Oral-History:Lewis Terman

About Lewis Terman

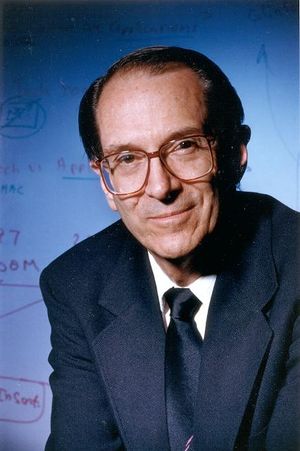

Lewis (Lew) M. Terman, is an IEEE Life Fellow and served as IEEE president in 2008. He joined the IRE (one of IEEE’s predecessor societies) in 1958 as a student. In an interview with the IEEE Foundation, he recalled, “Once could say that the IRE/IEEE was in my blood” because he is the son of Frederick Terman, another prominent IEEE member and IRE President in 1941, and Sibyl Walcutt Terman, an expert in the teaching of reading. He was named after his grandfather, a psychologist who developed the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Quotient. Raised in California and received his B.S. in Physics and his M.S. and Ph.D. in electrical engineering from Stanford in 1956, 1958, and 1961, respectively. He worked for IBM for forty-five years, retiring from the company’s research division in 2006. His research interests included solid-state circuits, semiconductor technology, and memory design and technology among other topics.

Terman and his wife, Bobbie, are members of the IEEE Foundation’s Heritage Circle, which acknowledges the individuals who have “given back” to IEEE throughout their lifetime. They have donated to IEEE humanitarian projects, including IEEE Smart Village.

About the Interview

LEWIS TERMAN: An Interview Conducted by Sheldon Hochheiser, IEEE History Center, 9 March 2011

Interview #548 for the IEEE History Center, The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.

Copyright Statement

This manuscript is being made available for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the IEEE History Center. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of IEEE History Center.

Request for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the IEEE History Center Oral History Program, IEEE History Center, 445 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08854 USA or ieee-history@ieee.org. It should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

Lewis Terman, an oral history conducted in 2011 by Sheldon Hochheiser, IEEE History Center, Piscataway, NJ, USA.

Interview

INTERVIEW WITH: Lewis Terman

INTERVIEWER: Sheldon Hochheiser

DATE: 9 March 2011

PLACE: Piscataway, New Jersey

Early life and education

Hochheiser:

This is Sheldon Hochheiser of the IEEE History Center. It's the 9th of March 2011. I'm here at the IEEE Operation Center in Piscataway, New Jersey with IEEE Past President and retired IBM Researcher Lew Terman. Good afternoon.

Terman:

Good afternoon. Glad to be here.

Hochheiser:

By way of introduction, I have read the extensive interviews you did last year with the Computer History Museum on your career and your recollections of your father Frederick Terman's career. What I want to do is not duplicate what you have already done but complement it by focusing on your activities as an IEEE member, volunteer, and leader.

Terman:

Thank you.

Hochheiser:

I still would like a little bit of background. Where were you born and raised?

Terman:

I was born in San Francisco, [California], but raised on the Stanford [University] campus. My father was a professor, of course, at Stanford.

I was born in 1935, and except for three years during the Second World War when he was running a laboratory outside of Boston, we were on the Stanford campus. I attended Stanford, both undergraduate and graduate, and after that started to work for IBM at the Research Center in Yorktown Heights, New York. We've been there ever since.

Hochheiser:

What did your mother do?

Terman:

She was a graduate student when she met my father. In those days, women did not generally pursue a career once married. She was actually a very intelligent woman and had done a lot of work on teaching children to read. She was one of the early proponents of phonics to teach reading. On the Stanford campus there were a lot of children who were very bright, but apparently from what she said a number of them had problems learning to read with the current education system. She had this program she worked out to teach children to read. My brothers and I were reading by the age of five or so. I skipped first grade and I think that [my brothers] all skipped a grade because we knew how to read before we actually went to school.

She also wrote a book. Rudolph Flesch had written a book that was rather famous at the time, in the early 1950s, Why Johnny Can't Read. The title of my mother's book was Reading: Chaos and Cure. She wrote the book with her brother, Charles Child Walcutt, who was a distinguished professor at Queens College in New York City. She made the mistake of the book going through the same publisher that published my father's books, McGraw-Hill. McGraw-Hill had a very big business in textbooks that went to the schools on reading, so they didn't really push it very much. There were reasonable sales of 5,000 or something, I think. It was a big thing at that time because there was a big problem with people learning to read. She did that and she did it quite well, and she had a real impact. She had something that she did quite well and had a local impact.

Hochheiser:

Were you interested in science and technology when you were growing up?

Terman:

Yes. A lot of people who were interested in science diddled. They made radio sets. They did this and that. I was more interested in things like, I flew model airplanes on the Stanford campus before they started leasing all the land in the Stanford Industrial Park, which was kind funny because you were doing something, and you built something, and you had to make them fly right and so forth. But I didn't do ham radio or that sort of thing.

I took a course from a person whose name will come up shortly, I assume, Mr. Martin, who was also a high school physics teacher, and he was on radio. He taught us how radios worked. We took radios from home and went through and worked out the circuit and so forth. Instead of creating my own radio or that sort of thing, I went in and read the books on how radios work. I was more of a theoretician than that, which is kind of interesting. I built my own hi-fi amplifier Heathkit and also the voltmeter that they had. So, I was interested in it.

Looking back and thinking about it before this interview, I never saw my father in the laboratory. My father had a lot of impact, but he had a schedule of coming home at night at 5 o'clock or 5:30, doing a little work before dinner – we sat down as a group for dinner – and then around 7 o'clock when dinner was over, he would rest for about half an hour and then he would work on writing the book. He was totally approachable. I could go in there and interrupt him and ask questions. And on the weekend, he wasn't writing a book wall-to-wall.

I was interested in technical things in high school and high school courses in science and then into physics. Very clearly that was where my interests lay. It was not that I wanted to go out and do strange and wonderful things and create stuff. I don't know. It was sort of a mixed bag. Definitely, I was interested in high school. I did well in high school on that and then I went to Stanford.

Stanford

Hochheiser:

Did you consider any other colleges besides Stanford?

Terman:

No. It was there. There seemed to be no reason to consider other colleges. One thing that was interesting: in ninth grade I sold ice cream, concessions, walking around the Stanford Stadium. That was a source of income. I got to know the sports teams and even became aware of strange sports like water polo and rugby that most people didn't know about, and it was home. I knew a lot of people from Palo Alto High School who literally went across the road to Stanford. It was the natural thing to do and there just didn't seem to be any reason to go into any other school. At that time there was no school that was better than Stanford. Okay, so I'm prejudiced.

Hochheiser:

As well you should be.

Terman:

Right.

Hochheiser:

Did you enter Stanford planning to major in physics?

Terman:

Yes. We’ll go back to Mr. Martin. In eleventh grade I had a really good chemistry teacher. Boy, it was fun to make things bubble and stuff happen, so I was going to be a chemist. In twelfth grade you take physics. Mr. Martin was a crusty individual, a well-known character in the school, but he was also a very good physics teacher with some sense of humor. A good guy overall. I through that and I said, "Oh, this is much more interesting than chemistry. In chemistry things change color and so forth. So what? Here you get into understanding what's happening in the world."

They didn't teach physics in high school at that time. They taught physics principles which were really engineering principles. So, you go through what he teaches, and it was really a good background for engineering rather than physics. I got into Stanford, and in my freshman course I didn't learn anything more than I already learned from Mr. Martin. Then they got into the more theoretical physics and all of a sudden, it was going off to where I wasn't particularly interested. I had an advisor, Robert Hofstadter – who eventually got a Nobel Prize. He said, "Go over and take the 150 series at the EE Department," which was the introductory circuits course. I took that and it was great fun. Went back and said, "That's good. This is better than what's going on in the physics department." I basically became an EE major after that – although I graduated in physics, because the EE courses that I was taking applied to the physics. Stanford was pretty good on that, in flexibility.

Hochheiser:

Did being Frederick Terman's son on the Stanford campus cause either opportunities or problems that perhaps your fellow students didn't have?

Terman:

Not that much. By the time I was going through there, he was Dean of Engineering and then by the time I had done this switchover to EE [electrical engineering] he was Provost. I didn't take his course. That was the 160 course. That was just as well. I do remember I was known around there. You had to take two years of gym and I wanted to get into the basketball course. And there was the basketball coach I knew. The guy who was signing people up for the courses said, "I'm sorry, the course is filled." I said, "Oh gee, that's too bad." The basketball coach said, "Oh, I know him. Let him in." That was positive. Negative? People looking at me and saying, "You're the son of the Dean of Engineering?" I'd say, "Nah." It never bothered me anywhere along the line. I never had any problems one way or the other with that. I think it helped me once in a while. In graduate school, they knew who I was, so I wasn't just another person coming in, but from what they thought I had no idea, so nothing got reflected to me at all.

Hochheiser:

Which is of course all I can ask.

Terman:

Yes. Right.

Hochheiser:

So pretty much in your mind you had switched from physics to electrical engineering while you were still completing your physics degree.

Terman:

Yes. Right.

Hochheiser:

Did you consider any other graduate schools other than Stanford at that point, or did it just seem natural to stay?

Terman:

It seemed natural to stay because Stanford was very good in electronics. One of the things that I was very interested in was the transistor and Stanford was getting a going effort in transistors and semiconductor technology from some people who had come from Bell Laboratories. So that seemed to be natural. I was changing departments, and why go off to some new university? Yes. Part of the maturing process going to another university is fine for people who need that maturing process. I didn't feel I needed it. Stanford had a good group of people, and I was interested in the kind of work that they were now beginning to focus on, so it seemed reasonable to stay at Stanford.

Hochheiser:

What was the graduate course work in electrical engineering like while you were there?

Terman:

Good question. There was an introduction to semiconductors, introductioto semiconductor circuits. As it turned out, because semiconductors in the transistor business was coming in, I took the introduction to semiconductor device physics and the energy bands and all that five times. By about the third time I had it down pretty well. The circuits were kind of interesting. There were a whole bunch of circuits. Much of the circuitry was close to what the tubes were doing, but it was a bipolar device and there were some changes. With the bipolar device the input was a base, which was not high impedance whereas with tube the grid input was high impedance. The grid was much more like the MOS device, which is kind of interesting because it is what I ended up going into.

Terman:

There were some differences in the circuits, but fundamentally you put a load device up and had characteristics and you worked with the characteristics. Nowadays it would look pretty primitive. There were some differences. There was a very good professor, Malcolm McWhorter, who really knew circuits. He was wonderful. I loved his tests, because at the test you look at this and say, "Oh, this is a new circuit, a new something, a new function that I have never seen before and I'm going to have to work this through in the next 15 minutes," but it was really interesting because he gave you tests that sort of stretched you. It wasn't like "regurgitate what I've told you." But rather, "okay, I've told you stuff, now apply it." He and some of the other professors were pretty good at that. That was a real challenge and really good I think.

Hochheiser:

How did you choose your thesis topic?

Terman:

Ah Yes. There is an interesting story on that. It's being at the right place at the right time. There is a preamble for this. Gerald Pearson, who was the inventor of the solar cell, I guess the co- inventor of the solar cell, came to Stanford for six months. My thesis advisor had been Joe Pettit [Joseph Mayo Pettit], but he left. He became Dean of Engineering and left for Georgia Tech, so I didn't really have anything to do. He was a circuits person by the way. Then Gerald Pearson came in and said, "Nobody has ever measured the spectral response of solar cells – the change in the frequency of the light that goes in – and seen what the solar cell response is. So why don't you do that?" I said, "That sounds pretty interesting."

We were married so it was 1958, my second year. I went and did this, and we made solar cells in our own small diffusion furnaces and so forth. But Pearson went back. I finished that and I did a simple theory of how it would work, explained the characteristics, and published that paper – which at that time was very unusual. People did not usually publish before they graduated. I had that experience. Pearson had gone back, and John Moll had arrived from Bell Laboratories.

Terman:

I got to know him through working with Pearson and that group. One day I had gone back to the circuits group and was sort of feeling around. I was not really finding anything that looked interesting. One day I was walking west, and Moll was walking east. He said, "I've got a good thought for a thesis topic." I said, "Okay. What is it?" Then he explained the MOS capacitor and the thing that would be measured there. I said, "That sounds good, but I have sort of signed up with this guy over in the circuits department," and Moll said, "I'll talk to him, no problem." Moll, from Bell Laboratories, had taken some work that was done in a much different version, but the same sort of thing, by some people at Bell Laboratories. In the MOS capacitor it was measuring the surface states at the MOS device, which became the MOS n-fet or p-fet. It turned out to be something very valuable. It was an ideal thesis topic because there was a theoretical curve and an actual curve, and the difference was the surface states.

The surface states were totally unreproducible. Nobody could say you’re your measurements were wrong as long as the one that had surface states was above the one with the theoretical curve. You couldn't be wrong. I remember guys designing circuits, fabricating them, measuring them, trying to go figure out why they didn't match. I had no problem. It was surface states. What was interesting about that was that, first, the surface states became very important; and secondly, I went through and measured this and came up with a complex impedance structure or equation, a representation. Then I worked that back to where the surface states were – the actual physical location of the density. It turned out there were just two major energy levels of surface states.

It was really interesting because – and actually you could go back into it and say, "I measured this" and I'd go back and actually see what is going on in the physics of the device. It turned out they were representative of what people were trying to get rid of as this developed into the MOS device later on. It was a bit of luck or just being at the right time and having Moll there. It worked out beautifully. It was a great thesis. I think there were close to 300 reprint requests over the next three or four years, which in those days was a tremendous number.

Hochheiser:

I believe you first joined the IRE while you were in graduate school?

Terman:

Yes. In 1958 Dad said, "You should join this group that I have been President of," and I said, "Okay." It cost no more than five dollars, and he was paying me anyway, so no problem. There was no student chapter. There was no activity whatsoever. I got the Proceedings, and that was about it.

Hochheiser:

There was no student branch at Stanford?

Terman:

Not that I know of. No, there was nothing. I joined and I got Proceedings, which was nice. I also subscribed to the McGraw-Hill Electronics. Proceedings was high level; Electronics was good and very useful.

Hochheiser:

You finished your dissertation.

Terman:

Yes.

IBM

Hochheiser:

What led you from Stanford to IBM rather than some other opportunity?

Terman:

Bobbie and I had met and gotten married in 1958. She had been to Northwestern [University] and I had been in the east in Boston for three years during the Second World War, so we had a little touch of that.

We were interviewed at Fairchild by Gordon Moore, [Robert] Noyce, and [Jean] Hoerni. That was a pretty good group to be interviewed by. We talked to HP [Hewlett-Packard]. John Atalla was there, and John Moll of course was at least consulting at that time. We went back to IBM because a fellow named Ed Davis who had been at Stanford and had gone to IBM. He and a gentleman named Rex Rice came back to Stanford on a recruiting trip. Rex was one of these guys who could sell refrigerators to Eskimos – a very interesting guy, and Davis was also a really good guy. They said, "Hey, you've got to come back." I also knew some people who had gone to Philco-Ford in Philadelphia, so we made a trip to go there. We also went to TI [Texas Instruments]. We did the two local ones and then we did the trip back there. I ruled out Philco-Ford because it wasn't clear to me that they were going to go in the long-range direction. I didn't go to Bell Labs because I had a brother there and it didn't sound like the right place to go. Then I went to IBM to talk to people. The two people who were working in my field, John Marinace and Dick Rutz in the device physics field weren't there at the time. Rex made his pitch to me. It was really good. The people up in Fishkill area in bipolar devices and technology made their pitch and that was pretty good, too.

I came back and we decided, let’s go spend a little time in the east and then we’ll come back to the west coast and work for Hewlett-Packard, which is the obvious thing to do. Fairchild didn't seem to quite fit right even though there were some good people there, as we’ve found out. We decided to make the arrangements to go back and make the final decision when we got there. It was a matter that IBM looked good. They had good technology going on, some very interesting stuff. Rex was doing some stuff on computers that looked interesting. It was a big company, a growing company, and just the chance of going back east and having a little chance to sort of move away from where we were and then perhaps come back was appealing. I went back to IBM and stayed there for forty-five years and one day.

Hochheiser:

Did you ever consider an academic career? That is the other thing one can do with a Ph.D. in EE.

Terman:

I liked the idea of doing things, making it, and making it happen. Moll said, "You probably are the right person for going to a company and producing things." Moll was a pretty good guy and I thought he had a pretty good insight. That just attracted me. I'm going to go and do something, and I'll have it. I ended up at the Research Center, which was great. I could do things, I could publish stuff, and I had the freedom to go off and do my own things and go in my own direction. It just seemed like that was a good place to be.

I thought about it. About ten years in I said, "Maybe I should start looking at going into academics," but the Research Center always was a very good place to work, and you didn't have to go around with a tin cup asking for money. You could tell the person you were reporting to, "I want to work on this," and 90 percent of the time they'd say, "That's good." Occasionally programs got cut off for one reason or another. Then you'd go off to something else.

In the Research Division when I got there, there was everybody. You had physicists, mathematicians, chemists, circuits people, technology people – all this range – and they would bounce back and forth. You could interact with people. I remember one time we were working on something on error correcting codes, and I needed some mathematical stuff. Down at the end of the hall was a mathematician who had worked in statistics and probability theory. That was terrific. You had this opportunity to go out and talk to people and fill in what we didn't know, and you know they could teach you or they would tell us where to go to learn. It was a good place to work.

Hochheiser:

When you finished your degree and moved to IBM you transitioned from being a student member of the IRE to being a regular member of the IRE.

Terman:

Yes. The cost didn't go up that much, unlike nowadays. However, there still was no local group of IRE, which became IEEE later on. When they changed the name, I was annoyed. They had just changed over from cycles per second to hertz, with which I had real problems getting comfortable with. Then they changed the name from IRE to IEEE. It doesn't make sense. Why did they do that? Obviously in retrospect it was the right thing to do. It was really a very smart move, but I didn't appreciate it.

I was sitting there in Yorktown Heights, and I found out there were some meetings being held in New Jersey where people got together, including Bell Labs people and IBM people. I started going down to those meetings. It was about an hour's drive to get down there.

Hochheiser:

Would this have been not long after you arrived there?

Terman:

Yes. This was probably about 1963. I had gone through my magnetics memory phase and was doing some studying on the semiconductor memory also on the semiconductor technology.

Hochheiser:

Was that your first involvement?

Terman:

Yes.

Hochheiser:

Were there several of you from IBM who went down to New Jersey for these meetings?

Terman:

Not that many from the Research Division because there weren't that many people doing circuits per se. There were some technology people, and we'd meet them. I'd meet some people from Fishkill that would come down. It was not said "This is an IEEE function." It was, "There is going to be a meeting on semiconductor such-and-such and we're going to do that. Are you interested?" I was on the mailing list. It was mailing at that time.

Hochheiser:

Sure.

Terman:

I would find out and then drive down. It was interesting because I met people that I would not have met otherwise both inside and outside of IBM.

Early IEEE involvement

Hochheiser:

This was a meeting of an IEEE group?

Terman:

I believe it was IEEE, yes. It almost certainly was, but I don't remember them saying, "Welcome to the IEEE meeting." I probably wouldn't pay that much attention to it either.

Hochheiser:

Do you recall discussing the transition from IRE to IEEE with your father?

Terman:

No. It just happened one day. I got the newsletter or whatever it was that said, "We have merged and changed the name," and I said, "Oh great. Now I've got to remember another thing."

Hochheiser:

Beyond these meetings in New Jersey, what was your first involvement with IEEE – papers, conferences, whatever?

Terman:

My first two papers were in Solid-State Electronics, which is a competing journal. It's still around, I believe. Don Pederson, who was a professor at Berkeley and a friend of my father's, suggested that I should join the 4.10 Circuits Committee of the IEEE. That was a subcommittee of the Solid-State Circuits Council. He was a past president of it. That was an actual circuits-focused group. I had been going to the International Solid-State Circuits Conference every year, which was held in Philadelphia at the time, so I started getting to know various people at the conference and the circuits people.

Hochheiser:

Was this an IEEE-sponsored conference?

Terman:

Yes. It was IEEE. The Council and IEEE and the Philadelphia Section did it. Pederson said, "You should join this. The first meeting is on Sanibel Island in July." Sanibel Island is on the gulf side of Florida.

We had a room where the air conditioner worked, but some people had rooms where the air conditioners didn't work. It was pretty friendly, and it was interesting. Here’s a bunch of people meeting and talking about circuits. It was over my head in a lot of cases, but the MOS was beginning to come up and I was pretty much into that. It worked out quite well. That was quite interesting. I attended two DRCs, Device Research Conferences in 1961 and 1962 because I was in devices somewhat. There was one held at Stanford when I came back to get my diploma and then the next year it was in Maine, so I went to that. But then the Solid-State Circuits Conference was where I was going, and then Pederson said, "Hey, you should join this committee." That was really my first step in, because I became part of this committee and eventually became chair of that committee.

We would hold meetings down at the old United Engineering Center in New York where IEEE had three floors. We'd have a technical meeting. That was a time when people would literally fly across the country for a one-day meeting. They wanted this interaction with people who were doing things. So, you could get people from this local area, which had Bell Laboratories and a number of people out of Long Island as well as IBM and so forth, but we also would get people from TI, Philco-Ford, and Fairchild-Intel who would come to this one-day meeting. We could get maybe twenty or thirty people there with four or five speakers and actually have a sort of one-day symposium. This was really, really important I think for the development of the technology. People could talk about things before they were ready to give a paper at a major conference

Hochheiser:

I find it interesting that the meeting was held at the United Engineering Center, basically at IEEE headquarters.

Terman:

Yes. They had a couple rooms. We would go ahead and reserve it and then tell people. And I guess people wanted to come to New York. That may have been good.

Hochheiser:

Yes. Why was it called the 410 Committee?

Terman:

I suppose there was a 4.9 Committee. Four point one zero [4.10]. I don't know. It was just how they parsed out the organization at the time.

Hochheiser:

You eventually became the chair of the committee?

Terman:

Yes.

Hochheiser:

What did being the chair of the committee involve?

Terman:

Making sure we had meetings. We would have a one-day meeting generally at the International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISCCC), a one-day or few-hour meeting where people would get together and say, "What are we going to do?" People would say, "This is a good topic" and say, "yes, that's good" or "maybe not" or "could you slant it this way?" We would get five or six people together working on meetings. I would say we had an 80 percent success rate in getting the meetings together. It was pretty good. People who were working on semiconductor memory would have a meeting on semiconductor memory. People who wanted to talk about designing microprocessors when Intel was the only people who did it, we'd get people together and talk about how they were designing processors. It was really good, because you had a chance to do things not in front of hundreds or thousands of people, which you would have at a conference. One also had to get over the bar in order to get into the conference.

Hochheiser:

Did your being chair of the 4.10 committee lead to larger things?

Terman:

Yes. Dave Hodges [David Albert Hodges (1937-2022)] had been the previous chair. He moved on to become editor of the Journal of Solid-State Circuits. Jim Meindl [James Donald Meindl (4 April 1933 - 7 June 2020)] had been the first editor and Dave was the second. Jim Meindl had been editor for five years. Dave suggested that I be an editor of the special issue the Journal of Solid-State Circuits. They actually did two issues from the Solid-State Circuits Conference – one on digital circuits and one on analog circuits. I was the guest editor of that issue, and it went very well. I was the guest editor of the next year's issue also. He asked me if I would like to do it again, and I said “sure.” Then he said, "Would you like to be an associate editor?" I said, "That's fine" because I’d been a guest editor. Then I went on to be the editor of the journal.

They also said, "The editor of the journal really ought to be part of the Solid-State Circuit Conference Program Committee," so I got into that group. It was sort of building here. One does one thing and does it well and then starts doing more things. Being associate editor and then editor of the Journal of Solid-State Circuits I would go to the Administrative Committee (AdCom) meetings of the Solid-State Circuits Council, so I got to be known there.

This all sort of just snowballed. I wasn't making any real intention. It was just, "Oh gee, this is interesting. This is the next step up." And yes, being editor of the journal there are some good things to be done here and I could have some more impact. You also have people I thought would make good associate editors and guest editors.

Journal editing, Solid-State Circuits Society

Hochheiser:

What does one do as the editor of a journal?

Terman:

This was before online submissions. People would send the articles in, and I would look at them and say, "Hmm. This should go to associate editor number one, two, three, four, five." I of course would pick the associate editors, and I would get rid of them when they had gone through a three, four or five-year term, whatever was appropriate, and get somebody new, particularly if fields started changing. Being involved with the conference I knew who were good people, the new fields, and what people that were respectable there in different areas.

At that time, you took the articles in and sent them out to the associate editors. They would make the decision to accept or reject, although there were some ones that I did myself. I was at IBM. IBM had a big Josephson junction effort for Josephson junction logic, which is cryogenic logic. I did that myself because I knew the people. There were only three people to do the reviews. There was one in Yorktown, one in Zurich at IBM, and then one guy in the University of Minnesota, so I would handle that. Sometimes they didn't agree. It was kind of interesting. Most of the time they did. You could do some of that yourself, but it was getting the journal going.

We had the guest special issues from ISSCC, but a European Circuits Conference started, and I went out and got a guest issue for the journal from the European Solid-State Circuits Conference, which I think was important. We also had a special issue on technology shortly after I started. We were a pretty good place to have a discussion of technology appropriate to circuits. But then it got more … and that issue got dropped. On the other hand, the Electron Devices Society showed no interest whatsoever of having a special issue from their flagship conference, the International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) on technology, which I found kind of interesting. A different way of doing things.

Hochheiser:

The journal you edited was sponsored by the Solid-State Circuits Council.

Terman:

Correct.

Hochheiser:

What did that mean, Solid-State Circuits Council?

Terman:

Oh, the council at IEEE. We have Societies. If you have a technology that covers a number of technical fields, the technical fields of a number of Societies, you can make a Council. An example is with circuits. Circuits was used in almost everything. We now have an Electronic Design Automation Council. That is used in a whole range of things. You would think we would have a Computer Council. We don't have a Computer Council because we have a Computer Society. The Council basically covers multiple technical fields of more than one Society. It does not have members. Whereas a Society has dues-paying members, the Council does not have members. It has on the Board people that are appointed by the specific Societies that are supporting a particular Council. Beyond that it is very much like a Society. It just doesn't have members.

Hochheiser:

In practice, what if any difference, does it make?

Terman:

For a long time, it didn't have chapters. I argued when I was president that Councils should have chapters and we now have chapters for Councils where it makes sense. Otherwise, it has publications, does conferences, can do educational programs, can have all sorts of levels of interaction with people. It was basically with a technical focus without geographic focus, although now we have chapters, which have the geographic focus.

Hochheiser:

In looking at your official activities record in the IEEE records I noticed that in this period you joined a number of Societies.

Terman:

Yes.

Hochheiser:

You were listed as being a member of the Computer Society, the Electron Devices Society, the Circuit Systems Society, SSIT [Society on the Social Implications of Technology]. Now is this related to your participation in the Council?

Terman:

The Electron Devices Society was because I was working in technology also.

I would go down to the International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM). It's another flagship conference. They are equivalent to ISSCC. I'd get there, I’d fly down there in the afternoon. What did I do before the meeting starts the next day? Well, I would walk into the Electron Devices Society AdCom meeting. I knew a few of the people from these various meetings we had in the New Jersey area. I would just sit down and listen to what was going on. They got to know me, and I was there.

Juri Matisoo, who was my manager at IBM, became the secretary. Urey had trouble getting the minutes done, so he would say, "Would you mind doing the minutes?" So, in fact I was the secretary. I would take his notes on the minutes and write up the minutes. Then they said, "How would you like to be on the AdCom of Electron Devices? You are working the field, you have published papers in the field, and you already know what's going on." I did that, so I was really doing the two of them, which was a natural sort of thing.

Hochheiser:

You were simultaneously active in the Solid-State Circuits Council and the Electron Devices Society?

Terman:

Yes. Now, the Computer Society, computers were important. I was working for IBM. They had a really good magazine, Computer, that still comes out, that is not for computer buffs or dorks, whatever you want to call them. It's for people who are in computers and might be interested in some other part of the computer field. It's not written for the academics or the high-level researcher.

There was a lot of good stuff there that one learned about computers and applications and what they were doing and what they were thinking of and for what.

Circuits and Systems, I was asked to be on the AdCom. I was a circuits person. I was on the AdCom for three years and I guess I still belong to it. There is not a lot of overlap, although it was very interesting when we changed from a Solid-State Circuits Council to a Society. They wanted us to merge in CAS, and the people said, "No. CAS is theoretical people; we are real people. We design real circuits that are actually used." There is a disagreement there. There was actually some conflict dating probably ten years before that, so there are two separate Societies. I think that's the right way, actually, to have it done. [I joined] SSIT because I was always interested in the social applications of what does it really mean, the application of technology and its impact on society.

Hochheiser:

You were editor of the Solid-State Circuits Journal for three or four years?

Terman:

Three years. Yes.

Hochheiser:

What led you to step down at the end of that?

Terman:

It was three years. I felt that was the right time. Dave Hodges had done it for three years. Jim Meindl had done it for five; hats off to Jim Meindl. He started it, by the way. He really did a great job. I had an associate editor, Paul Gray, who was spectacularly good, so I said, "Paul, you should do this." He was at Berkeley and Dave Hodges was at Berkeley. I think they probably talked about this. He said he would do it. Three years is about the right time because if you are doing it all yourself it begins to wear. I was publishing 600 pages. It went up to 800 pages after three years. People are publishing 2,000, 3,000 pages now. Yes, they are getting support, but it's a lot of work and wear and tear, so I said, "This is about the right time to step down."

Hochheiser:

You remained very active in the Council even after stepping down.

Terman:

Right. Yes. It was 1977 when I stepped down.

Electron Devices Society presidency

Hochheiser:

Right. During these years in the 1970s, did you have any awareness or involvement yet in the overall IEEE as opposed to the specific societies?

Terman:

No. The next step was becoming president of the Electron Devices Society. When I became president of the IEEE Electron Device Society I got onto TAB [Technical Activities Board]. I sat there as president-elect of the Electron Devices Society and watched what was going on. There are thirty people sitting in there. There are ten people on the AdCom Board of Governors. It's nice. I knew everybody and "How are things going?" and so on. Then you go on TAB. Craig Casey [H. Craig Casey, Jr.], who was the president before me, said, "You really ought to go up to visit a TAB meeting, but you don't have to do it," so I said, "I'm not going to do it. Too busy." In February, when I was president, I walked into the room.

Hochheiser:

What year was this?

Terman:

This was 1990. Electron Devices Society was 1990. God. How quickly things fly.

Hochheiser:

1990-1991. I am now looking. I wrote it down.

Terman:

Yes. It was [president in] 1990-1991. Yes. What did I do in the 1980s? I don't know. Don't ask. I walked into this room and there was this formal setup and the guy who was the chair of it was up there at a table. I looked around and there were I guess thirty people like you. There were a whole bunch of other hangers-on. Suddenly, I realized I have moved up a big step. This is a different group. They don't know me. There was a chair open. I walked in and sat down next to Jan Brown, who was quite active in a number of IEEE things.

It was a different feel. There were about thirty people who’ve got the same problems you’ve got, except they were different. I’ve got a pretty good thing. I‘ve got conferences that were run pretty well. I’ve got a journal. Other people have journals that are struggling or have conferences that weren't doing too well or have three or four conferences. I only have one that I was worrying about.

It's just a different level. You sit there and kind of hunker down and say, "Okay, I'm going to understand what's going on before I say anything." Then you started saying things. Nobody says, "Boy, that was stupid," or anything like that. You realize that there are other people in the same place you are. Half of the TAB is turned over. In fact, more than half because there are some people who only have one-year terms. Half of the TAB people are on the first year and another group are on their first year because they didn't have a year before. Everybody is in the same boat, I guess. It was quite an experience. Once I got over the shock, I enjoyed it.

Hochheiser:

Do you recall any specific issues or topics that were discussed?

Terman:

Not that much, other than that there were some financial problems. There was a question of how TAB was funded and so forth. IEEE at that time had nowhere near the reserves it has now. There was a downturn in the early 1990s where things were a little bit tough. I think there were questions on conferences, optimizing conferences; there were questions on journals; and there was the typical TAB thing, "TAB is IEEE. We do the conferences, we generate the journals, we are the source of all the information. The rest of you guys should go. Why are we paying for you guys? What's the rest of IEEE doing?" That view has, thankfully, vanished. There was a lack of understanding what MGA [Member and Geographic Activities] did, and what at that time was RAB [Regional Activities Board].

Hochheiser:

RAB, yes.

Terman:

No appreciation of EAB [Educational Activities Board]. No real standards activity. I'm not sure that IEEE-USA existed at that time. Something like IEEE-USA. Professional activities. But yes, TAB had this paranoia, "We do it all and the rest of you guys are just hangers-on. How do we get you to understand this?" As time went by, I think, it has gotten corrected dramatically since then.

Hochheiser:

You were on TAB because you were a Society president.

Terman:

I was at the time president of Electron Devices Society. Yes.

Hochheiser:

Can you tell me about being president of the Electron Devices Society? What did you do as president? What issues did you have to deal with?

Terman:

Yes. Electron Devices had good going conferences. DRC, the Device Research Conference, which was an academics-oriented conference, was held at universities in June. People would come in and give their discussions. Papers weren't necessarily final. I remember the second year when I went to the DRC in 1962 there was a discussion about a paper and somebody talked to somebody who had given a paper the year before and said, "But in your paper it didn't agree with this." The guy said, "No, I'd like to apologize for that paper." Now that was a great attitude. Secondly, the fact that he didn't hide was terrific. Third, these things were down to where you could make a mistake and people would say, "Okay, I understand" and somebody else would come on and presumably followed some of the work and some of the leads that he had. That worked out pretty well. We had good conferences. Actually, at that time I think we had about fifty conferences we were doing, so we had a good source of revenue that way. We had the Electron Device Transactions, which is a major journal, and we had I believe just started the Electron Device Letters, which had a fast turnaround time. Miraculous; a three-week to one-month turnaround time. We were doing that, getting comfortable with that, looking to expand into extra conferences and so forth because this is when Japan, and to some extent a little later Taiwan, was coming onboard. There was a lot of work going on there. How do we work these people in? It was a matter of keeping what already had good momentum going. When I became president the first thing, literally almost the first thing, we did was to look for an executive director for the Electron Devices Society.

Hochheiser:

There wasn't one when before?

Terman:

Correct.

Hochheiser:

Was there a vacancy or was this a new position?

Terman:

We said, "It's getting big enough; we'd better have this."

Hochheiser:

Now we want to have an executive director.

Terman:

We'd better have one. Yes.

Hochheiser:

That's a big step for a Society to take.

Terman:

That is.

Hochheiser:

"We're big enough now; we need this kind of full-time high-level staff support."

Terman:

Yes. "And we're going to spend you know a hundred thousandish, give or take 20 percent, for this person." Big economic impact also. They went through and came up with four people, two inside and two outside. We went down for a day – myself, Craig Casey, I think Dexter Johnston, and Mike Adler. The four of us interviewed people. The first guy was pretty good, the second guy was pretty good, the third guy was so-so, [and] by the fourth guy we were tired. "Hey, we had some good people this morning," and the fourth guy was coming in, so we said, "We'll talk to this guy and make our decision." The fourth guy was Bill Van Der Vort.

I get choked up on this because Bill was perfect. He was ideal. He got the two staff awards, and he was just the soul of the staff for fifteen years until he retired a couple years ago. He was just the perfect guy. We just looked at each other and said, "He's the right guy," so we got him. I felt really good. Bill stepped into the job, ran with it, and became one of the top staff people, an outstanding executive director. I don't know that many executive directors. I had one other who also turned out to be outstanding. We'll get into that in a minute, I assume. But he was good. When he needed it, he hired staff. He hired Laura Riello to work with him, and she was very good. She's still there. Then he hired other staff people. I have never heard anything negative about the staff. They're really good. It started out well.

Hochheiser:

How closely did you work with Bill once he was hired?

Terman:

He contends that I taught him everything he knows. I contend he hit the ground running. We talked, but he was really good. Yes, I probably helped him out by telling him how things were going and so forth. We had a lot of interaction, but I think Bill was a natural and really knew where it was going. He wasn’t the only ED [executive director], he was smart enough to talk to other EDs to find out what was happening. Electron Devices was a kind of unique setup, and a unique organization, because it had so many conferences that it was doing.

Hochheiser:

You hired an executive director, so this was the first that Electron Devices had a dedicated full-time executive director.

Terman:

Yes.

Hochheiser:

How did having that kind of support change the Electron Devices Society?

Terman:

It meant there was a lot less that the volunteers had to do. They could handle things. All this stuff of pulling together the conferences, Mike Adler was the conference person. He was really good. I mean Mike was one of the reasons the conference became so good for EDS, but now the paperwork didn't have to be done by a volunteer. Bill could do that. That was a big step because it made life a lot easier. For the paper submissions for the journals, that was still done by those people. I think the editor directly sent articles off to the publications people.

As president, I didn't have to set up the AdCom meetings. Bill did that. Setting up an AdCom meeting isn't a big thing, but if you have a full-time job and you're doing other things, it's the kind of thing it's really nice to say, "Bill, okay, the AdCom meeting is going to be at such-and-such a place. Can you set it up, get the contracts written and so forth and send out the announcements to people." All these details are not perhaps difficult per se, but they take time. He did them very well. He was very well organized. They can be difficult if you don't do it right, as you know. It just smoothed things out for the volunteers a lot.

Hochheiser:

If I can step back a bit.

Terman:

Okay.

IEEE Fellow advancement

Hochheiser:

Another piece of your IEEE involvement was that you became a Fellow way back in the 1970s.

Terman:

Yes.

Hochheiser:

Can you tell me anything about your selection and what it meant?

Terman:

Yes. That was terrific. I was surprised. I was at the age of thirty-nine. There have been other people who did it earlier, but it was pretty early. It started because people in the Research Division, one of their things was to get recognition of their people. As a research person you are supposed to publish papers, become an expert in the field, and get recognized. They said, "We're going to nominate you for IEEE Fellow." I said, "That's terrific." They said, "Can you give us a CV?"

They probably didn't know about the MOS capacitor. That work was historic. In the semiconductor memory business, I had given a couple of papers on the magnetic memory. I had been leading in the semiconductor memory. Going from the magnetic memory to semiconductor memory was a very nice step in the Research Division where I had actually had the flexibility to say, "Magnetics, forget it. No magnetic film. This is something where there is a possibility." But we didn't. We had integrated circuits, but they didn't yield. I was saying, "Sometime in the future five or ten years from now we are going to be able to make integrated circuits that you are going to be able to put a lot of circuits on it and they are going to yield and they will be low enough cost." There was a problem within IBM about the core memories because they weren't extendable in speed. I could see that semiconductor memories were going to be able to be extendable, and that to get the density you had to have the MOS device. We went into what was then a totally new area of looking at the MOS device and seeing what you could do, in making memory. Working through that it came out that, we came up with the further unique approach to MOS memory, which did not involve the DRAM – the one-device cell that was the major device cell in the 1970s, it involved the six-transistor cell.

We actually rediscovered the six-transistor cell and did a project. It just turned out that the end of the core memory era was very visible. And so three things came together--The MOS memory work that we were doing, the n- channel technology that was being developed in IBM Research--everybody was doing p- channel and we were doing n channel, which was a much better device but also much harder to make, and the need for a high-speed memory. Those came together around about 1967. IBM had an official program saying, "We are going to see what we can do," and I was part of that program with the circuit approach that I had worked out to give you the speed. MOS was very slow. I had a particular approach that was not extendable beyond what we were doing, but it fit what was needed at the time by IBM. So, we used that approach.

The n channel device came through. They actually managed to control the characteristics. We made these things and it worked. I think it was 1971 when the first semiconductor memories came out where you had a major system with a major side of MOS memory. At that time IBM was it. If IBM did it, that was the sign that it was possible.

Now the one-transistor cell was much more dense and that came over with a memory hierarchy, but we sort of filled in that gap very nicely. That was there. And I had done some other work and some publications. They put me in for the class of 1975. This was done in 1974. Lo and behold it came through. Hurray. I was really very pleased, and a bit surprised. I thought that was kind of young.

TAB

Hochheiser:

Yes. Now getting back to the main story, your term as President of the Electron Devices Society ended in 1991.

Terman:

Yes.

Hochheiser:

Did you stay on TAB after that?

Terman:

In 1990, I had been asked if I wanted to be part of the Society Review Committee, which is a committee that evaluates.

Hochheiser:

A committee of TAB?

Terman:

It's a committee of TAB that reviews each of the TAB Societies and Councils. That was actually a very important thing. They weren't doing it, and they were saying, "Every five years we are going to review these organizations to see if they are going in the right direction and what they are doing and so forth." It was very important for the Societies and Councils because it forced them to look at themselves. Boy, that was interesting. Larry Anderson of Bell Labs was doing it and he finished up his first round I think in 1993 and he asked me to be chair.

Hochheiser:

You were on the committee first?

Terman:

I was off TAB per se, but I was on a TAB committee. I'm not sure of this. I was still going to the TAB meetings, I guess because the Society Review Committee met when TAB met. We were beginning to arrange how we were going to do this, because this was really the first time we said, "Okay. We've got five years. How are we going to schedule all of these things and put this on a firmer basis?" There was a meeting out in California where some TAB people got together. It was some part of TAB. I don't think it was all of TAB. There was a problem. We were having some financial problems within the TAB structure, and the treasurer at the time gave us a pitch about what was going on and what needed to be done. He didn't give good talks, so we came back from that meeting. At the next TAB meeting he gave his pitch and Bruce Eisenstein was the president.

Hochheiser:

Head of TAB?

Terman:

Head of TAB, chair of TAB.

Hochheiser:

Vice president?

Terman:

VP of TAB. Yes

Eisenstein said to me, "I've got to remove the treasurer." I said, "No. This guy is good. Help him with his presentations." He said, "No. He's lost the confidence of TAB." So, he asked me to be treasurer, and I became treasurer.

Hochheiser:

In about 1995?

Terman:

I think it was 1993 or so. I'll look it up.

Hochheiser:

That's okay. Dates are things you can look up.

Terman:

Yes. I think I had a year and a half as TAB treasurer, and then they took me on a second term as TAB treasurer for two years, so it was three and a half years. These major problems with the money came out. We established the TAB support line, which gave us in the TAB budget, "This is what it's costing you to support the TAB department." As it turned out later on, if money has to go to support corporate, that also is in that line.

Then there were big arguments about how to apportion the money among the various TAB Societies – is it by number of members, by their gross incomes, their net incomes, whatever, and so on. It was a pretty interesting time.

END OF TAPE 1; BEGINNING OF TAPE 2

Hochheiser:

You were telling me about being the treasurer of TAB and figuring out how to allocate the operations.

Terman:

Yes. After a couple of years, because the reserves of TAB went up, the TAB support line became a TAB donation line where it went back to the people. That happened twice, once under me and once under Mike Masten [Michael K. Masten], who was my successor, and never again will that happen.

It was a good time. I was involved with TAB and got a pretty good understanding of what was going on. Because TAB treasurer is in the FinCom [IEEE Finance Committee] of IEEE, I got to know more people. Again, this snowballing continued.

Hochheiser:

Now you were on another overall IEEE—

Terman:

Yes. At a higher level. I met Dick Schwartz [Richard D. Schwartz, IEEE CFO, 1993-2010], and we discussed phantom reserves. Maybe I didn't mention that in the CHM tape. With phantom reserves, everybody thinks they have a certain amount of money, including corporate at that time. Now if corporate reserves go negative, or any of the others, somebody else’s money has got to make up the negative corporate reserves. So, you had a slide of this. Phantom reserves, these are reserves where IEEE as a whole does not have much money as the sum of what the individual people think they have, assuming that somebody has gone negative, and you don't count them. That means I, as the Solid-State Circuits Society for instance, some of my reserves has to go to make up corporate reserves. Later on, we hit that. I just happened to be on the Board when that hit.

We realized that the corporate reserves were not going to last forever. At that time, the reserves were going up enough that the corporate was not dropping, not going down badly, but we realized that somewhere along the line corporate reserves were going to vanish and the financial structure of IEEE would have to change when that happened. That was one of the things that happened. Otherwise, it was pretty much looking at how the numbers were going, seeing how the reserves ... There was no discussion of the reserve allocation, which became a rather important point later on in the early zeros.

Hochheiser:

Right. We'll get to that. According to the records I looked at, you were also on the TAB Strategic Planning and Review Committee?

Terman:

Ah yes. Okay, you may want to cut this out, but it was a joke, Strategic Planning. People would get together for two days. They would say, "What do we want to do?" They would come up with what we know as operational goals. Maybe it wasn't quite that bad, but these were sort of things we wanted to do. We wanted to increase revenue. We wanted to have more members. We wanted to increase our education. Whatever. We came up with a whole bunch of these things, and they would assign them to various people to do. Then they would come back a year or two later and see what had happened. It was not, Where are we going? What are we? Where do we want to be in five years? What is going to keep us from being there in five years, ten years?

Basically, the IEEE environment at that time was pretty stable. We did have competition out there. The technical fields were growing, but not anywhere nearly as dramatically as now. You came in, joined IEEE, you got the journals dirt cheap, so there was a lot of reason for joining. We didn't have IEL. We were not competing with ourselves. We had our milieu that we worked in. We tried to improve what we were doing, but it we weren't really thinking very far out. Then all of a sudden, things changed, and it wasn't very good. Nobody said, "Well, we want membership to increase by 10 percent in the next three years." They said, "We want to increase membership." Maybe somebody had a number, but no one said, "Well, if we don't increase membership by 10 percent in three years, we’re going to find out what happened or heads are going to roll." No heads rolled of course, but something is going to happen. It was not very good, and nowhere near what we tried to do in this past decade.

I was there, it was interesting and again I met people who were presidents and of higher levels. I chanced to see how IEEE was put together and was operating. It was a continued step up. You join IEEE, you start going to series of meetings and conferences, and you get involved and things are going. Going through that path is the same kind of thing you do in your job as you move up into different levels. Having this path which sort of preceded what was happening in my job you improve your confidence, your ability to interact with people and your ability to ask questions of somebody who is at a higher level. This is really important. IEEE supports you in your careers, but it also enables your career by enabling you to understand how to do things that will be done in your career. This was a very important thing. I didn't think of it that much at the time, but looking back on it, yes, it was really very important.

Solid-States Circuit Council vice-presidency, Solid-State Circuits Society presidency

Hochheiser:

As the 1990s progress you start to become very active in the Solid-States Circuit Council.

Terman:

Yes.

Hochheiser:

You became vice president in 1998.

Terman:

Yes.

Hochheiser:

How did that come about? How does one become vice president of a Council? I know how one becomes vice president of a Society.

Terman:

Okay. The Electron Devices Society is somewhat unusual in that the president is voted in by the AdCom.

Hochheiser:

That is unusual. In most Societies that is an elected office.

Terman:

The council went through, somewhere in the mid part of the 1990s, [considering] should we stay a Council, or should we become a Society? Staying a council, well, we were very successful. We made lots of money, ran good conferences, dada-dada-dada. "Why shouldn't we just keep going?" The other side is, "The people in our field do not have a voice in IEEE. We don't have members. The members don't have a voice." They had a voice through the other Societies that make up the Council, among of which are Electron Devices, Circuits and Systems, Computer and so forth. The question posed was, "Shouldn't we give those people a direct voice rather than an indirect voice?" you could argue, "Do the people who lead the Council really reflect the people or not?"

They approached me. Harry Mussman was the president or chair of the Council at that time. He said, "You have been through TAB. You know TAB. Can you help us to work on this?" I said, "Yes." I had pretty much said, "I think you want to become a Society because you are going to represent a fairly large group." We had about 8,000 subscriptions to the Journal of Solid-State Circuits, which is a pretty good-sized group. That group ought to be there. Also, the people that made up the Council, some of them didn't show up. Some of them didn't really care. Others had other agendas that reflected the agendas of their home groups. They were a pretty good and supportive group in general. I'm not downplaying them that much. But we want people in the governance group who have the best interests of the Society at heart and understand the Society or what would become the Society.

We decided to go ahead and do this, and with Mussman, Charlie Sodini [Charles Sodini], and I think there were a couple of other people, we worked out a constitution, bylaws, and so forth. I guess it was the first year of Bob Swartz's [Robert G. Swartz] tenure as president. That got passed by TAB. I think that was the first Society that had been formed in some time. Maybe it was the first Council to turn into a Society. That was a rather big thing actually.

Hochheiser:

The move from being a Council to being a Society.

Terman:

Yes. From the standpoint of TAB, it didn't make any difference. This person comes in and sits in the seat. But it was still something that was not common, and there actually have not been that many Councils that become Societies in the last two decades of that I know of.

Hochheiser:

Recently we had one go in the opposite direction.

Terman:

Yes. Which is kind of interesting. Okay. Basically, Harry Mussman said, "Would you help us on this?"

Hochheiser:

Right, because you had experience both with the Council and with having been a Society president.

Terman:

Yes, and I had been on TAB, so I knew my way around TAB and how one might go about doing this.

Hochheiser:

Were the members of the Council, by and large, in agreement with this transition?

Terman:

Yes, although the Circuits and Systems Society thought we ought to merge with them. We did have a series of meetings with them. Mike Lightner became president, and when he became president, the opposition vanished. He was quite sensible about this. It's a different group of people and they're different organizations. CAS had gotten their hands on the computer-aided design part, which is a big part of their focus. Then they had this theoretical circuit stuff. We were the practical circuits. There was actually a significant difference.

Hochheiser:

I assume once TAB approved it that then it had to be approved by the Board before it was official.

Terman:

Yes. But once TAB approves it, you don't expect the Board to disagree.

Hochheiser:

You don't expect the Board to disagree?

Terman:

Yes.

Hochheiser:

Was there substantial debate in TAB or did it seem pretty clear-cut?

Terman:

I think there was some discussion, but no, it was pretty straightforward. The question of whether we should have two organizations with the term Circuits in their name came up. We explained why there is a difference and the fact that at that point CAS had no problems with it, so it went through pretty straightforwardly.

Hochheiser:

Now, suddenly, Solid-State Circuits had members.

Terman:

Yes.

Hochheiser:

How many members did you start out with?

Terman:

We said at the Solid-State Circuits Conference, "If you join the Solid-State Circuits Society, it won't cost you anything. You get half a year membership." It was supposed to start in April I think because the renewal is in October. IEEE gave that to us, and we as a Society supported that half year. We ended up with about 8,000. We had 7,900 people subscribing to the journal. Essentially all of them came through and some new people came through. And, all of a sudden, for reasons I do not know and do not understand, the subscriptions to the Journal of Solid-State Circuits started going up to over 10,000. It peaked at 14,000, so that was where our membership was. The journal has always been part of the membership.

We actually attracted members. That was the best example I got of why Councils should become Societies, although I do not understand the thinking that goes on in people's minds why all of a sudden, we almost doubled the subscriptions to the journal. It's a mystery. Then the Society doing the things that it did. We added a bunch of conferences, and the journal has expanded in number of pages rather dramatically.

Hochheiser:

What did you do as president of the new Solid-State Circuits Society?

Terman:

The first thing we did was to hire an executive director.

Hochheiser:

I guess now that they were a Society you needed it.

Terman:

We needed it. We had got a number of things going. Not as much as Electron Devices had, but our financial situation was good. We decided, “Look, we're going to be a Society. Let's do it right. Let's start out with an executive director. We'll probably just have a single person, so it won't be quite as much as Electron Devices. Financially we could afford it, and this was the right thing to do. And we'll make sure that volunteers do what they should do, and we have an executive director to do what they should do.”

We interviewed. It was Anne O'Neill who came in and has been with us ever since. She has been the heart of Solid-State Circuits and has done very well. She has hired one extra person because they don’t have as much to do as EDS. That has worked out very well also. It helped. We could not have developed the magazine without help from Anne and the person that she hired, Katherine Olstein, who has really made the magazine what it is. We had a newsletter, but it was a newsletter, and now it's a real magazine. It's quite good.

Hochheiser:

Another miscellaneous activity I saw on your list is you spent two years in the mid-1990s on the History Committee.

Terman:

Yes, I don't really remember much about that.

Hochheiser:

Since I'm part of the staff support for the History Committee, of course, I had to ask.

Terman:

I don't remember. That's interesting. I have always been somewhat interested in the history, but I have no memories. Nothing comes up on that at all.

Hochheiser:

That in itself says something. In these other things you were very much involved and active and have detailed stories to tell me. You were on the committee, but—

Terman:

Nothing much happened.

Hochheiser:

I guess the next thing is your becoming VP of TAB.

Terman:

Yes. I went through and was the president of the Solid-State Circuits Society.

Hochheiser:

And, of course, and back on TAB in that role.

Terman:

Yes. The next thing was that I looked around and said, "Well, I'm the best person to run now. This is the next step. I've been on twice; I know how this is done." There is that thing called the Board, and it would be sort of interesting to be involved with that, but no, that wasn't the big thing. It looked like it was a good next step to do, so I ran against Gordon Day.

Hochheiser:

Yes. This is a contested election by the members?

Terman:

It was contested by the members. Yes.

Hochheiser:

By the members. Was this a kind of election you had to do any campaigning for?

Terman:

No. I didn't campaign, and I don't think Gordon did. By the way, we should go back in a second.

Hochheiser:

I'm sorry. I skipped something.

Terman:

The president of the Solid-State Circuits Society is also elected by the AdCom. The members of the AdCom are elected by the members. But again, the feeling was that people on the AdCom know who is good and who would make a good president, whereas the members don’t.

Hochheiser:

Right. Again, your election to the presidency of the Solid-State Circuits Society was by a relatively small group of people who all were in a position to know you and be able to personally evaluate you.

Terman:

Yes. Right. Right. Yes.

Hochheiser:

Which if you are getting elected by—

Terman:

The unwashed masses I think is the term.

Hochheiser:

Well, I like to think our members wash at least, but I mean by people who certainly can't personally know you.

TAB Vice-presidency

Terman:

Yes. This is perhaps one of the problems. The Member and Geographic Activities (MGA) Assembly selects their MGA VP. Should the TAB VP or should the MGA VP be selected by the members? You can argue both ways.

Hochheiser:

I'm sure people have.

Terman:

Yes. Because if a small group elects their own president, isn't that a clique? Don't you run into problems? On the other hand, you also run into a problem if it's just done by people who don't know and 20,000 to 40 to 50,000 people vote. How many of them actually know the person? A person could run a really good website and I do okay in the debate and hey, now I’m president. I can say I don't know what people vote for president on. The TAB VP is the same way. For TAB VP, fundamentally at least at that time, the names came out and that was it. You had your little statement, and you had a list of what you've done which was rather constricted in available space. It was a contested election. I got elected, so I was VP-elect for one year.

Hochheiser:

Right. In 2000 and then—

Terman:

Yes. Then in 2001 I was on the Board and that was another step up. I would walk in and see what was happening on the Board. I think Bruce Eisenstein was president at that time. I knew Bruce; that was good. Then we had a really bad downturn in our financial situation, so we spent much of our time looking at that and figuring out how we are going to get out of it. .

Hochheiser:

You were on the Board and TAB. Were both—?

Terman:

On TAB. The Societies and Councils were looking at their reserves. There were three things going on here. One is they were looking at their reserves and the reserves were going down. That's not good. Secondly, the corporate reserves had vanished. We had unfortunately a negative budget for that year. We had to address these problems. We had an actual negative budget. Okay, so the TAB and whoever else had reserves – and it's all Societies and Councils, 90 percent or more – had to pay that negative budget. That was another thing. The third thing was that we put all our money into volatile investments which is great when they go up, because we don't have to pay that until the end of the year and the stocks will have gone up 10 percent by the end of the year so we probably won't lose any money and so on. But when it goes down you have to pay that money no matter what, but you have less money to pay that money. We had those three things going, and all of a sudden people were saying, "We're going to be broke in three years." Looking at the curves, yes, two point form a straight line, yes, we were going to be broke. Plus, people said, "Ah. This is a downturn. Less people will come to my conferences. Therefore, I will not be making as much on my contract, so maybe I will just break even instead of making a reasonable surplus." There was real concern.

Now that is over, and we have matured, and we've got a much better allocation of the reserves – although one of the major problems we had was that we had about three years of downturn. We went from $135 million to $90 million or so in reserves. It was a pretty big downturn. Right at the bottom the committee said, "Wait a minute. We have got to get out of these volatile things, so we are going to go into very conservative stuff." The next five years things went up. I checked on this. I asked the Investment Committee. We lost about $25 to $26 million.

Hochheiser:

By turning conservative at the wrong time?

Terman:

It was exactly at the wrong time.

Hochheiser:

It had not been the right time to do that.

Terman:

When I was president – and we'll get to that, I guess – we rode it out, which is a big, big difference.

Hochheiser:

Of course, when you look at the financial picture, one part is the reserves, but the other part is your income.

Terman:

I don't remember the income dropping that much. There was concern, particularly at conferences. I know some of the conferences did a very good job of cutting expenses so the net, which is what really counts, came out okay. I think the publications were okay because we were starting with IEL [IEEE Electronic Library]. IEL was a great bargain at that time.

Buying publications from IEEE was a bargain compared to going to the commercial publishers outside. But we didn't realize we had this problem with the investment allocation, which was really bad.

Hochheiser:

Did the economic downturn problems leave you time either in TAB or on the big Board for anything else?

Terman:

It was up to the Board pretty much. TAB probably did its usual things of dealing with its internal financial situations, discussions of how the various expenses should be allocated and the revenue streams. IEL was beginning to come in, and I think we were beginning to look at that revenue stream and were asking how we were going to allocate it in different ways. I don't remember great details of what was happening at that time. That was ten years ago.

Hochheiser:

I think just what sticks in your mind, the financial issues, is probably very suggestive about what was happening.

Terman:

Yes.

Hochheiser:

How do you run meetings of a group as large and diverse as TAB?

Terman:

That's pretty straightforward. There is a thing called Robert's Rules.

Hochheiser:

Of course.

Terman:

Robert's Rules, although some people consider it a pain, is in fact good to allow people to discuss. What you do is first you get so that you recognize people. You have a list, so you get them in order. Occasionally, you are not looking in the right direction, so someone might say, "I've had my hand up for ten minutes and you ignored me." Okay, but generally the staff is pretty good at doing that.

You have a list. There are people who will come in from left field and go on and on and so on. You try to cut them off. That's not easy to do, but that's something that you have to do. The Board, or the body, will be pretty happy with that. You like to do that, so you don't get distracted too much. If A and B are on opposite sides and start talking to each other, "Address up here, please. And by the way, don't come in. Your time will come later." You follow Robert's Rules, and you follow what's sensible. Yes, occasionally people will talk back and forth and work something out between them, which might have taken ten minutes of formal discussion to achieve. You also try to limit things and cut things off, but also give everybody a chance to speak. You've just got to do that.

Bob Dent [Robert A. Dent] before me, and I, both had the problem that we'd go through, and we'd be in the middle of the second TAB day and we'd be two and a half hours behind. Somehow, we always got finished on time. Letting people talk and work things out or, "Okay, we've talked today. We're going to talk tomorrow about this. We're going to suspend this discussion until tomorrow. Can you guys get together and work it out and come forward with either a compromise or a uniform agreement?" It's always nice to be able to say, "Robert's Rules says you can't talk anymore," or "You've had your chance and it's this person's turn to speak."

Hochheiser:

Who were the key staff people that supported you as VP? And what did they do?

Terman: