Milestones:Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, 1962: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, 1962 == | == Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, 1962 == | ||

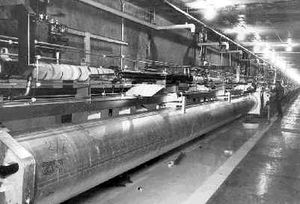

[[Image: | [[Image:Stanford Linear Accelerator Center.jpg|thumb]]Stanford, CA Dedicated February 1984 - IEEE San Francisco Bay Area Council<br>(ASME National Historic Engineering Landmark, with IEEE) | ||

''The Stanford two-mile accelerator, the longest in the world, accelerates electrons to the very high energy needed in the study of subatomic particles and forces. Experiments performed here have shown that the proton, one of the building blocks of the atom, is in turn composed of smaller particles now called quarks. Other research here has uncovered new families of particles and demonstrated subtle effects of the weak nuclear force. This research requires the utmost precision in the large and unique electromechanical devices and systems that accelerate, define, deliver and store the beams of particles, and in the detectors that analyze the results of the particle interactions.'' | ''The Stanford two-mile accelerator, the longest in the world, accelerates electrons to the very high energy needed in the study of subatomic particles and forces. Experiments performed here have shown that the proton, one of the building blocks of the atom, is in turn composed of smaller particles now called quarks. Other research here has uncovered new families of particles and demonstrated subtle effects of the weak nuclear force. This research requires the utmost precision in the large and unique electromechanical devices and systems that accelerate, define, deliver and store the beams of particles, and in the detectors that analyze the results of the particle interactions.'' | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

If any section of the accelerator is out of line, the electromagnetic fields produced in the walls by the passing beam can severely limit the intensity. Controlling this 'beam breakup' effect required precision alignment of the two miles of accelerator. This was solved by mounting four ten-foot accelerator sections on one large aluminum pipe and aligning these four sections with an optical transit in the laboratory. These 40-foot-long sections were then transported into the underground tunnel of the accelerator and connected together. | If any section of the accelerator is out of line, the electromagnetic fields produced in the walls by the passing beam can severely limit the intensity. Controlling this 'beam breakup' effect required precision alignment of the two miles of accelerator. This was solved by mounting four ten-foot accelerator sections on one large aluminum pipe and aligning these four sections with an optical transit in the laboratory. These 40-foot-long sections were then transported into the underground tunnel of the accelerator and connected together. | ||

Fresnel targets, which were built in the end of each 40-foot section, intercepted a laser beam traveling down the center of the pipe. Each 40-foot section was then aligned separately using its own jacking screws. Using this method the accelerator was aligned to be straight within twenty-thousandths of an inch over its two-mile length. <br> | Fresnel targets, which were built in the end of each 40-foot section, intercepted a laser beam traveling down the center of the pipe. Each 40-foot section was then aligned separately using its own jacking screws. Using this method the accelerator was aligned to be straight within twenty-thousandths of an inch over its two-mile length. <br> | ||

<!-- Linear Accelerator --> | |||

<googlemap version="0.9" lat="37.421012" lon="-122.206082" | |||

zoom="10" width="300" height="250" controls="small"> | |||

37.421012, -122.206082, | |||

Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, 1962 | |||

Stanford, Stanford, California, U.S.A. | |||

</googlemap> | |||

[[Category:Nuclear_and_plasma_sciences|{{PAGENAME}}]] [[Category:Particles|{{PAGENAME}}]] [[Category:Particle_accelerators|{{PAGENAME}}]] | [[Category:Nuclear_and_plasma_sciences|{{PAGENAME}}]] [[Category:Particles|{{PAGENAME}}]] [[Category:Particle_accelerators|{{PAGENAME}}]] | ||

Revision as of 19:46, 19 September 2008

Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, 1962

Stanford, CA Dedicated February 1984 - IEEE San Francisco Bay Area Council

(ASME National Historic Engineering Landmark, with IEEE)

The Stanford two-mile accelerator, the longest in the world, accelerates electrons to the very high energy needed in the study of subatomic particles and forces. Experiments performed here have shown that the proton, one of the building blocks of the atom, is in turn composed of smaller particles now called quarks. Other research here has uncovered new families of particles and demonstrated subtle effects of the weak nuclear force. This research requires the utmost precision in the large and unique electromechanical devices and systems that accelerate, define, deliver and store the beams of particles, and in the detectors that analyze the results of the particle interactions.

The basic research tool at SLAC is an intense beam of electrons that have been accelerated by an electric field equivalent to 30 billion volts, making this the most powerful electron beam in the world.

The two-mile linear accelerator produces this field using high-power microwaves traveling through an evacuated waveguide. Electrons injected into one end of this pipe are continuously accelerated by this traveling field to very high energies.

Although the principle is straightforward, the application is not. The engineering problems included manufacturing a thousand sections of precision copper waveguide, aligning these sections over a two-mile length, producing high-power pulsed microwaves, and safely handling the intense high-energy beam of electrons.

The accelerating waveguide, which is basically a long conducting tube about four inches in diameter, was assembled from cylinders and disks that formed individual microwave cavities as shown in the photograph at right.

These cavities, made of high-purity copper, were machined to a precision of about two ten-thousandths of an inch and then brazed in a hydrogen furnace into ten-foot-long sections. Each cavity was then 'tuned' by slightly deforming the outside using hydraulic rams. In the complete accelerator there are nearly 100,000 of these cavities, each brazed to hold high vacuum. This operation required new techniques for mass production to very high standards.

If any section of the accelerator is out of line, the electromagnetic fields produced in the walls by the passing beam can severely limit the intensity. Controlling this 'beam breakup' effect required precision alignment of the two miles of accelerator. This was solved by mounting four ten-foot accelerator sections on one large aluminum pipe and aligning these four sections with an optical transit in the laboratory. These 40-foot-long sections were then transported into the underground tunnel of the accelerator and connected together.

Fresnel targets, which were built in the end of each 40-foot section, intercepted a laser beam traveling down the center of the pipe. Each 40-foot section was then aligned separately using its own jacking screws. Using this method the accelerator was aligned to be straight within twenty-thousandths of an inch over its two-mile length.

<googlemap version="0.9" lat="37.421012" lon="-122.206082"

zoom="10" width="300" height="250" controls="small">

37.421012, -122.206082,

Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, 1962

Stanford, Stanford, California, U.S.A.

</googlemap>