First-Hand:Bing Crosby and the Recording Revolution: Difference between revisions

Rrphillips (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Rrphillips (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 131: | Line 131: | ||

The Mark II version used the same top plate as that of the Mark I, but it was modified for one inch tape. It still operated at 360 ips with the early version of the tight loop drive. Jack Mullin and Wayne Johnson had decided to build the Mark II system before the 11 November demonstration and were actively engaged in its construction. When I started at BCE they were testing various head stacks and working with William Wetzel at 3M to improve the tape quality for the recorder. It was obvious that main problem was how to increase the recorded bandwidth on the tape. We would find out over the next months that there was a lot that was not known about how the head-tape process works. | The Mark II version used the same top plate as that of the Mark I, but it was modified for one inch tape. It still operated at 360 ips with the early version of the tight loop drive. Jack Mullin and Wayne Johnson had decided to build the Mark II system before the 11 November demonstration and were actively engaged in its construction. When I started at BCE they were testing various head stacks and working with William Wetzel at 3M to improve the tape quality for the recorder. It was obvious that main problem was how to increase the recorded bandwidth on the tape. We would find out over the next months that there was a lot that was not known about how the head-tape process works. | ||

A discussion over using a rotary head approach to that of longitudinal had taken place, and there was much doubt that the rotary head would work. It also would have been difficult for the BCE group to implement it because of our lack of the mechanical facilities to build one. The longitudinal approach was selected with multiple tracks. Instead of using a rotary head, the multiple tracks were electronically scanned. The Mark II system had | A discussion over using a rotary head approach to that of longitudinal had taken place, and there was much doubt that the rotary head would work. It also would have been difficult for the BCE group to implement it because of our lack of the mechanical facilities to build one. The longitudinal approach was selected with multiple tracks. Instead of using a rotary head, the multiple tracks were electronically scanned. The Mark II system had 12 tracks recorded on the 1 inch tape. Ten of the tracks were used for the video, and the other two, one on the top of the tape and one on the bottom, were used for audio, sync and reference signals. | ||

The video signal in the record subsystem was sampled with the rate tied to the video sync signal. These samples or pulses were sequentially recorded across the 10 video tracks. For each set of 10 samples the polarity of the recorded pulse was reversed. This was done to prevent a bias on the tape. The result was a series of pulses recorded on each track on the tape alternating in polarity. The amplitude of the recorded pulse was equal to the amplitude of the video sample, and each channel had a 1 MHz bandwidth. | The video signal in the record subsystem was sampled with the rate tied to the video sync signal. These samples or pulses were sequentially recorded across the 10 video tracks. For each set of 10 samples the polarity of the recorded pulse was reversed. This was done to prevent a bias on the tape. The result was a series of pulses recorded on each track on the tape alternating in polarity. The amplitude of the recorded pulse was equal to the amplitude of the video sample, and each channel had a 1 MHz bandwidth. | ||

Revision as of 02:22, 25 August 2013

Contributed by: Robert R. Phillips, Life Member

Introduction

In November of 1951 I quit my job in television in Los Angeles due to the conflict with my high school classes. I could no longer spend time with the remote crews doing live broadcasts but had to live in the dull world of film control on weekends. With the remotes I put in microwave links, repaired TV cameras and installed sound and video equipment. In film control there were only western movies and commercials, and the only excitement came when the film broke.

When I left, one of the directors that worked the remotes gave me a slip of paper with an address, 9030 Sunset Blvd., and a name, Jack Mullin. The next day I went to the address and asked for Jack Mullin and found that he was expecting me. The director was a friend of Frank Healy who was the head of the Electronic Division of Bing Crosby Enterprises. He told Frank about my work at the TV station. John T. (Jack) Mullin was the Chief Engineer, and had decided to hire me based on the recommendation of the director. They knew more about me than I did. The job was to do electronic bench work for Jack Mullin because he had broken his arm. It was to be for two weeks or until his broken arm healed, but the two weeks turned into six years.

The work involved building the first practical video recorder so that Bing Crosby could record his TV shows on magnetic tape just as he was doing with his radio programs. I was the fourth member of the team that consisted of Jack Mullin and Wayne Johnson. The third member was Gene Brown who was the machinist. About a week before, they had demonstrated to the news media what has been described as the first TV picture to have been recorded on tape. All of the main Hollywood press was there, and now the pressure was on to produce the recorder. However, before going into the development of the video recorder it is important to understand the events that led up to this project.

The Audio Years

Over the months after I started working for Jack Mullin, he became my mentor and took me under his wing. He had been the person that had put the Bing Crosby radio show on magnetic tape and with Bing developed the art of editing the tape. Jack not only described to me these events, but took me to see the recording studios and equipment. He also taught me how to record and edit magnetic tape, and that prepared me to be an alternate editor for the radio show. Jack was now full time on the video tape development, and others had taken over the recording and editing work. The years of recording the radio show laid the ground work for the video tape development.

Bing Crosby was one of the pioneers of the radio music show. Beginning in 1935 the “Kraft Music Hall” on the NBC Red Network was a standard. It was a quality live production that held a high position in the ratings over the years. However, the summer of 1945 was a turning point in this standard. Bing decided that doing a live show every week was too demanding, and it did not permit him to pursue his other interests and to be with his family. During one period the show had to be done live twice, once for the east coast and once for the west coast, which also added to the work load. It also was confining, since it all had to be done within a certain regime that took away Bing’s casual side. The adlibs and jokes had to be done according to the script; there was no editing to remove mistakes.

The Bing Crosby show was aired on the elite Red Network of NBC that would not permit recorded shows; they had to be live broadcasts. So, the 1945 – 1946 “Kraft Music Hall” program began without Bing because of the dispute. The show went on, and NBC and Kraft sued him for not appearing. He returned to finish the season beginning with the 7 February 1946 program, but that was the end of Bing on the NBC Red Network. This time Bing had set his mind to having a prerecorded production. However, his current Bing Crosby Productions organization headed by his brother Everett did not have the talent to establish a prerecorded show operation and the technical support it needed. In December of 1945 Bing hired Basil Grillo to help him with this task and improve the operation of Bing Crosby Productions.

In 1941 the US Government broke up the NBC empire and made it sell its Blue Network. NBC had its sophisticated programs on the Red Network and the other features like jazz on the Blue Network. In July 1943 NBC announced the sale of its Blue network, but it took several years for ABC to develop its own programs. They shared the NBC facilities at Sunset and Vine in Hollywood until at least 1948. After the breakup ABC needed programs with high ratings and the upcoming 1946 – 1947 season was no exception. They told Bing that if he joined ABC he could record his show but the quality had to be equal to the live broadcast. It was to be a 30 minute show known as the “Philco Radio Time” program.

A number of events happened during January 1946 before Bing accepted the ABC offer. Bing Crosby Enterprises was reorganized, and a division of it was dedicated to the production of the prerecorded radio show. It included a person, Francis (Frank) Healey, to supervise the technical parts of the production. Prior to this Bing did not have his own technical staff, since the NBC engineers provided that support. By the end of January 1946, Bing had settled with NBC and was well on the way to having his own prerecorded show on ABC.

The new 1946 – 1947 “Philco Radio Time” program began with Bing Crosby recording his show on transcription disks using the NBC recording facilities assigned to ABC and supervised by Frank Healey. However, all was not well with this new production. The recordings on the disks lacked the quality of the live show and the editing process was difficult. The show was done as a live production, but with additional recorded material that could be used if there was a problem. While it took two disks (15 minutes each) for the thirty minute show, the recordings were edited before the show was played at the appointed time on the ABC network.

The prerecorded show permitted changes to be made if Bing or his staff did not like something in the show. The sponsor also was known to require changes that could not be done with a live show. The editing process was difficult, since it required recording from one disk to another several times. At least two or three playback units were required to permit the different parts to be merged on to a new recording disk, and with each copy the sound quality dropped. At times this process took over forty disks and many days to complete the edit. The result was the recorded show was less than desirable, and the radio audience noticed the difference. The ratings dropped, and ABC began to question if they should not return to the live broadcast.

The Recording Revolution

While the Crosby show was struggling with the disk recordings, a new technology had arrived. Jack Mullin had returned from his World War II service with parts for two German Magnetophon magnetic tape recorders that he had shipped back in mail sacks over a number of months. Instead of going back to the telephone company, he joined a friend, William Palmer, in a recording and movie business. William Palmer had a machine shop where they restored and modified the Magnetophon. Jack made new electronics using standard American parts and replaced the DC bias with AC bias to improve the tape signal-to-noise and added pre-emphasis for the high frequencies. These rebuilt Magnetophon recorders were then used in their recording business.

In May 1946 Jack Mullin demonstrated the modified Magnetphon recorder at an IRE (IEEE) show in San Francisco with the help of William Palmer. This demonstration caused a number of people to take notice of the quality that could be obtained from a magnetic tape recorder. There were other tape recorders at that time, but none of them had the outstanding quality of the rebuilt Magnetophon. During the following months William Palmer set up a number of demonstrations of the recorder for Jack to various movie, recording and broadcast people. The demonstrations showed that the recorder could reproduce sound as if it were live. Not only that, the magnetic tape could be edited by cutting it with a pair of scissors and splicing it with Scotch tape.

These demonstrations were more of a novelty to the industry than a major step forward. After all there were only two recorders and only 50 rolls of tape that no longer was made. The movie companies had made other agreements for their sound tracks, and the recording companies were happy with their recording process. During the demonstrations in the summer of 1947 Frank Healey, who was involved with technical production of the Crosby show, heard a demonstration and encouraged Murdo McKenzie, the producer of the Bing Crosby show, to investigate them for the show. Murdo arranged for a demonstration in San Francisco where Jack and Bill Palmer had their business. This demonstration was after the bad experience with the disk recordings, and Crosby now was faced with the prospect of finding a new way of recording the show or reverting to live broadcasts again. Murdo was so impressed with the tape process that he arranged for Bing to hear the demonstration, which took place about the first of August 1947 in Los Angeles. When Bing heard the sound quality and saw the editing, Jack Mullin was asked to do a test recording of the first Bing Crosby show of the 1947 – 1948 season. It was only a week way, and the Crosby people expressed concerns that Jack had only two recorders and a limited amount of tape. There needed to be way forward other than just the Magnetophon.

Jack had made an agreement with Colonel Ranger of Ranger Industries a year earlier to provide him with information so that Ranger could build a version of the Magnetophon and supply tape for it. Tests had shown that the Minnesota Mining (3M) tape would not work with the German recorder. By this time 3M had developed a black oxide plastic backed tape that evolved from their paper backed tape. It was the Scotch Magnetic Tape No. 100 designed for the Brush recorder, which was an early tape recorder. However, the Magnetophon needed a tape that could record a stronger magnetic field and have a better signal-to-noise ratio. The research group at 3M realized this need and set out to develop a higher grade tape using a red oxide, not knowing what the target machine would be. During this period Ampex also had decided to build a broadcast quality tape recorder and asked Jack for assistance, but Jack could not help due to the agreement with Colonel Ranger. As the date for the Crosby recording session approached the tension grew. Colonel Ranger did come to Los Angeles with his two recorders but no new tape. His tape recorders were set up along side the Magnetophon recorders in the recording department of NBC who was still supporting ABC. The show was held on the evening of 10 August 1947, and the moment of truth had come. The NBC engineers recorded the show on the standard disk lathes, and Jack Mullin and Colonel Ranger also recorded on their respective machines. Murdo asked Ranger to play his recording first, and it was terrible with distortion and noise. Jack was next, and history was made. The first radio show to be recorded on magnetic tape was broadcast on 1 October 1947.

Jack, who was still working for Palmer, was given an old studio and control room in the NBC (ABC) facilities where he could set up his machines and do the recording and editing of the show. It also served as his office. The 1947 – 1948 season was the first time a radio program was aired from a magnetic tape recording even though the program was transferred to disk for broadcast. This transfer was due to the need to preserve the tape and insure that a tape break would not disrupt the broadcast. The quality of the show had improved even though disks were used, since the show was only transferred in final form and not edited on the disks. However, more important, the ratings of the show improved and the prerecorded show was preserved. The first step had been taken, but a bigger problem still needed to be addressed – new recorders and tape.

Alexander M. Poniatoff, the head of Ampex, heard one of the early demonstrations of the Magnetphon. He was in need of a new postwar product and was so taken by the recorder he decided to build one. He put his chief engineer, Harold Lindsay, in charge of the project and asked Jack Mullin to help them. Unfortunately Jack had already made the agreement with Colonel Ranger by that time, but Ampex decided to go ahead with the project anyway. After the poor showing of his recorders to the Crosby group, Colonel Ranger was persuaded by them and Jack Mullin to give up his agreement with Mullin. Jack was now free, and a call was placed to Ampex in October 1947. Minnesota Mining (3M) also was brought in as the tape supplier.

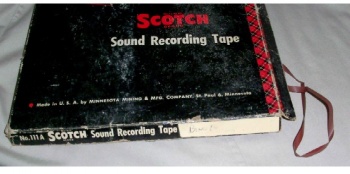

Ampex by the spring of 1948 had developed their first prototype, but lacked finances to bring it to market. The banks did not have any idea about venture capital at that time. Pressure once again began to build because the Bing Crosby show needed new recorders and tape for the 1948 – 1949 season. Everyone was convinced that Ampex was the answer, and Bing sent them a check for $50,000 in just an envelope without any cover letter. It was what Ampex needed to begin production of the Ampex 200. In late 1947 Jack Mullin visited Minnesota Mining (3M) to see if they could provide the required magnetic tape to work with the Magnetophon and the future Ampex recorder. By then they had started development of their new red oxide tape that would work with the Ampex recorder. Jack Mullin began to work with Robert Herr and William Wetzel of 3M conducting tests to help develop a high quality magnetic tape for audio recording. His work focused on the dropout rating, frequency response and signal-to-noise for the different test tapes that 3M produced. The result was the Scotch Magnetic Tape No.111 that later evolved into the No. 111A. For these efforts by Bing and Jack, Bing Crosby Enterprises (BCE) was awarded in 1948 the distributorship west of the Mississippi River for the Ampex recorders and the 3M tape. The Electronic Division of BCE under Frank Healey was given responsibility to market and service these products. The division began to grow when Jack Mullin left Palmer to become its chief engineer in August 1948 to support the development work with Ampex and 3M and in 1949 with the addition of a salesman, Tommy Davis.

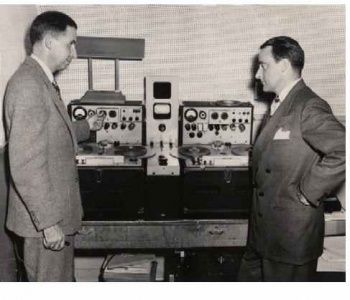

Harold Lindsay led the team to produce the Ampex 200 for Alex Poniatoff and Bing in the 1948. It was housed in a polished black wood console with a stainless steel top that caused it to be called the most beautiful recorder to be made. The Crosby show received the first two of them, serial numbers 1 and 2, in time for the 1948 – 1949 season. Later the only two portable Ampex 200 recorders built, serial numbers 13 and 14, were delivered. Each of them consisted of two wooden boxes with handles. It took at least two people to carry each case, but they were taken everywhere the Crosby show went during the later part of the 1948 -1949 season, even to Canada. Jack Mullin described how they had to push and pull the four boxes up a spiral staircase to reach one of the upper dressing rooms where the recorders were set up. The audio mixing was done at the stage level using the RCA OP-6 and OP-7 equipment. The output was fed over a telephone line to the recording location.

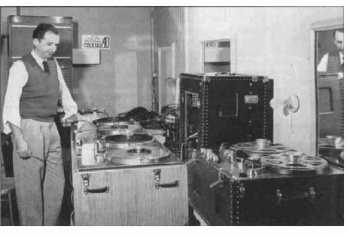

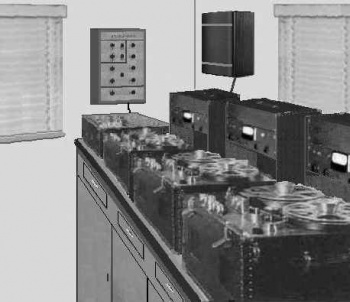

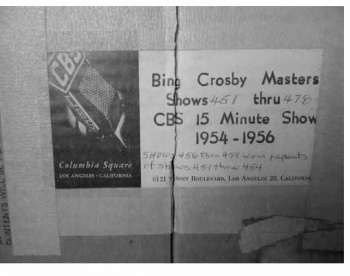

By the 1949 – 1950 season the Bing Crosby show had moved to CBS, and BCE had to establish its own recording-editing facility. It was a small facility located in the CBS Columbia Square Complex at 6121 Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood. It was on the second floor in the east wing of the complex. The recorders were located in the front of the building. There were two windows that were open most of the time, and people on Sunset Boulevard could hear the editing process. The three Ampex 300 recorders were on a waist-high shelf with a special tape speed control unit and acoustical equalizer at one end. In the hallway outside the room, there were shelves of indexed tapes of past recording sessions. By 1950 others like Robert McKinney were involved in the recording and editing of the show. In Hollywood the live show was done at the CBS studios and in a theater behind CBS. The microphone placement and mixing of the show was done by Norm Drews. He was a true professional held in high esteem by Jack Mullin. It has been said that the balance of the shows recorded was outstanding. There were no multiple tracks, just one channel that was fed to the recorders.

Those of us in the recording room had no visible contact with what was happening. I used to sing along with Bing during the recording sessions, since I was the only one there at times. I may have sung more “duets” with him than most people, but it helped to learn his phrasing for editing.

During the first two seasons that used the magnetic tape recorders, the Crosby radio show was recorded in front of a live audience when Bing was available. There were recorded rehearsals, but the editing process was limited by having only two recorders. The first season that was recorded on the old Magnetophon tape had to be transferred to transcription disks because of concerns about the old tape breaking. With the new Ampex recorders and 3M tape, this transfer was no longer required, but the editing was still limited by having only two Ampex 200 recorders.

With the recording of the show, Bing was more relaxed and the audience had more fun with the adlibs, since mistakes could be repaired. The quality was equal to a live show, and the broadcast version was mistake free. With the portable recorders the show also could be taken on the road, if Bing wanted to travel. By early 1949 Ampex had begun to produce the Ampex 300, which was smaller and lighter than the Ampex 200. The big plus was that the Bing Crosby show now had three recorders for the 1949 – 1950 season. These changes opened the door to new innovation, and the Crosby show did not lose time in coming up with new ways to record a radio show.

The Development of the Recording Art

With three recorders Bing, Murdo and Jack set out to see how the show could move away from the basic live audience format. No one had done this type of program before; so these three men were establishing a new art form. During the previous seasons the show was done live and recorded on tape. These shows could be recorded when Bing had the time, and more than one program was recorded during these sessions. However, only limited editing could be done, since there were only two tape recorders. There were others during this period editing tape, but they were using recorders that were intended for the general market. The high quality magnetic tape recordings of radio programs took tape editing to another level.

There were a number of issues that arose as a result of using tape. With the higher bandwidths of the new Ampex recorders it was possible to hear things that were hidden by the lower quality recorders. There were problems due to timing (or tape speed) and wow and flutter that had to be resolved. In addition, the tape also caused dropouts due to imperfections in the oxide that was coated on the plastic backing. To solve this problem Minnesota Mining (3M) was trying different coating techniques for their 111 audio recording tape, and Jack Mullin would test each new batch to determine the dropout rate. After a number of trials 3M produced the 111A tape that became the industry standard.

Since Bing did not read music and sang by ear, one take of a song could be in a different key from the second take. This change in pitch posed a problem when using segments from different recording sessions to make one complete piece of music. Today matching the pitch is easy with digital technology, but in 1950 it was different. To do the matching one tape was slowed down and the other was speeded up until the pitch was the same. However, the change in tape speed led to timing problems; so after the splice was made the tape was then slowly returned to its normal speed. Unless one was listening very closely it was not detectable. With the advent of the Ampex 300, Jack Mullin worked with Ampex to develop a unit to work with the Ampex 300 recorders that produced a 100 kHz signal and process it on playback. The unit then controlled the speed of the Ampex 300 capstan motor so the 100 kHz signal was correct. Not only did it fix the timing problem, but it was able to correct some of the low frequency wow effects. It was now possible to record a tape on one machine and play it back on a different machine without speed changes that caused changes in the pitch of the music. It also was used to change the tape speed to match the different pitches.

Another major problem was not being able to play from two machines and record on a third. The ability to fade from one program segment to another was limited. These edits had to be preplanned in the recording process, but at times long diagonal cuts were made that would allow one segment to fade and the other to get louder. This process was difficult and was not used unless it was the last resort. The Magnetophon recordings were made at 30 inches per second (ips), which made the long cuts impossible. The Ampex 200 operated at both 30 and 15 ips while the Ampex 300 normally operated at both 15 and 7.5 ips. At these lower speeds the long cuts were possible.

With the high speeds, the normal cuts were made with a pair of scissors and Scotch tape. In most cases it was possible to cut the tape as it was running since there was a lot of room for error. Jack Mullin had great ear-to-hand coordination and could make the cuts even at 15 ips. I used to do it as well, but not with the accuracy that the Jack had. When it came to cutting a note or syllable it required the tape to be stopped and moved back and forth until the correct spot could be located. The head gate was then opened and the tape cut at the playback head gap. Jack and I did not use any splicing blocks since we were able to cut the tape at the same angle; however, in most cases the ends of the taped were overlapped. This overlap caused problems when rewinding the tape since the splices would get caught going through the head gate. The tape in the early days was put together using Scotch tape that would stick to the other winding of tape on the reel. To prevent the sticking, talcum powder was used, and it is still present today in the early tapes being restored. About 1951 3M produced a splicing tape that eliminated the sticking problem. One of the great edits of Jack Mullin was made late at night on 2 November 1948 when it was found out the Truman had won the election instead of Dewey. When the show was recorded, Bing said that Dewey had won. With no “Truman” recorded by Bing, Jack had to manufacture the name using the existing tape and do it with the Ampex 200 recorders.

When the Crosby Show received its three Ampex 300 machines, the editing process changed as did the format of the radio show. The early radio programs were recordings of live shows with little editing, but the later shows were assembled from many different recordings. One of the new innovations of this period was the introduction of recorded audience reactions. Fake laughter always had been around. It was added by turning the volume up and then fading it down. The same laughter was used every time, and it became known as “canned laughter.” After one live show where the guest and Bing caused much audience reaction that had to be cut, Jack Mullin was going to throw out the rejected tape. Bing happened to be there at the time and told him to save it for future use. Thus the new “laugh track” was started. By the time I began to edit, the “laugh track” had grown to forty-two different segments. These ranged from great outbursts of laughter to the groans of the audience. The orchestra had their reactions as did the lady in the balcony.

The radio program by now was scripted down to each segment of tape. These segments came from many different sources that had to be matched. The acoustics of Bing’s ranch house in Elko had to match with the characteristics of the studios in Hollywood and New York. The Marine Auditorium in San Francisco had to agree with a theater in Canada. To match the acoustics, Jack Mullin built a filter box where the audio characteristics could be altered and echo added if required. When a recording session was held, material was recorded for four to six shows. Portions of these sessions also included a live audience, and parts of it would be used in other shows.

Separate segments also were recorded to keep the shows current. These were made wherever Bing happened to be, and the same applied to the guests on the show. The acoustics of Bing’s ranch in Elko and remote studios had to be accommodated in the editing process. Besides these different sources, a large library of recorded material was created that was crossed referenced by date, artist and subject. This catalogue made it possible to reuse old recordings and cut back on the new recording sessions.

Each radio program was assembled from the different sources according to the script. During the editing process different short segments of tape were attached to a line that was above the recorders with the number of the segment, but the longer ones were kept on reels that were numbered. Once the music segments were edited and put into one continuous program, the voice segments were added and the program was cut to the proper time. This cutting of the program involved the editing of verses, refrains or portions of them so that the program was the correct length to be broadcast. The audience reactions were then added that involved listening to the program and deciding what type of reaction was required. Bad jokes got bad responses and good ones got good ones. However, the process somewhat involved the ear of the beholder and arguments occurred between the editors. Murdo made the final decision. He sat on a bar stool behind the editors with an old Paris taxi horn attached to its side. To get the editors attention he would squeeze its large bulb. We had the speakers turned up so loud, it was difficult to hear him. Besides the standard reactions to the banter between the parties on the show, other reactions were injected where it appeared that something was happening with the orchestra or on the stage.

This editing might be described as the high point of recorded shows. Many of these editing techniques then were used by the radio networks and record companies. The Bing Crosby radio show during its last few seasons produced shows that never happened the way they were heard by the radio audience. This art form was created by the talents of Bing Crosby and Jack Mullin. It was made possible by the recorders produced by Ampex and the magnetic tape manufactured by Minnesota Mining (3M).

The Desire for Video Recording

By 1953 Bing was facing a new problem, television. He was being asked to do television shows instead of radio, but there was no easy way to record a television program as he was doing with his radio show. In 1951 Bing asked Jack Mullin if he could record television on tape the way the radio show was recorded. Jack told Bing that he did not see why it could not be done, and Bing put money into the Electronic Division of Bing Crosby Enterprises so that Jack could build him a recorder. Jack Mullin probably had taken on the greatest challenge of his life. He never said anything to me about not being able to do it. I believe that he and Wayne Johnson thought that it could be done. It was to be a long hard struggle.

The Bing Crosby radio show on CBS continued until the end of the 1953 season, which was on 30 May 1954. In early 1954 Bing had made the difficult decision to end the production, which meant that many lifelong relationships were to change or be severed. The first television show that involved Bing was a telethon on 21 June 1952 that he co-hosted with Bob Hope to help finance the American Olympic team. However, the first big Bing Crosby television show was produced in 1953 and aired on 3 January 1954. It was a mixture of his radio show and 35 mm movie technologies. The audio for the television program was prerecorded and edited in the same manner as his radio show was. The audio was then played back and synced with the 35 mm movie cameras.

The 1954 show was the first real introduction of Bing Crosby to the television audiences. However, he had been doing walk-ons and other television appearances on shows hosted by other people. To keep his name in front of the radio audiences, Bing prerecorded short radio shows beginning in 1954 and going into 1962. These included shows with Buddy Cole and his group and Rosemary Clooney that were syndicated and distributed to stations that wanted them. Buddy Cole used a recording technique invented by Les Paul, who also was a good friend of Bing. The record over-process is where one person would play or sing different parts. Each part then would be mixed with the earlier parts and recorded over the previous one. Bing gave Les Paul one of the Ampex 400 recorders, and Les modified it with a second playback head. This modification permitted him and his wife Mary Ford to do their famous record-over recordings. Les Paul also worked with Jack Mullin at the Electronic Division to improve the process.

The show with Buddy Cole lasted until 1958 when Bing had a video recorder to use. It was during this period that many changes came to tape recording. A lot of them were from Jack Mullin and the Electronic Division of the Bing Crosby Enterprises (BCE) operating out of a small facility in the BCE Building at 9030 Sunset Boulevard. The road to the video recorder was much more involved and slower than Bing would have liked. He always was around to encourage the project, and when Ampex decided to build their version he was supportive of them. Bing wanted a video recorder.

Bing Crosby Enterprises

When the Electronic Division of Bing Crosby Enterprises (BCE) was created by Basil Grillo in 1946, the main office was located in a small three-story building at 9028 Sunset Boulevard near the corner with Dohney Drive. It was built in 1936 by Bing as his main office. While Everett Crosby was the head, Basil Grillo always was in the background. The day-to-day operations were handled by Larry Crosby who held forth on the second floor. By 1951 the left side of the first floor was a Swedish masseuse, and on the right side was the location of the BCE Electronic Division (9030 Sunset Boulevard). In 1949 it became the sales office for Ampex and 3M products, but by the time I arrived it also was the location for the video tape development under Jack Mullin. Tommy Davis had moved to a small building next to the BCE building, and Frank Healey and his wife Hoppie, who was his secretary, were confined to the front of the sales space with the Ampex recorder display.

Since the recording companies and the radio networks had decided that the Ampex/3M approach was the answer there was not much sales work to be done, except for tracking orders. However, Tommy Davis went searching for new markets and found that the recording of instrumentation signals was ready for tape. He traveled around with an Ampex in the back of his station wagon signing up new customers. One of his other tasks was to service the recorders, and that was becoming a major job. I was asked to help him in the beginning and learned a lot about tape recorders and the recording process by having to repair them. We traveled to many of the missile, aircraft and nuclear test sites where the recorders were being used. My support to the sales group ended when they hired Robert Hopkin who took over most of the servicing.

The instrumentation of scientific tests was not as simple as the audio market. In 1949 when the Ampex 300 was introduced, paper chart recorders were mostly used to preserve the instrumentation results of these tests. These results were frozen on the paper and could not be played back. The preferred telemetry system at the time was the Inter-Range Instrumentation Group (IRIG) FM/FM system that had a 100 kHz information bandwidth. It consisted of a number of data channels that increased in information bandwidth with the upper channels having the highest bandwidths. One of the manufacturers of this equipment was Electro-Mechanical Research, Inc. (EMR).

A number of attempts were made to record this telemetry signal, but nothing was found that could record the entire 100kHz bandwidth except for the Scully record cutting lathe. This massive machine was the same one that was used to make the master record used by the recording companies and used early on by the Bing Crosby show. However, after one play the top channel was lost and after each subsequent play more channels were lost. These contained the important high frequency data that was not able to be preserved by any other method. When the Ampex 300 appeared it was viewed as a solution to the telemetry recording problem. The recorder operated at 15 ips with an upper frequency limit of at least 20 kHz. Therefore based on the existing knowledge of the time an increase in the tape speed to 60 ips using a larger capstan, a 100 kHz bandwidth might be possible. The government had separately approached Ampex to find a solution for the telemetry and other recording problems. Ampex tested the higher speed, but did not reach the expected upper frequency limit.

Based on the modifications Jack Mullin had made on the Magnetophon and the video tape work that he and Wayne Johnson had started to do, they suggested to Ampex that they try a combination of pre-emphasis of the higher frequencies on record in addition to some changes in the playback equalization. These changes worked, and a new product line emerged, the Ampex 301. Jack spent time during the early 1950s in helping the telemetry recording process in addition to the video tape work. One of the tests that sold the Ampex recorder for the telemetry market was held on board a missile range ship. It ran into heavy seas and the Scully lathes broke loose from their shock mountings. They destroyed the compartment, put dents in the bulkheads and were no longer useable. The Ampex recorders were still ready to record and captured all the telemetry data.

While the telemetry could now be recorded on tape, other problems appeared. The high frequency flutter caused by the tape path produced noise and distortions in the telemetry data. Since many of the recorders serviced by BCE were used to record telemetry data, we began to investigate a way to correct for this problem. We had already encountered these problems in our work on the video tape project for Bing Crosby. We knew that we could determine the flutter by using the 100 kHz control signal recorded on the tape. The flutter component could then be used to correct the video signal. Tests showed that this approach produced acceptable results with the telemetry; however, the flutter component had to be derived for each of the telemetry channels to be corrected. A system had to be developed using the analog techniques of that period that would compute a flutter component for each of the telemetry channels. Digital signal processing was still a number of years away, but when digital processing was introduced, EMR built the flutter correction technique into their telemetry demodulators.

The resulting system in 1952 was a rack full of vacuum tube multi-vibrator dividers that generated the flutter components from the 100 kHz signal for each of the channels. These components were then sent to the channel processors (one for each telemetry channel) to be combined with the channel signal to eliminate the flutter. However, the analog process became so complex that it was not stable, and only a few channels could be processed at the same time. We then turned our attention to finding the causes of the flutter and how correct for it at the source. This research led to the development of the tight loop drive. Flutter is due to the vibration of the tape as it passes the head. By making this segment of tape shorter, the frequency of the flutter was increased to the point it was no longer a problem. The typical segment was about 18 inches; whereas the tight loop drive had a segment of about 1 inch. The tape went past the past the capstan around the idler and then “pulled” by the same capstan. This arrangement shortened the tape path and controlled the tension of the tape. The resulting flutter was very low within the operating bandwidth. A test recorder was built by BCE and delivered to the government for tests in 1953. While BCE did not build more of these recorders, it became the standard for the telemetry recorder and was used in the BCE video recorder.

The group at BCE also supported a number of other projects for Bing and Ampex. One Saturday morning I was notified that Bing was asked by Judy Garland if he could have her show recorded that afternoon at the Biltmore Theater in Los Angeles. He agreed, and Tommy Davis and I went to the Biltmore with an Ampex 400 and microphones to record her show. It was quite an event with the musician’s union not knowing of the recording and having to give permission to record them. After a telephone call to their head in Chicago, we were allowed to record it, but the union kept the tape until the details were worked out with Judy. The recording session was uneventful except for the final number. Judy sat on the edge of the stage and sang “Somewhere over the Rainbow.” There was no place for a microphone; so I had to hold the microphone while hiding in the orchestra pit just below her. It was a special moment being between Judy and her audience when she sang that song. I felt as if I was in the middle of an electrical field.

Another event was the demonstration of the Ampex three track stereo recorder in 1952. Jack Mullin working with Bill Cara, a local Ampex dealer, built a special audio system to record and playback the three tracks of the experimental Ampex recorder. We built much of the electronics at BCE including three condenser microphones that used the Western Electric condenser element. They were perfectly matched along with the speakers, and we tested the frequency response of the system to ensure it was flat from about 10 cycles to 25,000 cycles. A number of recording sessions were held, from the steam locomotive and the squeal of brakes at the Glendale station to the Wurlitzer pipe organ in George Wright’s house. It included sessions with Lawrence Welk, the Santa Monica Symphony and other interesting features. A one hour demonstration tape was assembled and played around the Los Angeles area. It was received with great interest and caused many interesting reactions. One person told us he was sorry that we had to delay the start of the demonstration due to the airplane flying over. It was on the beginning of the tape. Others would look behind the curtain to see if we did not have an orchestra hidden there. Another person with a sound level meter told us we exceed the threshold of pain with the train brake squeal. These demonstrations went a long way to convince the recording companies to begin stereo recordings, and it also led to multi-track recorder.

The BCE Video Recorder

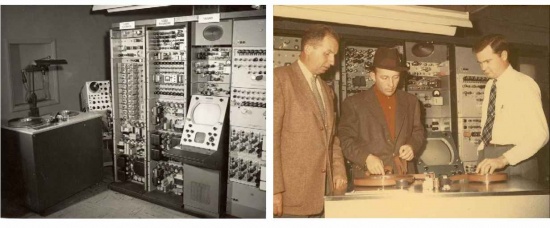

While there were many interesting experiences working at Bing Crosby Enterprises, none was as challenging as the development of a video recorder for Bing. When Jack told Bing in 1951 that it could be done, Bing responded by setting up the video recorder project to be led by Jack in the Electronic Division. Mullin reached out and recruited Wayne Johnson to assist him, and by 11 November 1951 they demonstrated the first video picture from magnetic tape. It was a video of an airplane taking off. The image was very snowy and the airplane was a dark blob, but with the commentary by Frank Healey everyone managed to see the takeoff. Frank was an ex-movie producer.

I started with BCE about a week later later and found myself involved in the construction of what I call the Mark II version. The Mark I system used the top plate from one of the portable Ampex 200 recorders modified to operate at 360 ips (20 MPH) with a modified head that gave it a bandwidth of about 1 MHz. The tape was quarter-inch, and the reels did not have any sides to reduce once-a-round effects. This lack of sides produced large piles of tape if something went wrong. At times I had to go out the front door and down Sunset Blvd. with the tape to get it back on the reel. The drive was an early version of the tight loop

The Mark II version used the same top plate as that of the Mark I, but it was modified for one inch tape. It still operated at 360 ips with the early version of the tight loop drive. Jack Mullin and Wayne Johnson had decided to build the Mark II system before the 11 November demonstration and were actively engaged in its construction. When I started at BCE they were testing various head stacks and working with William Wetzel at 3M to improve the tape quality for the recorder. It was obvious that main problem was how to increase the recorded bandwidth on the tape. We would find out over the next months that there was a lot that was not known about how the head-tape process works.

A discussion over using a rotary head approach to that of longitudinal had taken place, and there was much doubt that the rotary head would work. It also would have been difficult for the BCE group to implement it because of our lack of the mechanical facilities to build one. The longitudinal approach was selected with multiple tracks. Instead of using a rotary head, the multiple tracks were electronically scanned. The Mark II system had 12 tracks recorded on the 1 inch tape. Ten of the tracks were used for the video, and the other two, one on the top of the tape and one on the bottom, were used for audio, sync and reference signals.

The video signal in the record subsystem was sampled with the rate tied to the video sync signal. These samples or pulses were sequentially recorded across the 10 video tracks. For each set of 10 samples the polarity of the recorded pulse was reversed. This was done to prevent a bias on the tape. The result was a series of pulses recorded on each track on the tape alternating in polarity. The amplitude of the recorded pulse was equal to the amplitude of the video sample, and each channel had a 1 MHz bandwidth.

The playback system had to reverse the polarity of every other pulse and assemble them into a video stream of pulses combined with the video sync signal. The reference signals from the top and bottom tape channels were used to correct for tape speed and skew. This information was used to adjust the sampled video pulses from the tape. The video picture on the monitor consisted of a number analog “pixels” that had to be processed to eliminate the dot structure by averaging between them.

About a month after I started, Dean DeMoss and Chester Shaw were hired to help build and test the new electronics for the Mark II system. Gene Brown provided the mechanical support, and the system was built and operational by early 1952. Wayne Johnson and I were working on the system Friday night, 14 March 1952, and had completed the last adjustment to it. It was ready for its first recording test, and we decided to try it before we went home. A video program was recorded and played back; it could have been classified as a fair picture. However, it did have the “pixels” since the additional processing had not been added. We jumped up and down and cheered. It turns out that we were the only two to see the picture because Wayne came in the next day and dismantled the recorder to “improve” it. Jack Mullin found out on Monday and was not happy that he missed the first successful test recording session.

During the 1952 and 1953 period the major effort was concentrated on improving the frequency response and reducing the tape speed. Many heads designs were tested using different types of magnet materials, gap sizes and materials, and head windings. To make the heads, a precision optical lapping capability was installed along with a way of winding the coils on the assembled head segments. After trying many different head configurations, it was realized that there was a limitation in recording high frequencies on magnetic tape. A point was reached where changes in the head configuration and the tape speed made little difference in the upper frequency that could be recorded.

There were a number of other groups that were working on the video recorder. One of these was RCA, and its chairman General David Sarnoff wanted one for his birthday. By 1953 they had demonstrated a system that ran at 360 inches per second like the first BCE machine in 1951. It had better quality using video compression, but only lasted 4 minutes per reel. The same year Sarnoff of RCA and his board of directors visited BCE to see if they could buy our recorder. The party arrived in a number of black limousines. Sarnoff was in the first dressed in gray and the board in the rest, dressed in black. As Sarnoff marched up the driveway the board fell in two-by-two behind him. They went into our small laboratory for the demonstration. Sarnoff sat in the middle and the board on either side of him. After the demonstration they went upstairs to the conference room. Sarnoff told Frank Healey that he wanted to buy the recorder, and Frank told him it was not for sale. Sarnoff told Frank that he would just buy them out; to which Frank replied “You do not have enough money!” The RCA group left.

During this period the tight loop drive was perfected, and the correction of wow and flutter effects addressed. Much of this work also was used to improve the recording of the instrumentation telemetry. In the summer of 1954, I met Eugene Sakasegawa who was chief engineer of the USC television station. We were still looking for people who were good engineers with video experience, and I encouraged him to join us. He was hired, and his first assignment was to learn how to make magnetic heads. Gene was a craftsman and took up the challenge. After a couple of months of building new types of heads and not making any progress, Gene produced a head that broke the 1 MHz frequency barrier. Jack and Wayne could not believe it.

When asked what he did to make the head, he said that he made some small cuts inside the head to make it look better. He had been lapping the head halves to create a uniform gap and also the head face. These actions did make a small difference in the performance, but the “beauty treatment” was the key. The head laminations at the head gap were different widths and caused a non-uniform magnetic pattern across the tape (top to bottom). Gene had made a very accurate cut behind the head gap across the laminations. This cut made them the same thickness and caused the magnetic pattern across the tape to be uniform.

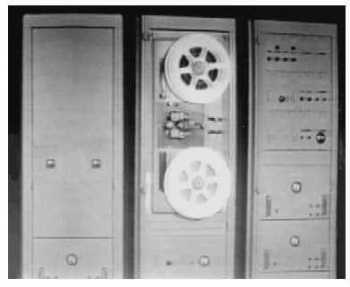

A number of different cuts were tested until proper configuration was found. The result of the head “beauty treatment” was to reduced the tape speed and produce a new design for the recording the video information. The new “Mark III” recorder operated at 100 ips with half-inch tape using longitudinal recording and no scanning. It recorded color video and sound with three heads - video, color, and sound/reference. The recorder also employed video compression techniques, and an early version was demonstrated in February 1955. The recorder was further refined and demonstrated in June 1955. Based on the performance of this new recorder CBS ordered three of them, and the summer of that year we worked building them. In late 1955 Bing asked Jack Mullin to visit Ampex to see their video tape recorder. We knew that they were working on one, but did not know how far they had come.

Jack went to Ampex near the end of the year and came back with the news that it was over, Ampex had a better recorder. Bing sent another $50,000 check to Ampex for the first of their video recorders. It was delivered to his TV station in Washington State. Ampex demonstrated their rotary head machine on 14 April 1956; CBS cancelled their order with BCE and bought the Ampex recorder. The Mark III recorders were then converted to wide band instrumentation recorders and sold.

The Wideband after Video

The year 1956 began with a new direction for the Electronics Division; the video tape work was over and the group was to be sold. The new direction for the group was established by an order from the Air Force for an airborne wideband recorder. Much of the development work done for the video recorder could be used to build a wideband longitudinal recorder; so the core of the BCE technology was not lost. The tight loop drive, high frequency heads and record and playback electronics were used for the airborne recorder. However, we had to make the unit more compact and lighter weight. The other specifications that were new to us were shock and vibration. We had to shake and drop test the top plate on which the motors and electronics were mounted. It was made of cast aluminum with mounting brackets, and during its first drop test it broke.

It was another case of having to learn a new design approach, the world of military standards. When the top plate was machined the corners of the mounting brackets were made sharp, and that we learned put a lot of stress on the point where the brackets attached to the top plate. Once rounded corners were used, the test was a success. We were not really equipped to do major mechanical operations, and that was one reason for not trying the rotary head approach. Another problem was solved by the bathroom sink and a can of Draino. Aluminum parts had to be anodized, and so this process was done in the sink with Draino. We had the cleanest drains on Sunset Boulevard. Through all of these new standards problems, the recorder took shape and was tested in late 1956. It was installed successfully in the spring of 1957.

During 1956 Bing Crosby’s brother, Everett, was tasked with finding for a buyer for the Electronics Division. While the video market was lost to Ampex, the success of the wideband recorder was the solution to the new instrumentation problems that required bandwidths beyond the traditional 100 kHz recorders. With Ampex focused on the rotary head technology that chopped some types of signals, there was an opening for wideband longitudinal recording that did not have any head switching. The 3M Company was finding that in order to keep up with the competition it had to move into the equipment market. An agreement was reached with Bing Crosby Enterprises in August 1956 to buy the Electronics Division. The transfer was made in 1957 after the Air Force contract was concluded.

When I returned to California that year from college, I found a different organization. The changeover occurred while I was traveling across the country. Jack Mullin, who was my trusted mentor, told me that I could stay, but there was much more to the world than where I had spent my last six years. I took his advice, and found myself at Sylvania EDL in Mt View, California. It was quite a change, but before long I was designing systems that had the 3M Mincom wideband recorder in them. It looked very familiar since it was based on the Bing Crosby recorder.

Jack Mullin went to 3M along with many of the Crosby group. Eugene Sakasegawa (Saki) started his magnetic head business, and the Saki magnetic head was known as one of the best. Wayne Johnson consulted with Sony in Japan on video tape recorders and became involved with the Winston tape recorder company that was started by others from BCE.

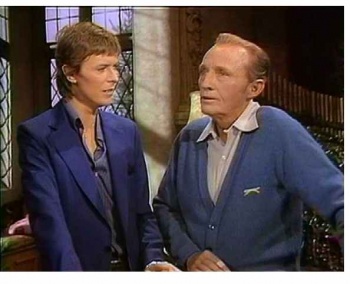

What about Bing? Well, he had his video recorder and now was doing television programs like he had done his radio shows. Many years later Bing recorded his last television program in September 1977 in London with rock star David Bowie. Since the session was recorded, these two opposites were able to put aside their nervousness when they did the duet of Little Drummer Boy. TV Guide listed the Crosby-Bowie duet as one of the 25 most memorable musical moments of 20th century television. Bing died on 14 October 1977, but it was decided to show the program. The last Christmas Show was aired on 30 November 1977.

Jack Mullin remained with 3M Mincom until his retirement. Peter Hammar, the Ampex Historian, said “He is justifiably honored as one of the greatest innovators in the history of the technology so important to broadcasting in the last half of the 20th Century: magnetic tape recording.”

Links

The following two links provide more information on Bing Crosby and his recordings: http://bingcrosby.com/bing/

http://www.bingmagazine.co.uk/ICC/InternationalClubCrosby.html

For information on the Ampex video recorder development see:

Video

<flvplayer>Littledrummerboy.flv|456|339</flvplayer>

Bing Crosby and David Bowie singing "Little Drummer Boy", aired on 30 November 1977 after Bing died. Courtesy: Bing Crosby enterprises