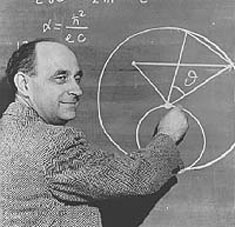

Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi

Born: 29 September 1901

Died: 28 November 1954

Under the west stand of the University of Chicago’s squash courts in Stagg Field, sits a plaque. It reads: “On December 2, 1942, man achieved here the first self-sustaining chain reaction and thereby initiated the controlled release of nuclear energy.” How did the squash courts at the University of Chicago became the site of the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction? The story begins in Italy in 1915.

In Rome that year a 14 year old boy, grieving the death of his older brother, sought distraction in books. Roaming the Campo de Fiori he happened upon two antique volumes of elementary physics. Our world was never to be the same. The boy was Enrico Fermi, and he would become the man who in 1942 performed the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction at the University of Chicago’s squash courts.

Fermi’s interest in physics was intense. At 19, he entered the University of Pisa, where, by some accounts, he shortly began instructing his teachers. At the tender age of 25, he became a professor of theoretical physics at the University of Rome. In 1934, Fermi almost discovered nuclear fission—the process that was used in the first atomic bomb—while conducting experiments in the radioactive transformations that resulted when various elements were repeatedly bombarded with neutrons. However, Fermi missed this opportunity because the sheet of foil he used to cover his uranium sample, which would have created fission, was too thick. It blocked the fission fragments from being recorded and went unnoticed. Though Fermi failed to discover fission, he did discover that passing neutrons through a light-element “moderator,” such as paraffin, slowed them down and in turn, increased their effectiveness. This discovery was instrumental in generating the heat needed by a nuclear reactor to generate electricity. In 1938 Fermi was awarded the Nobel Prize for his work.

Fermi traveled from Italy to Sweden to obtain his Nobel medal and never returned home. Italy’s fascist and anti-Semitic climate increasingly disturbed him. Like many European scientists of the period he left Europe and settled in the United States, taking employment at the University of Chicago. Others at the university were working on the atomic bomb. Fermi’s task was to find a way to control the chain reaction that resulted from fission. His answer was to create a nuclear reactor, which Fermi, whose English was still poor, called simply a “pile,” so that, theoretically, he could insert a neutron-absorbing material into the midst of the fission process to control its speed.

In December 1942 Fermi and his team were prepared to test their reactor. Due to space considerations, the “pile” was set up in the university’s squash court. The test did not occur without some concern. Up to that very moment Fermi’s notions about controlling fission were based entirely on theory, not practice. If he was wrong, Chicago could be blown away. The test began. At first, just a couple of rods were removed. Gradually, Fermi pulled more. Finally, it was apparent—Fermi and his team had created a self-sustaining nuclear reaction—the first controlled flow of energy from a source other than the sun. A coded message told the government of this success: “The Italian navigator has just landed in the new world.”