Lewis Latimer: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Mahellrigel (talk | contribs) |

||

| (41 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

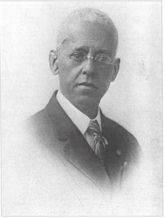

[[Image: | {{Biography | ||

|Image=Latimer.jpg | |||

|Birthdate=1848/09/04 | |||

|Death date=1928/12/11 | |||

|Associated organizations=United States Lighting Company; Edison Pioneers | |||

}} | |||

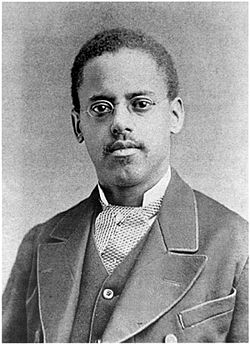

[[Image:250px-Lewis latimer.jpg|thumb]] | |||

Lewis Howard Latimer, the youngest of four children, was born to former slaves, George W. and Rebecca (Smith) Latimer, on 4 September 1848 in Chelsea, Massachusetts. He attended grade school, and the remainder of his education was self-taught. At the age of ten he began working with his father in order to support the family. He had a fabulous appetite for reading, drawing, and learning. | |||

Lewis Latimer's father, George W. Latimer, was born 4 September 1818 in Norfolk, Virginia. He was the son of a white stonemason, Mitchell Latimer, and Margaret Olmstead, a slave owned by Mitchell's brother Edward. In October 1842, George escaped for a second time, taking with him, Rebecca Smith, a slave whom he married in January 1842. Lewis Latimer's parents fled to Boston, Massachusetts, a hotbed of abolitionism. A black minister, Reverend Samuel Caldwell, and others raised four hundred dollars and successfully negotiated for George's freedom. Lewis's father became a freeman on 17 October 1842. In 1858, when Lewis was ten years old, his father abandoned the family, placing the considerable burden of raising four children on his mother. At the age of thirteen, Lewis secured jobs as an office boy in legal offices, including that of noted local attorney, Isaac H. Wright. | |||

Lewis | During the Civil War, Lewis Latimer enlisted in the Union Navy on 16 September 1864 and was discharged honorably on 3 July 1865. He returned to Boston and worked with his mother in housekeeping. Latimer later recalled the legal firm of Crosby, Halsted & Gould Solicitors of American and Foreign Patents was looking for a "colored boy with a taste for drawing." While working as an office boy, he watched the draftsman, bought second-hand books, and learned the skills of drafting. In time, the draftsman allowed Lewis to make some simple technical drawings. Officials at the law firm recognized Lewis's drafting skills and when the draftsman resigned, they appointed him to the post. Thus Lewis became the draftsman at Crosby & Gould. One of his assignments was to make the initial drawings for one of [[Alexander Graham Bell|Alexander Graham Bell’s]] telephone patents. By the late 1870s, Latimer gained considerable knowledge about the technical and legal aspects of patenting. | ||

In 1880, [[Sir Hiram Maxim|Hiram Maxim]], Chief Engineer and Electrician for the United States Electric Lighting Company, who was very impressed with Latimer’s talents as a draftsman, hired him. Latimer took this opportunity to learn about the electric industry. During his tenure with Maxim, he invented an electric lamp with a carbon filament (1881). | |||

In | In 1885, he began his association with [[Thomas Alva Edison|Thomas Edison]], serving as an engineer, chief draftsman, and expert witness on the Board of Patent Control in gathering evidence against the infringement of patents held by General Electric and Westinghouse. He was named an Edison Pioneer in 1918, an elite group of men who worked for Edison. | ||

Latimer married Mary Wilson on 10 December 1873, and they had two children, Emma Jeannette, born in 1883, and Louise Rebecca, born in 1890. | |||

==Notable Patents and Contributions== | |||

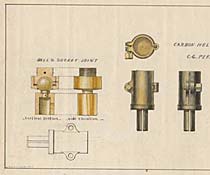

[[Image:Latimer drawing.jpg|thumb]] | |||

#[http://edison.rutgers.edu/latimer/147363.pdf 147,363]: Water closet for railroad cars (1874) | |||

#[http://edison.rutgers.edu/latimer/247097.pdf 247,097]: Improvement to electric lamp (1881) | |||

#[http://edison.rutgers.edu/latimer/252386.pdf 252,386]: Process for manufacturing carbon filament (1882) | |||

#[http://edison.rutgers.edu/latimer/255212.pdf 255,212] [[Arc Lighting|Arc light]]: globe support (1882) | |||

#[http://edison.rutgers.edu/latimer/334078.pdf 334,078]: Apparatus for cooling and disinfecting (1886) | |||

#[http://edison.rutgers.edu/latimer/557076.pdf 557,076]: Device for locking hats, coats and umbrellas on hanging racks (1895) | |||

#[http://edison.rutgers.edu/latimer/781890.pdf 781,890]: Lamp fixture (1910) | |||

In his patent role, he was responsible for preparing the mechanical drawings for Alexander Graham Bell’s patent application for his telephone. Thomas Edison took note of his work for Bell and on the light bulb and hired him in 1884. Latimer, in fact, holds the distinction of being the only African American member of the Edison Pioneers | In his patent role, he was responsible for preparing the mechanical drawings for Alexander Graham Bell’s patent application for his telephone. Thomas Edison took note of his work for Bell and on the light bulb and hired him in 1884. Latimer, in fact, holds the distinction of being the only African American member of the Edison Pioneers. | ||

He continued to work on electric lighting, and in 1890 published Incandescent Electric Lighting, a technical engineering book that became | He continued to work on [[Electric Lighting|electric lighting]], and in 1890 published Incandescent Electric Lighting, a technical engineering book that became a standard guide for lighting engineers. | ||

== | ==Retirement== | ||

He retired in 1924 at the age of | He retired in 1924 at the age of seventy-five. He passed away at his home in Flushing, New York on 11 December 1928, at the age of eighty. When Latimer died, the Edison Pioneers attributed his “important inventions”-- he held eight U.S. patents-- to a “keen perception of the potential of the electric light and kindred industries.” The Edison Pioneers published an obituary that included the following testimonial: | ||

“He was of the colored race, the only one in our organization, and was one of those to respond to the initial call that led to the formation of the Edison Pioneers, January 24th 1918. Broadmindedness, versatility in the accomplishment of things intellectual and cultural, a linguist, a devoted husband and father, all were characteristic of him, and his genial presence will be missed from our gatherings.” | “He was of the colored race, the only one in our organization, and was one of those to respond to the initial call that led to the formation of the Edison Pioneers, January 24th 1918. Broadmindedness, versatility in the accomplishment of things intellectual and cultural, a linguist, a devoted husband and father, all were characteristic of him, and his genial presence will be missed from our gatherings.” | ||

== | ==Further Reading== | ||

[https://reach.ieee.org/multimedia/lewis-h-latimer-electrical-pioneer-and-inventor-a-seldom-told-history/ Lewis H. Latimer, Electrical Pioneer and Inventor, a Seldom-Told History], IEEE REACH Program | |||

Rayvon Fouché, ''Black Inventors in the Age of Segregation: [[Granville T. Woods: Improving Railway Communications|Granville T. Woods]], Lewis H. Latimer, and Shelby J. Davidson''. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003. | |||

Louis Haber, ''Black Pioneers of Science and Invention''. | |||

New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1970. | |||

Robert C. Hayden, ''Eight Black American Inventors''. | |||

Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1972. | |||

Aaron E. Klein, ''Hidden Contributors: Black Scientists and Inventors in America''. | |||

Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1971. | |||

Carroll Pursell, ed., ''A Hammer in Their Hands: A Documentary History of Technology and the African-American Experience''. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2005. | |||

Bruce Sinclair, ed., ''Technology and the African-American Experience: Needs and Opportunities for Study''. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004. | |||

Bayla Singer, ''Inventing a Better Life: Latimer's Technical Center, 1880-1928''. New York: Queens Borough Public Library, 1995. | |||

Ivan Van Sertima, ed. ''Blacks in Science: Ancient and Modern''. | |||

New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transition Books, 1984. | |||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Latimer}} | |||

[[Category: | [[Category:Electric_power_systems]] | ||

[[Category:Engineering_and_society]] | |||

[[Category:African-American_pioneers]] | |||

Latest revision as of 01:45, 5 October 2023

- Birthdate

- 1848/09/04

- Death date

- 1928/12/11

- Associated organizations

- United States Lighting Company, Edison Pioneers

Biography

Lewis Howard Latimer, the youngest of four children, was born to former slaves, George W. and Rebecca (Smith) Latimer, on 4 September 1848 in Chelsea, Massachusetts. He attended grade school, and the remainder of his education was self-taught. At the age of ten he began working with his father in order to support the family. He had a fabulous appetite for reading, drawing, and learning.

Lewis Latimer's father, George W. Latimer, was born 4 September 1818 in Norfolk, Virginia. He was the son of a white stonemason, Mitchell Latimer, and Margaret Olmstead, a slave owned by Mitchell's brother Edward. In October 1842, George escaped for a second time, taking with him, Rebecca Smith, a slave whom he married in January 1842. Lewis Latimer's parents fled to Boston, Massachusetts, a hotbed of abolitionism. A black minister, Reverend Samuel Caldwell, and others raised four hundred dollars and successfully negotiated for George's freedom. Lewis's father became a freeman on 17 October 1842. In 1858, when Lewis was ten years old, his father abandoned the family, placing the considerable burden of raising four children on his mother. At the age of thirteen, Lewis secured jobs as an office boy in legal offices, including that of noted local attorney, Isaac H. Wright.

During the Civil War, Lewis Latimer enlisted in the Union Navy on 16 September 1864 and was discharged honorably on 3 July 1865. He returned to Boston and worked with his mother in housekeeping. Latimer later recalled the legal firm of Crosby, Halsted & Gould Solicitors of American and Foreign Patents was looking for a "colored boy with a taste for drawing." While working as an office boy, he watched the draftsman, bought second-hand books, and learned the skills of drafting. In time, the draftsman allowed Lewis to make some simple technical drawings. Officials at the law firm recognized Lewis's drafting skills and when the draftsman resigned, they appointed him to the post. Thus Lewis became the draftsman at Crosby & Gould. One of his assignments was to make the initial drawings for one of Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone patents. By the late 1870s, Latimer gained considerable knowledge about the technical and legal aspects of patenting.

In 1880, Hiram Maxim, Chief Engineer and Electrician for the United States Electric Lighting Company, who was very impressed with Latimer’s talents as a draftsman, hired him. Latimer took this opportunity to learn about the electric industry. During his tenure with Maxim, he invented an electric lamp with a carbon filament (1881).

In 1885, he began his association with Thomas Edison, serving as an engineer, chief draftsman, and expert witness on the Board of Patent Control in gathering evidence against the infringement of patents held by General Electric and Westinghouse. He was named an Edison Pioneer in 1918, an elite group of men who worked for Edison.

Latimer married Mary Wilson on 10 December 1873, and they had two children, Emma Jeannette, born in 1883, and Louise Rebecca, born in 1890.

Notable Patents and Contributions

- 147,363: Water closet for railroad cars (1874)

- 247,097: Improvement to electric lamp (1881)

- 252,386: Process for manufacturing carbon filament (1882)

- 255,212 Arc light: globe support (1882)

- 334,078: Apparatus for cooling and disinfecting (1886)

- 557,076: Device for locking hats, coats and umbrellas on hanging racks (1895)

- 781,890: Lamp fixture (1910)

In his patent role, he was responsible for preparing the mechanical drawings for Alexander Graham Bell’s patent application for his telephone. Thomas Edison took note of his work for Bell and on the light bulb and hired him in 1884. Latimer, in fact, holds the distinction of being the only African American member of the Edison Pioneers.

He continued to work on electric lighting, and in 1890 published Incandescent Electric Lighting, a technical engineering book that became a standard guide for lighting engineers.

Retirement

He retired in 1924 at the age of seventy-five. He passed away at his home in Flushing, New York on 11 December 1928, at the age of eighty. When Latimer died, the Edison Pioneers attributed his “important inventions”-- he held eight U.S. patents-- to a “keen perception of the potential of the electric light and kindred industries.” The Edison Pioneers published an obituary that included the following testimonial:

“He was of the colored race, the only one in our organization, and was one of those to respond to the initial call that led to the formation of the Edison Pioneers, January 24th 1918. Broadmindedness, versatility in the accomplishment of things intellectual and cultural, a linguist, a devoted husband and father, all were characteristic of him, and his genial presence will be missed from our gatherings.”

Further Reading

Lewis H. Latimer, Electrical Pioneer and Inventor, a Seldom-Told History, IEEE REACH Program

Rayvon Fouché, Black Inventors in the Age of Segregation: Granville T. Woods, Lewis H. Latimer, and Shelby J. Davidson. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.

Louis Haber, Black Pioneers of Science and Invention. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1970.

Robert C. Hayden, Eight Black American Inventors. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1972.

Aaron E. Klein, Hidden Contributors: Black Scientists and Inventors in America. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1971.

Carroll Pursell, ed., A Hammer in Their Hands: A Documentary History of Technology and the African-American Experience. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2005.

Bruce Sinclair, ed., Technology and the African-American Experience: Needs and Opportunities for Study. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004.

Bayla Singer, Inventing a Better Life: Latimer's Technical Center, 1880-1928. New York: Queens Borough Public Library, 1995.

Ivan Van Sertima, ed. Blacks in Science: Ancient and Modern. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transition Books, 1984.