Electric Meter: Difference between revisions

m (Text replace - "[[Category:Computers and information processing" to "[[Category:Computing and electronics") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

On 14 August 1888 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Oliver B. Shallenberger received a patent for the watt-hour meter, a device that measured the amount of AC current and made possible the business model of the electric utility. | On 14 August 1888 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Oliver B. Shallenberger received a patent for the watt-hour meter, a device that measured the amount of AC current and made possible the business model of the electric utility. | ||

Shallenberger was a former naval officer hired by the [[Westinghouse_Electric_Corporation|Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co.]] By 1888, he rose to the power of its chief electrician. Westinghouse was fighting the “[[AC_vs._DC|War of the Currents]]” in the 1880s against [[Thomas_Alva_Edison|Thomas Edison]]. Westinghouse, which had purchased the rights to [[Nikola_Tesla|Nikola Tesla’s]] polyphase system, was trying to expand the reach of [[Milestones:Alternating_Current_Electrification,_1886 alternating current]] (AC) in American homes. Edison’s system of direct current (DC) was the American standard at the time, but it was less practical for residential use. | Shallenberger was a former naval officer hired by the [[Westinghouse_Electric_Corporation|Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co.]] By 1888, he rose to the power of its chief electrician. Westinghouse was fighting the “[[AC_vs._DC|War of the Currents]]” in the 1880s against [[Thomas_Alva_Edison|Thomas Edison]]. Westinghouse, which had purchased the rights to [[Nikola_Tesla|Nikola Tesla’s]] polyphase system, was trying to expand the reach of [[Milestones:Alternating_Current_Electrification,_1886|alternating current]] (AC) in American homes. Edison’s system of direct current (DC) was the American standard at the time, but it was less practical for residential use. | ||

For example, Edison failed to develop a simple means of measuring how much power a consumer had used. Initially, he charged per lamp, but soon switched to a chemical method to measure amperes per hour. He installed an jar containing two zinc plates submerged in a zinc-sulfate electrolyte. As electricity flowed through the jar, it dissolved zinc off the positive plate and onto the negative one. Each month, workers checked to see how much zinc had moved. Edison actually preferred this messy and time-consuming process to a mechanical method, but its accuracy was questionable. | For example, Edison failed to develop a simple means of measuring how much power a consumer had used. Initially, he charged per lamp, but soon switched to a chemical method to measure amperes per hour. He installed an jar containing two zinc plates submerged in a zinc-sulfate electrolyte. As electricity flowed through the jar, it dissolved zinc off the positive plate and onto the negative one. Each month, workers checked to see how much zinc had moved. Edison actually preferred this messy and time-consuming process to a mechanical method, but its accuracy was questionable. | ||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

Hundreds of thousands of these meters were built in the coming decades, allowing AC power to take off as an everyday consumer technology. Shallenberger’s basic design remains in use today. Because these meters operated on electrical current’s induced magnetic field, they consumed virtually no power. Consumers could feel more confident that they were only being charged for the power they used, and could more accurately monitor their consumption. | Hundreds of thousands of these meters were built in the coming decades, allowing AC power to take off as an everyday consumer technology. Shallenberger’s basic design remains in use today. Because these meters operated on electrical current’s induced magnetic field, they consumed virtually no power. Consumers could feel more confident that they were only being charged for the power they used, and could more accurately monitor their consumption. | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Computing_and_electronics]] | ||

[[Category:Measurement]] | [[Category:Measurement]] | ||

[[Category:Electric_variables_measurement]] | [[Category:Electric_variables_measurement]] | ||

[[Category:Materials]] | |||

[[Category:Metals]] | |||

[[Category:Zinc]] | |||

Revision as of 15:39, 18 September 2014

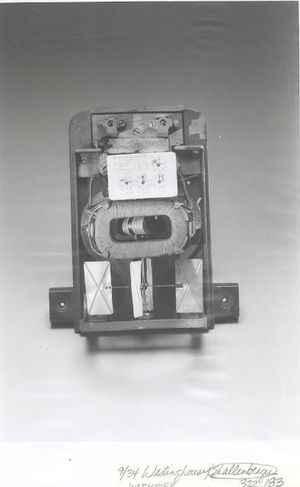

On 14 August 1888 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Oliver B. Shallenberger received a patent for the watt-hour meter, a device that measured the amount of AC current and made possible the business model of the electric utility.

Shallenberger was a former naval officer hired by the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co. By 1888, he rose to the power of its chief electrician. Westinghouse was fighting the “War of the Currents” in the 1880s against Thomas Edison. Westinghouse, which had purchased the rights to Nikola Tesla’s polyphase system, was trying to expand the reach of alternating current (AC) in American homes. Edison’s system of direct current (DC) was the American standard at the time, but it was less practical for residential use.

For example, Edison failed to develop a simple means of measuring how much power a consumer had used. Initially, he charged per lamp, but soon switched to a chemical method to measure amperes per hour. He installed an jar containing two zinc plates submerged in a zinc-sulfate electrolyte. As electricity flowed through the jar, it dissolved zinc off the positive plate and onto the negative one. Each month, workers checked to see how much zinc had moved. Edison actually preferred this messy and time-consuming process to a mechanical method, but its accuracy was questionable.

Working on applications for AC power, Shallenberger stumbled onto a solution for the problem of metering. As he was tinkering with a lamp in 1888, a spring fell out and fell on a ledge inside the lamp. He saw that the spring had rotated. Testing a hunch, he discovered that the lamp’s spinning electromagnetic fields had caused the spring to turn. Within a few weeks, Shallenberger designed a wheel that turned in relation to this rotational force, offering a means of measuring amperes per hour on an alternating current circuit.

Hundreds of thousands of these meters were built in the coming decades, allowing AC power to take off as an everyday consumer technology. Shallenberger’s basic design remains in use today. Because these meters operated on electrical current’s induced magnetic field, they consumed virtually no power. Consumers could feel more confident that they were only being charged for the power they used, and could more accurately monitor their consumption.