Early Light Bulbs: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Image:Edison Light Bulb Patent 2154.jpg|thumb|right]] | [[Image:Edison Light Bulb Patent 2154.jpg|thumb|right]] | ||

The warm glow of the light bulb is the part of today’s [[Electric Lighting|electric lighting system]] that we know best. [[Thomas Alva Edison|Thomas Edison is]] often said to have [[Edison's Incandescent Lamp|invented the light bulb]], but his bulb was not a completely original idea. In fact, the principle of electric incandescent lighting (making a wire glow by sending electricity through) had been around since at least 1802, when Englishman Humphry Davy demonstrated it. In 1840 another English inventor, Warren De la Rue, used a platinum filament inside a glass bulb, an idea Edison would later try but reject. The air inside the De la Rue bulb was pumped out, because inventors understood that if the filament was not in a vacuum, the oxygen in the air would cause a chemical reaction with the filament and destroy it. One problem with doing things this way, however, was that it was difficult to seal the glass around the wires that supply electricity to the filament. Finding a good material for the filament and keeping the air out were major problems Edison eventually overcame. | The warm glow of the light bulb is the part of today’s [[Electric Lighting|electric lighting system]] that we know best. [[Thomas Alva Edison|Thomas Edison is]] often said to have [[Edison's Incandescent Lamp|invented the light bulb]], but his bulb was not a completely original idea. In fact, the principle of electric incandescent lighting (making a wire glow by sending electricity through) had been around since at least 1802, when Englishman [[Sir Humphry Davy|Humphry Davy]] demonstrated it. In 1840 another English inventor, Warren De la Rue, used a platinum filament inside a glass bulb, an idea Edison would later try but reject. The air inside the De la Rue bulb was pumped out, because inventors understood that if the filament was not in a vacuum, the oxygen in the air would cause a chemical reaction with the filament and destroy it. One problem with doing things this way, however, was that it was difficult to seal the glass around the wires that supply electricity to the filament. Finding a good material for the filament and keeping the air out were major problems Edison eventually overcame. | ||

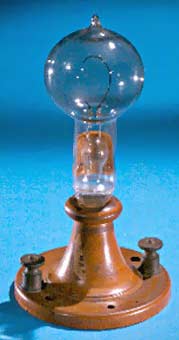

[[Image: | [[Image:EdisonLight.jpg|thumb|right|A lamp used at the historic 1879 New Year’s Eve demonstration of the Edison Lighting System in Menlo Park, New Jersey. Courtesy: The Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village.]] | ||

De la Rue’s platinum bulb worked, but platinum was far too expensive to use in commercial light bulbs. Thomas Edison, after investigating many different filament materials, settled on carbon filament in 1879. At about the same time, an English inventor named Joseph Swan came up with almost the same idea, leading to claims that it was he who really invented the light bulb. Clearly, no single inventor deserves sole credit for the light bulb. What was unique about Edison’s work was that he carried the idea from laboratory to commercialization, taking into consideration not only technical problems, but also issues like economics and the production of bulbs. | De la Rue’s platinum bulb worked, but platinum was far too expensive to use in commercial light bulbs. Thomas Edison, after investigating many different filament materials, settled on carbon filament in 1879. At about the same time, an English inventor named Joseph Swan came up with almost the same idea, leading to claims that it was he who really invented the light bulb. Clearly, no single inventor deserves sole credit for the light bulb. What was unique about Edison’s work was that he carried the idea from laboratory to commercialization, taking into consideration not only technical problems, but also issues like economics and the production of bulbs. | ||

Edison’s carbon filament gave his lighting system an inexpensive bulb, and also the carbon filament worked well at about 110 volts | Edison had begun his work on a system of electrical illumination as early as 1878. The effort Edison mounted was one he hoped could compete with gas and oil based lighting. Edison started by tackling the problem of creating a long lasting incandescent lamp, that could be used primarily for indoor use - bulbs that have glowing filaments that could burn inside of a vacuum. | ||

Carbon-arc lamps were already commercially available, especially in France and through-out Europe - but basically were used in outdoor street lighting and required on going maintenance that necessitated usually manual labor employed rather frequently in the course of a day, for the reloading of the carbon rods that were fed by intricate clock driven mechanisms when the lamps were activated and producing light. Arc lamps also did not require operation within a vacuum, as with that of incandescent lamps. Although, arc lamps usually did utilize a protective glass globe for radiating the light evenly. | |||

Many earlier inventors had previously devised incandescent lamps of sorts, such as Alessandro Volta, who demonstrated a simple stand alone glowing wire in 1800, the same year he perfected his voltaic pile or battery. Two early attempts at modest forms of incandescent lighting by inventors Henry Woodward and Mathew Evans followed this. Still others sought to develop more advanced forms of incandescent lighting but most proved to be commercially highly impractical. These attempts included electric lamps devised by Humphry Davy, James Bowman Lindsay, Heinrich Göbel, William E. Sawyer, Joseph Swan and Moses G. Farmer. Some of these early bulbs were flawed in that they had an extremely short life span, were overtly expensive to produce, and maintained high electric current load draw level. All of these factors contributed to making these inventors' or manufacturers' bulbs difficult to apply on a large scale commercially. | |||

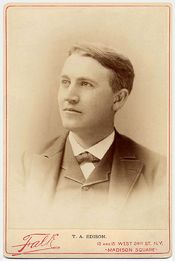

[[Image:EDISONfalkC1883rwLIPACKownerA.jpg|thumb|right|175px|'''Photo credit: Richard Warren Lipack / Wikimedia Commons.''' Original albumen cabinet card photograph of esteemed inventor Thomas A. Edison by Benjamin J. Falk, New York. Circa 1883.]]Thomas A. Edison quickly came to realize that he had to keep the thickness of the copper wire needed to connect a series of electric lights to an economically manageable size and to do so he needed to develop a lamp that would draw a relatively low amount of current. This meant that the lamp would have to have a high resistance and run at a low voltage. Edison concluded that a lamp rated at 110 volts would be most effective. | |||

Edison conducted an extensive battery of experiments and tests. Edison had sent agents around the world looking for different forms of materials that these agents would send or bring back to Edison's Menlo Park laboratory for him to test. After many experiments, most of them failed tests, Edison settled on that of a carbon filament. Edison did produce a number of experimental platinum filament lamps, but one of the draw backs with platinum lamps was that they proved too costly to produce. Other metal filaments tried as well had their various problem. Ironically Edison's first filament tests started with the carbon filament. | |||

[[File:1880EDISON1881LampsSOCKETSrwLIPACKowner.jpg|thumb|right|(400px)|'''Photo credit: Richard Warren Lipack / Wikimedia Commons.''' The evolution of Edison's incandescent electric light bulb and socket - 1880-1881. Left to right: First form "1880 Wire Terminal Base" socket and bulb as used on the S.S. Columbia - first commercial installation of Edison electric lighting system; Second form "1880 Wire Terminal Base" socket and bulb; "1880 Original Screw Base" socket and bulb and the "1881 Improved Screw Base" socket and light bulb.]] | |||

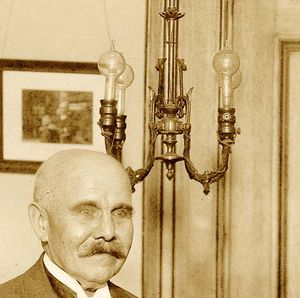

[[File:1880EDISONChandelierFrancisJehlrwLIPACKowner.jpg|thumb|right|(400px)|'''Photo credit: Richard Warren Lipack / Wikimedia Commons.''' Detail of original Edison chandelier with first form "1880 Wire Terminal Base" sockets and incandescent lamps behind "Edison Pioneer" and 'Edisonian' author Francis Jehl.]] | |||

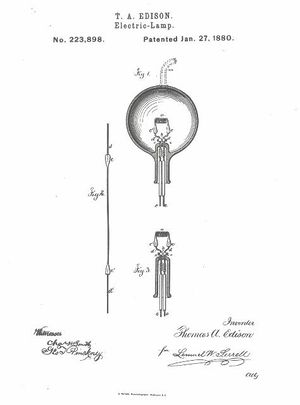

The first successful test of the carbonized cotton filament was on October 22, 1879, which lasted 13.5 hours. Edison continued to improve this design and by November 4, 1879, filed for a U.S. patent for an electric lamp using "a carbon filament or strip coiled and connected to platina contact wires." On January 27, 1880 U.S. patent number 223,898 was granted to Edison for what would become the first perfected commercially viable incandescent lamp. | |||

Although the patent described several ways of creating the carbon filament, one of which included the use of "cotton and linen thread, wood splints, papers coiled in various ways", it would not be several months after Edison's first incandescent lamp patent was granted on January 27, 1880, that he and his team discovered a carbonized bamboo filament that could last as much as 1,200 hours. The idea of using Japanese bamboo originated from Edison's recalling his examination of a few stray threads from a bamboo fishing pole he had used while relaxing on the shore of Battle Lake, Wyoming Territory, where he and other members of a scientific team had traveled to observe a total eclipse of the sun on July 29, 1878, from the Continental Divide. It was here actually that Edison devised his tasimeter, an apparatus to measure infrared radiation. | |||

Edison, in 1878, had already formed the Edison Electric Light Company in New York City with several financiers, including J. P. Morgan and the members of the Vanderbilt family. Thus, Edison had substantial financial backing as soon as he could produce a perfected commercially viable lamp. | |||

Inventor Thomas A. Edison made the first public demonstration of his perfected incandescent light bulb on December 31, 1879, in Menlo Park. It was during this time that he said: "We will make electricity so cheap that only the rich will burn candles." Edison had waited just over a month from the day of October 22, 1879 to publicly announce his invention of the incandescent lamp, because he quietly wanted to file his patent application for the light bulb before announcing the discovery to the world. A good many inventors were working to perfect the incandescent lamp and other inventions at that time, thus the prolific Edison himself especially had to be extremely careful from being preempted by some other inventor. | |||

Edison’s carbon filament gave his lighting system an commercially inexpensive bulb, and also the carbon filament worked well at about 110 volts as he had believed it would - and which Edison considered an economical and safe voltage for the distribution of electricity. In the original Edison and Swan bulbs, the filament was made by burning a cotton thread until all that was left was black carbon. However, the resulting filament was fragile, so Edison later substituted a burned 'carbonized' bamboo filament. The idea that had been tried earlier, produced far more effective results the second time around when the use of an improved vacuum pump to clear more air out of the bulbs, was employed. This gave Edison's lamps the approximately 1,200 hours extended lifetime, versus only 14 or so for the cotton filament bulb used in his first successful Menlo Park, New Jersey test that ended on October 22, 1879. | |||

[[Category: | [[Category:Energy|Light bulbs]] [[Category:Lasers, lighting & electrooptics|Light bulbs]] [[Category:Lasers, lighting & electrooptics|Light bulbs]] [[Category:Electric lighting|Light bulbs]] [[Category:News|Light bulbs]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:47, 14 September 2015

The warm glow of the light bulb is the part of today’s electric lighting system that we know best. Thomas Edison is often said to have invented the light bulb, but his bulb was not a completely original idea. In fact, the principle of electric incandescent lighting (making a wire glow by sending electricity through) had been around since at least 1802, when Englishman Humphry Davy demonstrated it. In 1840 another English inventor, Warren De la Rue, used a platinum filament inside a glass bulb, an idea Edison would later try but reject. The air inside the De la Rue bulb was pumped out, because inventors understood that if the filament was not in a vacuum, the oxygen in the air would cause a chemical reaction with the filament and destroy it. One problem with doing things this way, however, was that it was difficult to seal the glass around the wires that supply electricity to the filament. Finding a good material for the filament and keeping the air out were major problems Edison eventually overcame.

De la Rue’s platinum bulb worked, but platinum was far too expensive to use in commercial light bulbs. Thomas Edison, after investigating many different filament materials, settled on carbon filament in 1879. At about the same time, an English inventor named Joseph Swan came up with almost the same idea, leading to claims that it was he who really invented the light bulb. Clearly, no single inventor deserves sole credit for the light bulb. What was unique about Edison’s work was that he carried the idea from laboratory to commercialization, taking into consideration not only technical problems, but also issues like economics and the production of bulbs.

Edison had begun his work on a system of electrical illumination as early as 1878. The effort Edison mounted was one he hoped could compete with gas and oil based lighting. Edison started by tackling the problem of creating a long lasting incandescent lamp, that could be used primarily for indoor use - bulbs that have glowing filaments that could burn inside of a vacuum.

Carbon-arc lamps were already commercially available, especially in France and through-out Europe - but basically were used in outdoor street lighting and required on going maintenance that necessitated usually manual labor employed rather frequently in the course of a day, for the reloading of the carbon rods that were fed by intricate clock driven mechanisms when the lamps were activated and producing light. Arc lamps also did not require operation within a vacuum, as with that of incandescent lamps. Although, arc lamps usually did utilize a protective glass globe for radiating the light evenly.

Many earlier inventors had previously devised incandescent lamps of sorts, such as Alessandro Volta, who demonstrated a simple stand alone glowing wire in 1800, the same year he perfected his voltaic pile or battery. Two early attempts at modest forms of incandescent lighting by inventors Henry Woodward and Mathew Evans followed this. Still others sought to develop more advanced forms of incandescent lighting but most proved to be commercially highly impractical. These attempts included electric lamps devised by Humphry Davy, James Bowman Lindsay, Heinrich Göbel, William E. Sawyer, Joseph Swan and Moses G. Farmer. Some of these early bulbs were flawed in that they had an extremely short life span, were overtly expensive to produce, and maintained high electric current load draw level. All of these factors contributed to making these inventors' or manufacturers' bulbs difficult to apply on a large scale commercially.

Thomas A. Edison quickly came to realize that he had to keep the thickness of the copper wire needed to connect a series of electric lights to an economically manageable size and to do so he needed to develop a lamp that would draw a relatively low amount of current. This meant that the lamp would have to have a high resistance and run at a low voltage. Edison concluded that a lamp rated at 110 volts would be most effective.

Edison conducted an extensive battery of experiments and tests. Edison had sent agents around the world looking for different forms of materials that these agents would send or bring back to Edison's Menlo Park laboratory for him to test. After many experiments, most of them failed tests, Edison settled on that of a carbon filament. Edison did produce a number of experimental platinum filament lamps, but one of the draw backs with platinum lamps was that they proved too costly to produce. Other metal filaments tried as well had their various problem. Ironically Edison's first filament tests started with the carbon filament.

The first successful test of the carbonized cotton filament was on October 22, 1879, which lasted 13.5 hours. Edison continued to improve this design and by November 4, 1879, filed for a U.S. patent for an electric lamp using "a carbon filament or strip coiled and connected to platina contact wires." On January 27, 1880 U.S. patent number 223,898 was granted to Edison for what would become the first perfected commercially viable incandescent lamp.

Although the patent described several ways of creating the carbon filament, one of which included the use of "cotton and linen thread, wood splints, papers coiled in various ways", it would not be several months after Edison's first incandescent lamp patent was granted on January 27, 1880, that he and his team discovered a carbonized bamboo filament that could last as much as 1,200 hours. The idea of using Japanese bamboo originated from Edison's recalling his examination of a few stray threads from a bamboo fishing pole he had used while relaxing on the shore of Battle Lake, Wyoming Territory, where he and other members of a scientific team had traveled to observe a total eclipse of the sun on July 29, 1878, from the Continental Divide. It was here actually that Edison devised his tasimeter, an apparatus to measure infrared radiation.

Edison, in 1878, had already formed the Edison Electric Light Company in New York City with several financiers, including J. P. Morgan and the members of the Vanderbilt family. Thus, Edison had substantial financial backing as soon as he could produce a perfected commercially viable lamp.

Inventor Thomas A. Edison made the first public demonstration of his perfected incandescent light bulb on December 31, 1879, in Menlo Park. It was during this time that he said: "We will make electricity so cheap that only the rich will burn candles." Edison had waited just over a month from the day of October 22, 1879 to publicly announce his invention of the incandescent lamp, because he quietly wanted to file his patent application for the light bulb before announcing the discovery to the world. A good many inventors were working to perfect the incandescent lamp and other inventions at that time, thus the prolific Edison himself especially had to be extremely careful from being preempted by some other inventor.

Edison’s carbon filament gave his lighting system an commercially inexpensive bulb, and also the carbon filament worked well at about 110 volts as he had believed it would - and which Edison considered an economical and safe voltage for the distribution of electricity. In the original Edison and Swan bulbs, the filament was made by burning a cotton thread until all that was left was black carbon. However, the resulting filament was fragile, so Edison later substituted a burned 'carbonized' bamboo filament. The idea that had been tried earlier, produced far more effective results the second time around when the use of an improved vacuum pump to clear more air out of the bulbs, was employed. This gave Edison's lamps the approximately 1,200 hours extended lifetime, versus only 14 or so for the cotton filament bulb used in his first successful Menlo Park, New Jersey test that ended on October 22, 1879.