve. He was my successor. It finally ended up resolving itself, but unfortunately the negative aspects came true.

Geselowitz:

You disagreed about the ownership of property?

Snyder:

There were ownership questions, and their burn rate for finances was horrendous. And the income was rapidly decreasing to the point where the staff business manager Dick Schwartz and others forecasted that in three to five years they’d be bankrupt. And they would have eaten up something like $12 million. In those days that was a heck of a lot of money. This was money that was allocated—partially allocated to the sections and sponsors of the conference, and the conference committee, and the conference organizations were eating it up. And we clamped down on them, threatened to sue them and legally break them up. Ray didn’t want to do that, and the Board said do it, but the fighting was horrendous. And there was threat of lawsuits—lawsuits were filed, and we finally said, okay, let’s back off, not force the issue, and convince them to make some changes, which we did. And it died by itself, but it was a nasty, ticklish time for us. We had some staffing problems at the same time, which resolved themselves over the next year or two. So, it was a tough year. We had the recession also while I was president.

9/11 and After

Geselowitz:

Right, and of course 9/11.

Snyder:

And 9/11, which also hurt our business. I had to go to the board of directors, or to ExCom rather, and we took over the hiring and firing of all of our IEEE employees because we couldn’t afford to keep expanding the way we were. So we ended up passing some motions and giving the President the authority to do certain things. In those days, the by-laws did not specifically call the president the CEO. So, the president was really somewhat limited in what he could do without having a ruling of the Ex Com or the Board. So, I was able to get those rulings to do what I had to do. So, we clamped down. We cut the budget. We stopped hiring. We cut the budget. We made efficiency changes. We reallocated personnel. It made a big difference, kept us going for a while.

Geselowitz:

Now, so you were the first President to hold the title of CEO then?

Snyder:

Actually, no. That didn’t occur until two years later or three years later. The by-laws were not changed to include the term CEO while I was there. I just assumed it.

Geselowitz:

So the Board gave you the authority to do what needed to be done, and later they decided they should formalize this in the by-laws?

Snyder:

Yes, while I was president they talked about it. There were a number of correspondences between myself and Bob Dwyer, our legal counsel, as to what we should do and how we should do it. But it took I think two or three years before it got codified and before enough Board members were convinced to approve it. And then because there was also some change that had to go before the membership to be put before the membership. But like in anything else, it was like pulling teeth. Our board members don’t convince easily sometimes, but it got done.

Geselowitz:

I think that you suggested before I was over emphasizing the tension between global organization and U.S.-based organization, but I think that 9/11 brought out some of those fault lines.

Snyder:

Not in the same way.

Geselowitz:

Because I know the U.S. clamped down on certain countries one could do business with, and we had sections in those countries.

Snyder:

We had sections in those countries, and those countries suffered. We had the U.S. Government rulings, and I sent a letter to every member in those affected countries explaining that they were members in good standing. If they wished to continue paying their dues, they could, but there were problems in our accepting the money and in how we handled it. And we worked out a legal work-around, which allowed us to keep them as members and still keep them in good standing without having to worry about the moneys because you couldn't receive money or ship money there. So, there were a lot of restrictions that were placed on us, and some of our members were furious that we dared put any restrictions on members. I mean, how can you do something? And the answer is very simple. We’re a United States corporation, and we have to obey the laws of the host country, and if we were in your country, we’d have to obey your laws. And as a matter of fact, in many countries IEEE has separate incorporations. Otherwise, we couldn’t do business. I mean this is typical in most of Europe, for example.

Geselowitz:

I see.

Snyder:

So, we had to watch those things, but they were just stumbling blocks. They were not true impediments. They were just stumbling blocks, and they took a little bit of doing on our part and they took a little bit of doing in terms of convincing the membership, hey, relax. We’re not hurting anybody, and work that way. I don’t think it was any sort of a source of rift, at least between the professional aspects and the traditional technical aspects. That did not contribute to it. The biggest thing was five years earlier or eight years earlier in the middle nineties. Then there was a major battle. As I mentioned before, we had a couple of guys in the Computer Society who were so vehemently opposed to IEEE-USA that they were ready to disband us and fire us altogether. I was VP at the time, and we had many a sleepless night trying to iron that one out. But we finally got a solution to it. It was a compromise, and it worked. But it did work.

Geselowitz:

What was the crux of the compromise?

Snyder:

The crux was we did away with the Vice President of Professional Activities. We created a president of IEEE-USA, directly elected, and we gave that person a seat on the ExCom and on the Board. Prior to that the Vice President, of course, had a seat on both. The Computer Society wanted to do away with both of them. We convinced them, no, don’t do that because if you do that, we’re going to ask that you be disbanded also and that you shouldn’t have two representatives any more—the Computer Society has two Division Directors—you should at most have one. So, they began to quiet down a little bit. But that was probably the most active, vehement opposition to us I’d seen in a good number of years.

Geselowitz:

So you talked about, and then when you continued as immediate past president in 2002, you said you still did a lot of the traveling, a lot of liaison work.

Snyder:

A lot of liaison work. I was still presenting awards, milestone plaques. I was still going to signings, still showing up as keynote speaker or welcoming speakers at a couple of conferences. So, things didn’t slow down that much. The number of invitations decreased because I was no longer the person of primary interest, but there were still plenty of things to do. That statue on the wall behind you there was a gift given to me in India. It’s the god Shiva, and when I was at the hotel, they gave it to me. I said how the heck am I going to pack this thing up and bring it home? So, the hotel helped me pack it, and I ship it on the airplane in baggage, of course, because it was too heavy to carry. And when I landed at New York, I have to go through customs and immigration, and for some reason I get to the final station pushing the cart with my bags, and my wife’s bags because she had gone with me, and this monster box, which is all taped up and tied up. And for some reason the customs official who greeted me was not too happy. I don’t know why; I didn’t do anything. I didn’t see anything happen to the person before me, but this lady looks at me and says, and what’s in that box? So, I looked at her straight in the eye, and I said a big, blonde statue of the Indian god Shiva, would you like to open it up and look at it? And she looked at me straight in the eye and said no thank you and let me go right through.

Continued Involvement

Geselowitz:

So after you rotated off the board, you were not the immediate Past President, but a past president—how did you stay involved?

Snyder:

Well, a couple of societies enlisted me. The first one was the Engineering Management Society, which now is a Council. I served on their Board of Governors and as one of their vice presidents for a few years. I also became involved after that with the Industrial Electronics Society, and I was on their conference committee, and I was their chairman for inter-society relations. I generate MOUs for them and contracts between societies. I did that for a few years, and then I was asked to join the Vehicular Technology Society and take over as chair of the Awards Committee, which I’m doing to this day. It’s now my second year.

Geselowitz:

So were those technologies—industrial electronics and vehicular technology—that you interacted with a lot when you were a consultant, so that you got to know the members of those societies?

Snyder:

I didn’t get to know either one of the societies in my activity, but I did do work in those areas. Industrial electronics, of course, most of my work was industrial automation, factory automation, automatic tests, a lot of my work for a good number of years besides the time I spent in aerospace and other things. For vehicular technology, I had a couple of interesting jobs in related fields. I had a contract with Aerospace Corp and the Department of Transportation, and I had my own half-kilometer section out in Pueblo, Colorado, at the DOT Test Center. And I had instrumented this section of track. And I had a trailer, a 20 by probably 20-foot by 60-foot trailer full of computers. And we were monitoring three-car trains with all sorts of failures built into it as they went by. The project was to be able to detect failures before they occur in trains that go by you on the fly, and that was a wayside project. So, I worked on that for a couple of years, two or three years. So, I had some minor background in that. My military work included working on control systems for military aircraft. So, I had some background in that. In industrial electronics, of course, I had three clients who all I did was design automated equipment for their factories. So you cover the ground. When you’ve been in the business as long as I have, you get to work in a lot of different areas. As an example, I built the first removable media disc memory, where you could take the disc out and put it in your pocket. It wasn’t a floppy. It was about a six-inch diameter piece of metal, which was plated, magnetic plating, so you could record on it. It was a magnetic disc, but it was small enough to fit in your jacket pocket, and because it was metallic, you couldn’t destroy it easily. And that was removable, and about a year later, they came out with floppies, which were the size of Victrola play records. But mine was one of the first. We built voice-over data modems, which could transmit voice and data on the same telephone wires. I worked on pacemakers. I built one of the first prosthetic arms. I spent several years doing research on prosthetics for the Veterans Administration. So you get to work in a lot of different areas. At IBM I did software. At AIL, I worked on airborne systems to evaluate navigational devices. At HK, I designed computer circuitry, lots of different things.

Geselowitz:

So, I have two other questions. As you went up through the IEEE volunteer ladder, have you stayed involved with the Long Island Section?

Snyder:

Only up through the time I was Vice President of Professional Activities. The first year I was VP I used to come to some of the meetings here, but after that my workload got so horrendous that I came to fewer and fewer meetings. As President I came to one meeting, as one of the three P’s. I was just too busy with too much else, and to this day, I go to one or two meetings a year that’s all. Down in Florida, which is where I have a winter residence, I’ve been trying to be active. I went to some meetings of the Life Member Chapter down there, but they’ve been very inactive. I’ve been trying to re-activate that section, not having much luck. The guys just don’t give a damn. One guy has been chair of the section now for six years I think or seven years, doesn’t want to give it up; he doesn’t want to do anything but doesn’t want to give it up. And as far as he’s concerned, the world revolves around the academic needs. I went to a meeting there. They called a special meeting I insisted on in June, and I went down there, went to the meeting, and I said, how about plans for meetings, section meetings in September/October? Oh, we should plan something. I said, well, do you have a committee? When are they going to meet? I’d like to join them. Oh, well,—we’ll meet again in September. I said, well, how are you going to meet in September and plan a meeting for September/October? Oh, well, we’ll work something out. It’s not academic. They don’t want to think about it, and I said how may industrial members do we have? The guy didn’t even know. I said look in SAMIEEE You go into the new management system; find out. It remains to be seen whether anything ever gets done.

Geselowitz:

In terms of the Life Members, we find that history motivates them. The life members get interested in history, and you can get them excited in a milestone or something like that.

Snyder:

Yeah, yeah, some of them do. The Life Member Group that I was participating with is the Palm Beach Section. They used to hold meetings, three or four meetings a year, five meetings a year, and they were always interesting. They always had 30, 40, 50 people show up, but a couple of the guys who were doing it, who were organizing the meetings, got tired or sick, and there was nobody to push it. So, one of them said, Joel, will you do it? I said I’m a snowbird. I’m only here four or five months out of the year. I said I can’t organize meetings.

Geselowitz:

Maybe when you move down there full-time.

Snyder:

If I move down there full-time, the question becomes do I want to get active in the Palm Beach Section, although I could go to the neighboring section, which is Fort Lauderdale. I could go to either one I guess because I think you can go to a contiguous section.

Geselowitz:

Right.

Snyder:

So, I’ll play it by ear when I get down there.

Geselowitz:

No rush. I’m not pushing you. I’m not rushing you.

Snyder:

I know. I know.

Snyder:

I know. Another funny experience I had was not in IEEE. I used to be known in the diamond industry. I was building laser-based equipment to drill, cut and saw diamonds and inscribe diamonds. I have equipment in Israel, in Belgium, United States, Japan, other places.

Geselowitz:

South Africa maybe?

Snyder:

No, not in Africa.

Geselowitz:

So they mine there and process elsewhere

Snyder:

Correct. So, I’m going to install a very interesting piece of equipment, not for gem diamonds but for industrial diamonds in Osaka. And I land in the airport there, and I have this big Zero Halliburton aluminum case on wheels with a laser in it and a few other things in it, and I’m going through customs. And of course the guy doesn’t speak any English, or he pretends not to speak English. Now, my client had been smart. He said, Joel, let me give you a letter to take with you introducing you to the company, to the government and to the company. And he puts every honorific he could think of in front of my name and another set of honorifics after my name. This is the doctor, professor, mister, sir, you name it. He put it in there. This guys starts to give me trouble, he wants me to open this case. Now it was packed up with foam so it was compressed. If I opened it up, everything would have spewed out of it. He signals me to open it up. I picked out the letter, and I hand it to him. And as he’s reading it he starts bowing deeper, and deeper until he’s parallel to the ground. Finally, he folds the letter up very carefully, puts it back in the envelope, hands it to me with both hands, and bows to me and goes. So, it pays to know where you’re going, what the local customs are, and my client knew the local customs. Oh, man.

Geselowitz:

So, the other thing I want to ask you about the last—because of your very long, and broad, and successful career—is about the technology economy of Long Island and what’s happened to it over the years.

Snyder:

Long Island for engineering is in many respects a ghost of what it used to be. We had at one point the major state-of-the-art companies here. Most of them are out of business. A few of them are still around, still surviving, but they’re shadows of what they used to be. Airborne Instruments, they went to Cutler-Hammer, then they went to Eaton, and they’re still around but much smaller. Instrument Systems Corporation used to be a major player in government, in aerospace. Today they’re a relatively minor player here. Grumman Aircraft, used to be 35,000 employees. They’re now down to 4,000 or 5,000. The economy on Long Island is not good. We still have some top notch colleges, still have some major employers, but nowhere near what it used to be. It’s no longer a hot-bed center of engineering and technology. It was, but it’s not that way any more. It’s a pity because the base of talented individuals here was enormous, and we’ve allowed it to fritter away. And we’ve allowed most of our industry throughout the country to fritter away, and that’s what worries because God forbid there’s a problem. Remember prior wars, prior battles, prior difficulties, we’ve always been able to tool up and build what we needed to build to survive. We can’t do it anymore, and what’s going to happen to the rest of the world? I don't know. I see the economy as being a very major problem right now, and I see the engineers needed more than ever but ignored more than ever. It’s a pity we don't have more engineers in government, in our Congress and our Senate. We should.

Geselowitz:

Is that something IEEE-USA should be working on?

Snyder:

Well, yes and no. I don’t believe the IEEE should be working on it per se. We already have an IEEE USA fellows program which includes Congressional Fellows, Legislative fellows, and I believe other categories as well, people who are employed for a full year by the government to write laws, to analyze things for the Congressmen and Senators, etc. What I think we should be doing is encouraging more of our members to run for political office. I always make the statement, politicians are generally lawyers who when there’s a problem they try to mediate a compromise. Engineers try to solve problems; they don’t try to mediate a compromise. They try to solve the problems. We need more engineers in government. I personally wanted to run for office, but my wife told me you run for office, you’re out the door. She doesn’t trust politicians one thin dime.

Geselowitz:

What can I say, we’re residents of New York, and look at what the State Senate has been doing for the past several weeks.

Snyder:

It’s a comedy of errors, and look at our governor who is a past lieutenant governor has no successor. And there is really no provision in the state law to appoint a successor. So, if God forbid he were to pass on or have an accident, we would be leaderless. There’d be a major battle. This is really—this is stupidity. Engineers would never do that.

Geselowitz:

Right. Well, I think we’ve covered all of my major questions. I was wondering if there’s anything else you’d like to add about your IEEE career or your years as president for the record so to speak.

Snyder:

A couple of thoughts, I’ve been active at IEEE since I was 17 or 18-years-old, 18-years-old I guess, maybe a little bit more, and I’m a lot older than that now. And I’ve been part of the IEEE since then, but the last 20 years, which includes my local activities and my national/international activities, have been a great joy to me, and I’ve made, as I said before I have made more friends, more good friends through the IEEE than I ever could have working for a company or teaching for a university. The IEEE is part of my life, became part of my life very quickly, and it stayed part of my life. And my wife has come to accept it. At one point she used to joke that if we ever get divorced, she was going to name the IEEE as correspondent. But it’s a spectacular organization. It has the power to do enormous good. I only hope that it continues to do the good that it has done in the past. So, those would be my parting words.

Geselowitz:

That’s terrific. Well, thank you very much. I really appreciate it.

Snyder:

Thank you.