Milestones:Georgetown Steam Hydro Generating Plant, 1900 and Milestones:Reception of Transatlantic Radio Signals, 1901: Difference between pages

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== | == Reception of Transatlantic Radio signals, 1901 == | ||

[[Image: | [[Image:Reception transatlantic radio signals.jpg|thumb]] | ||

[[Image: | [[Image:Transatlantic Radio Milestone 1403.jpg|thumb|right]] | ||

Signal Hill, Newfoundland Dedicated October 1985 - [[IEEE Newfoundland & Labrador Section History|IEEE Newfoundland-Labrador Section]] | |||

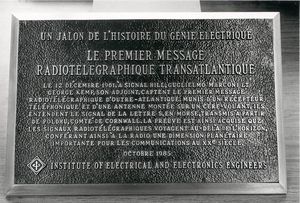

'' | ''At Signal Hill on December 12, 1901, [[Guglielmo Marconi]] and his assistant, George Kemp, confirmed the reception of the first transatlantic radio signals. With a telephone receiver and a wire antenna kept aloft by a kite, they heard Morse code for the letter "S" transmitted from Poldhu, Cornwall. Their experiments showed that radio signals extended far beyond the horizon, giving radio a new global dimension for communication in the twentieth century.'' | ||

'''The plaque can be viewed | '''The plaque can be viewed in Signal Hill National Park, St. John's, Newfoundland, Canada.''' | ||

On 12 December 1901, [[Guglielmo Marconi]] and his assistant, George Kemp, heard the faint clicks of [[Morse Code|Morse code]] for the letter "s" transmitted without wires across the Atlantic Ocean. This achievement, the first reception of transatlantic radio signals, led to considerable advances in both science and technology. It demonstrated that radio transmission was not bounded by the horizon, thus prompting [[Arthur E. Kennelly|Arthur Kennelly]] and [[Oliver Heaviside|Oliver Heaviside]] to suggest, shortly thereafter, the existence of a layer of ionized air in the upper atmosphere (the [[Kennelly-Heaviside Layer|Kennelly-Heaviside layer]], now called the ionosphere). Marconi's experiment also gave the new technology of "[[Wireless Telegraphy|wireless telegraphy]]" a global dimension that eventually made radio one of the major forms of communication in the twentieth century. | |||

In 1901, Marconi built a powerful wireless station at Poldhu, Cornwall, (corresponding IEEE Milestone) in preparation for a transatlantic test. The spark-gap transmitter fed a mammoth antenna array -- four hundred wires suspended from 20 masts, each 200 feet tall, placed in a circle. A similar station was set up on the American side of the Atlantic at South Wellfleet, Cape Cod. | |||

Then a series of disasters struck. On 17 September a ferocious gale hit the Poldhu station, destroying the elaborate antenna system. A temporary one was put in its place a week later, but tests showed that it was too inefficient to reach the Cape Cod station. Consequently, before leaving England for North America, Marconi decided to set up his equipment at St. John's, Newfoundland, which was much closer to Poldhu. The decision proved academic in any case, because on 26 November, the day before Marconi's scheduled departure, the Cape Cod antenna blew down in a hurricane. | |||

Landing at St. John's on 6 December, Marconi and his assistants set up their experimental apparatus on a table in the Signal Hill barracks near the harbor. Meanwhile, an improved antenna: had been installed at the Poldhu station, whose operators had instructions to send Morse code for the letter "s" from 3 to 7 pm (GMT) starting on 11 December. Marconi tested the winds on the 10th by sending aloft a kite trailing a wire antenna, but the kite broke loose. At the prearranged time on the 11th, Marconi and his assistants sent up a balloon, but heard nothing from their receiver. They next dispensed with the tuned receiver and tried a more sensitive detector, but the balloon broke loose. On the 12th, a strong gale still blew and carried away the first kite they sent up. The second kite, which trailed 500 feet of antenna wire, stayed up long enough for Marconi and Kemp to hear the transatlantic signals through a telephone earpiece connected to the receiver. Marconi's diary for that date has the simple entry, "Sigs. at 12:30, 1:10 and 2:20. 11 more signals were confirmed on the next day, Friday the 13th, but none on Saturday. On Monday the 16th, Marconi released the news to the press and then began packing for a new location because the Anglo-American Telegraph Company threatened legal action for violating its communication monopoly in Newfoundland. | |||

Marconi's announcement met with enthusiastic acclaim, but also with some skepticism. After all, the only witness was George Kemp, hardly an impartial observer, and the signals were too weak to operate an automatic recorder. Two months later, though, Marconi received transatlantic signals of sufficient strength from Poldhu to operate a Morse inker in the presence of witnesses. (Although later knowledge of radio-wave propagation indicates that the Signal Hill reception occurred under inopportune conditions, recent historians have suggested that Marconi picked up a high-frequency harmonic on his un-tuned receiver.) In January 1902, between the time of the Signal Hill reception and the later verification, the [[AIEE History 1884-1963|American Institute of Electrical Engineers]] held their [[Archives:AIEE Annual Dinner Program/Menu, 1902|annual dinner meeting in honor of Marconi]]. In attendance were such electrical engineering notables as [[Alexander Graham Bell]], [[Charles Proteus Steinmetz|Charles Proteus Steinmetz]], and [[Michael Pupin|Michael Pupin]]. [[Thomas Alva Edison|Thomas Edison]], who sent his regrets, called Marconi "the young man who had the monumental audacity to attempt, and succeed in, jumping an electrical wave clear across the Atlantic Ocean." | |||

== Map == | == Map == | ||

{{#display_map: | {{#display_map:47.571849, -52.689165~ ~ ~ ~ ~Signal Hill, Newfoundland, Canada|height=250|zoom=10|static=yes|center=47.571849, -52.689165}} | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Communications|Transatlantic]] [[Category:Radio communication|Transatlantic]] [[Category:News|Transatlantic]] | ||

[[Category: | |||

[[Category: | |||

Revision as of 17:54, 6 January 2015

Reception of Transatlantic Radio signals, 1901

Signal Hill, Newfoundland Dedicated October 1985 - IEEE Newfoundland-Labrador Section

At Signal Hill on December 12, 1901, Guglielmo Marconi and his assistant, George Kemp, confirmed the reception of the first transatlantic radio signals. With a telephone receiver and a wire antenna kept aloft by a kite, they heard Morse code for the letter "S" transmitted from Poldhu, Cornwall. Their experiments showed that radio signals extended far beyond the horizon, giving radio a new global dimension for communication in the twentieth century.

The plaque can be viewed in Signal Hill National Park, St. John's, Newfoundland, Canada.

On 12 December 1901, Guglielmo Marconi and his assistant, George Kemp, heard the faint clicks of Morse code for the letter "s" transmitted without wires across the Atlantic Ocean. This achievement, the first reception of transatlantic radio signals, led to considerable advances in both science and technology. It demonstrated that radio transmission was not bounded by the horizon, thus prompting Arthur Kennelly and Oliver Heaviside to suggest, shortly thereafter, the existence of a layer of ionized air in the upper atmosphere (the Kennelly-Heaviside layer, now called the ionosphere). Marconi's experiment also gave the new technology of "wireless telegraphy" a global dimension that eventually made radio one of the major forms of communication in the twentieth century.

In 1901, Marconi built a powerful wireless station at Poldhu, Cornwall, (corresponding IEEE Milestone) in preparation for a transatlantic test. The spark-gap transmitter fed a mammoth antenna array -- four hundred wires suspended from 20 masts, each 200 feet tall, placed in a circle. A similar station was set up on the American side of the Atlantic at South Wellfleet, Cape Cod.

Then a series of disasters struck. On 17 September a ferocious gale hit the Poldhu station, destroying the elaborate antenna system. A temporary one was put in its place a week later, but tests showed that it was too inefficient to reach the Cape Cod station. Consequently, before leaving England for North America, Marconi decided to set up his equipment at St. John's, Newfoundland, which was much closer to Poldhu. The decision proved academic in any case, because on 26 November, the day before Marconi's scheduled departure, the Cape Cod antenna blew down in a hurricane.

Landing at St. John's on 6 December, Marconi and his assistants set up their experimental apparatus on a table in the Signal Hill barracks near the harbor. Meanwhile, an improved antenna: had been installed at the Poldhu station, whose operators had instructions to send Morse code for the letter "s" from 3 to 7 pm (GMT) starting on 11 December. Marconi tested the winds on the 10th by sending aloft a kite trailing a wire antenna, but the kite broke loose. At the prearranged time on the 11th, Marconi and his assistants sent up a balloon, but heard nothing from their receiver. They next dispensed with the tuned receiver and tried a more sensitive detector, but the balloon broke loose. On the 12th, a strong gale still blew and carried away the first kite they sent up. The second kite, which trailed 500 feet of antenna wire, stayed up long enough for Marconi and Kemp to hear the transatlantic signals through a telephone earpiece connected to the receiver. Marconi's diary for that date has the simple entry, "Sigs. at 12:30, 1:10 and 2:20. 11 more signals were confirmed on the next day, Friday the 13th, but none on Saturday. On Monday the 16th, Marconi released the news to the press and then began packing for a new location because the Anglo-American Telegraph Company threatened legal action for violating its communication monopoly in Newfoundland.

Marconi's announcement met with enthusiastic acclaim, but also with some skepticism. After all, the only witness was George Kemp, hardly an impartial observer, and the signals were too weak to operate an automatic recorder. Two months later, though, Marconi received transatlantic signals of sufficient strength from Poldhu to operate a Morse inker in the presence of witnesses. (Although later knowledge of radio-wave propagation indicates that the Signal Hill reception occurred under inopportune conditions, recent historians have suggested that Marconi picked up a high-frequency harmonic on his un-tuned receiver.) In January 1902, between the time of the Signal Hill reception and the later verification, the American Institute of Electrical Engineers held their annual dinner meeting in honor of Marconi. In attendance were such electrical engineering notables as Alexander Graham Bell, Charles Proteus Steinmetz, and Michael Pupin. Thomas Edison, who sent his regrets, called Marconi "the young man who had the monumental audacity to attempt, and succeed in, jumping an electrical wave clear across the Atlantic Ocean."